This is pretty much the opposite of what I promised to be

working on – a series of in-depth discussions about my favorite Slasher films –

but perhaps a little digression is just what I need to get back into the swing

(it’s kind of exhausting getting all those screen caps).

I’d like to preface this, however, by making it clear that I

am not a subscriber to or fan of rampant political correctness. I believe that

cartoons, like other forms of popular entertainment and art, should be

criticized based on the merits of what was considered socially acceptable at

the time. If a film, book, or cartoon happens to step out of and beyond

anachronistic mindsets, it should usually be considered an admirable trait, but

I don’t think it’s anywhere close to a necessity. Children’s entertainment is a

particularly interesting cross-section of the pop culture spectrum for me

personally, because children on the whole are usually ahead of their

entertainment, and modern children’s entertainment has grown in broad strokes

of sophistication and quality of content in my brief lifetime.

Also, just like a wikipedia article, this article contains

many of unverified claims.

Television animation, or more specifically action/adventure

animated series, was a boy’s club for most of my childhood. Action/adventure is

traditionally aimed at a male audience, but there were definite residual

effects from centuries of sexism partially to blame for this truth. If we’re not

including theatrical releases or Japanese animation the speed of growth in relation

to sexism is actually, I think, a solid means to judge the general American

public’s open mindedness concerning sex relations. We like to mark the end of

civil rights problems with specific events, but even after the suffrage

movement was deemed successful, and the sexual revolution was deemed over,

television cartoon heroes were still almost exclusively male.

This fact didn’t escape actress/activist Geena Davis, who

semi-recently was quoted as saying:

“Do you remember the kinds of stuff that they made for us,

for kids, in the oldie old days? Let’s see, the first animation, of course, was

Disney’s Minnie Mouse and… Daisy Duck, who didn’t really do much at all, except

ask to go shopping, I think. There were a lot of Hanna-Barbera cartoons — Magilla

Gorilla, Wally Gator, George of the Jungle — virtually no female characters…On

the Looney Tunes website, they list twelve characters, and only one of them is

female, but it’s the great one. It’s the one you all love and remember the

best: Granny. She’s the one who owns Tweety, and she has to leave so that the

story can happen.” (Quoted from Catoonbrew.com)

course, has a point, but also hasn’t been paying attention to children’s

entertainment for at least two decades by my count. Her childhood was a virtual

wasteland for female cartoon characters, as were the majority of the ‘70s and

‘80s. The best I can think of concerning female role models in ‘70s entertainment

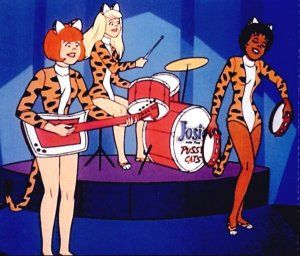

is the sexually unappealing but smart Velma Dinkley, and Josie and her

Pussycats, who were pretty sexually overplayed. In 1984 the United States

Federal Trade Commission deregulated children’s television, and removed most

prohibition against cartoon series linked to toys. In a way this started the

process of homogenizing boy’s and girl’s cartoons. The studios and companies

still aimed their products at specific sexes, but were sure to include a few

female characters in their shows just in case a little sister happened to be

watching.

Because little boys were often stuck playing with their little sisters

characters like Teela (He-Man and the Masters of the Universe), Cover Girl and

Scarlet (G.I. Joe), and Cheetara (Thundercats) were created as backup for their

male counterparts, but none of these characters were necessities to any of

their casts, and were rarely given much to do beyond running in to help with a

team fight. These were strong role models in the physical sense of the word,

but the only things worse than not including female characters at all is

shoehorning them in where they don’t belong, or including them out of duty

rather than interest.

From what I can gather (and I could be wrong) She-Ra: Princess of Power is

the first female protagonist to have her own American made action/adventure

cartoon. Though I suppose arguments could be made for Rainbow Bright and Jem

being adventure series, She-Ra was undeniably more violent, and thusly

‘boyish’. This was an important step, but the show didn’t last too long, and

didn’t have much impact on the rest of the 1980s. Arguably the best long running

show of the period of time stretching from 1986-1991 was The Real Ghostbusters,

which successfully mixed slightly more complex storylines, with a more adult

sense of humor. Still, there was no female Ghostbuster. The closest we got was Janine

Melnitz, the fire-house’s secretary and phone answerer.

The ‘90s were a huge turning point in quality (both in

writing and animation) for television animation, and along with more

sophisticated comedy, drama and characters came better roles for female

characters. Things started awkwardly with characters like April O’Neil who

acted as Lois Lane to the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, but never served any

real narrative purpose, but some of these seemingly shoehorned characters

worked, and early success was found in comedy and (more importantly to this

essay) comic book adaptations.

Between X-Men the Animated Series and Batman the Animated

Series, both of which premiered on the Fox network in 1992, there were dozens

of strong female role models (both in the physical and literal senses). But

there is a difference in the approach of each show, and Batman’s approach is

likely the more enduring one. The X-Men series was largely inspired (story-wise

at least) by the

era comics, which were pretty fair to female characters in the interest of the

comic’s soap opera style. There isn’t a lot of rewriting save the addition of

certain characters, like Jubilee, whose youth serves more importance to the

narrative than her sex.

The Batman writers, on the other hand, took to adapting most

of the comic’s characters for their own means, including some much celebrated

new origin stories for male characters like the Mad Hatter and Mr. Freeze. The

lead female canon creations that were at least partially rewritten include Catwoman/Selina

Kyle, who was re-imagined as a sort of female Batman, with almost as much money

and influence (until she got caught of course), and Poison Ivy/Pamela Isley,

whose new inability to have children developed into a disturbingly Freudian episode

(‘House and Garden’) where she attempts to artificially create a family that is

entirely under her control. Also present was a duo of newly created female

characters, both of which have since found their way into the Batman canon

proper –

the Joker’s right hand girl, Harley Quinn. These two characters became so

popular that many younger fans of the characters have no idea they were part of

the pre-animated universe. Each character serves a radically purpose.

Montoya, who was revealed to be a lesbian in Ed Brubaker’s

‘Gotham Central’ comic series, serves as one of

best cops, and one of the only on-staff supporters of Batman. She’s not one of

the series’ most enduringly memorable characters, but has been picked up by

more adult writers like Brubaker, and had an analog in The Dark Knight motion

picture. Her sex also has almost no bearing on her character. Even her partner,

the largely bigoted Harvey Bullock, never brings up her sexual handicap.

Quinn, on the other hand, is a typically tragic Batman

villain, who is helplessly in love with the Joker despite being a trained

psychiatrist who should know better. Some Geena Davis types may complain about

the abusive nature of the couple’s relationship, and what that relationship

meant to the children watching the show (re-watching the show I’ll admit that

I’m occasionally shocked). But even at 13 years old the tragedy wasn’t lost on

me, so I suspect it wasn’t lost on the other kids watching. The ‘innocent’

nature of the character left the door open to some anti-hero episodes including

one where she teams up with Batman, and a couple where she reveals herself to

be more dangerous to Mr. Jay than he is to her. The enduring popularity of the

character likely has more to do with this ‘innocence’ than her abuse at the

hands of her psychotic boyfriend, or at least I’d like to think so.

Perhaps the biggest step Batman the Animated Series took

concerning the place of women in action/adventure cartoons was the episode

entitled ‘Harley and Ivy’, where the man-dependant Harley Quinn teams up with

uber-feminist Poison Ivy, in semi-homage to Thelma and Louise (which you may

remember co-stared a certain Geena Davis). Besides being the major focus of the

entire episode, the duo almost defeats the Dark Knight. At the end of the

episode they’re finally brought to justice by none other than Renee Montoya.

The episode was successful enough to garner a few ‘sequels’ (part one of

‘Holiday Nights’, ‘Joker’s Millions’ and ‘Girl’s Night Out’).

Look for Part Two soonish.

I’d also like to note how hard it was to find images of these characters that weren’t obscene slash fiction stuff.