Today is the eleventy-first birthday of projected film. Is that experience, the big audience seeing a movie projected on a screen, about to slip on a ring and sneak away from its own party? I don’t think so, but it’s at a crossroads that will determine if it’ll be around for another 111 years.

Today is the eleventy-first birthday of projected film. Is that experience, the big audience seeing a movie projected on a screen, about to slip on a ring and sneak away from its own party? I don’t think so, but it’s at a crossroads that will determine if it’ll be around for another 111 years.

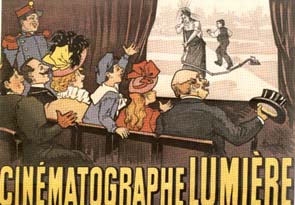

On December 28, 1895, the Lumière Brothers screened ten shorts at the Salon Indien du Grand Café in Paris. They had projected films in private as early as March of that year, but the audience at the Grand Café was the first in the world to pay to see a movie. Other, more technically important moments and innovations would come later, but the basic magic of the movies first happened there. That magic wasn’t capturing the images or using light to display them again – it was the group of people, gathered in the dark, experiencing it together. People had sat together in the dark together before, but plays and concerts were not the same as cinema. When you’re watching a live performance the thrill is being there in the theater with the performers; when you’re watching a movie the thrill is being taken away from the theater, of being transported en masse to another time and place. There’s electricity in that, a current that leaps through every member of the audience, connecting them and uniting them. When a movie is good (and when the audience is good), every person reacts as one. There’s a joy in laughing at a funny movie, and that joy is multiplied by every single person laughing alongside you. It’s fun to be scared by a movie, but it’s even more fun when everyone in the theater jumps at once.

That magic doesn’t end with the credits – a good audience leaving a good movie takes that magic with them as they talk about what they just saw. I love coming out of the theater in a big group of strangers, all of us excited and exhilarated by the film, and all of us in private conversations that are really small parts of one bigger conversation. The best movies end outside the theater, with discussions on the sidewalk or at a restaurant or a bar. Film is about community, and that’s what the Lumières proved in 1895. Thomas Edison had created the first moving pictures, but his Kinetoscope was a solitary experience – you stood and watched the short loop of film through an eye piece. It was the Lumière genius to take the film out of isolation and make it communal. The Kinetoscope was small and close to you, while film projection was big and slightly distanced. The experience of projected film, as much as future advancements in editing and technology, is what has shaped the direction of the movies as art and entertainment over the past 111 years.

And for most of the past 111 someone or other has prophesied the end of the movies. Doomsayers pointed at every technological advance as the coming killer – talkies will destroy the movies! – but none was as scary as the invention of television. That little box in the living room terrified the purveyors of big movies. Why would people go out and pay when they could be entertained at home for free? In response movies got quite literally bigger, as wider and wider widescreen lenses and film stocks were pushed to highlight the difference between the little screen at home and the huge one at the theater.

It turned out that nobody needed to worry, though. TV didn’t kill the movies, and in later years became an important part of how the movies worked. First studios began making money by selling their films to the few existing TV channels, which needed to fill air time. Then came cable, which devoted whole channels just to movies. Then came home video, which proved that TV wasn’t the enemy, but maybe the savior. All of a sudden there was a new and major way to make a profit on a movie, even if it hadn’t done well in theaters. And those profits only ballooned when DVD was introduced. In one of the savviest moves in recent business history, the studios opted to price DVDs for sale, not for rental (some of you may be too young to remember this, but once upon a time a new movie on VHS tape would cost well over a hundred dollars), and it turned out that people couldn’t buy enough movies for their home collections.

But has TV really been the savior? Or was there a silent, bloodless coup? Did we wake up one day and find that home delivery had won the day? I think so. Right now movie studios pump out more and more films every year because the ancillary markets – cable, in-flight entertainment, DVD sales and rental – demand more and more product. This isn’t exactly a new development, since in my grandparents’ day a trip to the movies included newsreels, cartoons and often two features, so plenty of product had to be cranked out to fill the time. And a lot of that content was terrible (it’s funny how we romanticize the motion picture past because we only remember the good movies. Look at 1939 on IMDB – sure, some of the best movies ever made were released, but so were hordes of sub-par programmers), but it was conceived of and made as movie content. Now studios are churning out product that they mostly intend to end up on our non-widescreen TVs, or on our computers, or maybe even on our iPods. Universal has discovered that they can slap a franchise name on some random straight to video dreck and sell a load of DVDs. And people have become very used to experiencing movies not in theaters but on the secondary market. A recent thread on the CHUD message board – surely as much a place where people who like to go to the movies gather as anywhere else – showed that a lot of our readers only made it to the theater a handful of times this year.

That’s the biggest change, and it’s the subtle one that TV and home video has wrought. In 1939, you had to go to the movies to see a movie. And since there was no TV to show the film later, and since you had no way to take the film home and see it again, you had to make sure you saw it when it came out. The movie might get a revival – Gone With the Wind played for years – but to be safe you needed to make sure you were there when it opened. Plus going to the movies was an activity in itself, regardless of what was playing. I’ve talked to a lot of old timers who would just go on every Saturday afternoon and find out what the movies were when they started. People today would probably consider that unthinkable. After all, it’s the exact opposite of the modern philosophy of “everything on demand.” Hell, even the days of turning on the radio and dealing with whatever stations came in are just about over as satellite and internet radio bring us exactly what we want, when we want it, and to wherever we are.

Every year the on demand world gets more pervasive and more convenient. You don’t even have to be stuck watching movies on a TV – there are a myriad of devices that let you take films on the go with you. At least TV, as much as it shrank and diluted the power of cinema, could still be communal. You could still sit on a couch with someone and get lost in a film together. The four inch portable screens barely accommodate one person, let alone a group (although this never stops people on the subway from trying to look over my shoulder when I’m watching movies on my PSP). It’s a return to the aesthetic of the Kinetoscope.

One of the things that kept TV and movies separate was the level of quality – movies always looked better in a cinema. Now even that isn’t the case, as HDTV prices plummet, and as the big theater chains, looking to save money, skimp on presentation. I saw Eragon at the AMC Empire 25 in Times Square – surely one of THE flagship theatrical locations for the chain – and the bulb wasn’t just dim, making the picture murky, it actually was flickering. As if Eragon wasn’t painful enough. But as I sat there I realized I would get a better picture at home.

I wouldn’t have had to wait long, either. The window between theatrical release and home video release shrinks every year (and that’s not taking piracy into account). Once you waited in excitement for a movie to come to the video store – now it’s about 12 weeks. That’s too long for some people, who are trying to introduce day and date releases, putting movies into theaters, on cable and on DVD on the same day.

Strangely enough, I think that’s exactly what needs to happen to save the communal moviegoing experience. First of all, having movies easily available at home will remove the more annoying elements of the theatrical audience – the people who talk and the people who can’t turn off their cell phones and the people who bring their kids to R-rated movies. For the most part these people don’t really care about the movies, and they’ll just as happily and mindlessly consume them at home.

But most importantly, a day and date system will force theaters to compete with convenience, a very formidable enemy. The audience will never dry up – just because people can see any sports game on TV doesn’t mean the stadiums sit empty. The true lovers will always come out, and the casual fans will still want to get out of their house on a Saturday night. But to make sure that theaters still get enough patronage to make the whole thing fiscally worthwhile, theater owners will have to offer more perks. I don’t think we’ll go back to the newsreels, cartoons and two features format, but I do think that we’ll see more theaters in line with Los Angeles’ ArcLight, which has assigned seating. Or more theaters like Austin’s Alamo Drafthouse, which serves good food. And we’ll see more events like the recent Dreamgirls roadshow, where people paid 25 bucks to see the movie early and without ads, get a nice program and enjoy lobby displays of costumes from the film. Dreamgirls played to packed houses at these roadshows – which were based on a fairly common practice from decades ago. If the theatrical exhibitors don’t step up their game, they’re going to find themselves limping along as people continue to get used to watching movies in more convenient, on demand ways. And while movies won’t end, maybe the magical aspect that makes it worth being fanatical about them will.

I saw Rocky Balboa as a paying member of the public last week. The experience was fantastic. The crowd cheered and clapped throughout, and the energy in the room was palpable. The movie created reactions, and those reactions created more reactions in the crowd – it just kept building. Other people saw Rocky Balboa at home – MGM sent out awards screener DVDs. I imagine that many of the people who saw Rocky Balboa on DVD have nice TVs, and excellent sound systems. They probably have very comfortable couches that are aligned to create the perfect audio-visual experience. But they didn’t have 200 people shouting at the screen when Rocky struggled back to his feet during the climactic fight scene. There’s no substitute for that.