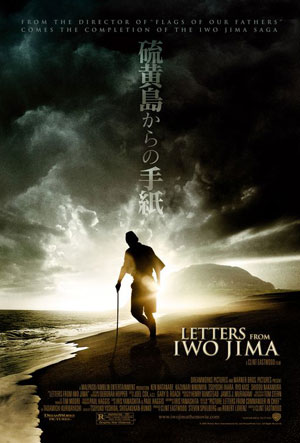

I walked out of Letters From Iwo Jima thinking that we could have saved a lot of American lives in the Pacific Theater of WWII if we had just let the Japanese alone for a bit to kill themselves. Clint Eastwood’s companion piece to the dud-ish Flags of Our Fathers is soaked in suicide, with the Japanese being eager to off themselves seemingly from the very beginning of the battle for a shitty piece of volcanic rock in the middle of the ocean. They seemed so much more cunning and dedicated in Flags, but maybe that’s part of the point.

I walked out of Letters From Iwo Jima thinking that we could have saved a lot of American lives in the Pacific Theater of WWII if we had just let the Japanese alone for a bit to kill themselves. Clint Eastwood’s companion piece to the dud-ish Flags of Our Fathers is soaked in suicide, with the Japanese being eager to off themselves seemingly from the very beginning of the battle for a shitty piece of volcanic rock in the middle of the ocean. They seemed so much more cunning and dedicated in Flags, but maybe that’s part of the point.

Letters is, without a doubt, the better of the two films. First of all, it’s not saddled with a “back home” storyline that doesn’t go anywhere and that just isn’t emotionally relevant to people today. Letters feels very much modern, with its massive Japanese war machine worn down and nothing but doom on the horizon for the empire. Americans can relate to that, more and more. And the structure of Letters is more straightforward – the narrative simply moves forward in time and covers the length of the massive and deadly battle. And Letters is certainly more action packed, and more like a standard war film, than Flags was, making it a more engaging experience.

Eastwood also does something with Letters that is, I suppose, ‘brave’ – he truly presents the story from the Japanese point of view. The flag raising on Mount Suribachi – the main focus of Flags of Our Fathers – gets shrugged off in a quick scene (which, by the way, still feels too obvious. I hate to put Secret Wars in a review for a Clint Eastwood Oscar contender, but that moment reminded me of the terrible Secret Wars II tie-in comics where the Beyonder would be shoe-horned in for one page of a completely unrelated Cloak and Dagger story just so the front cover could tout the book as a crossover.). The American Marines storming the beaches are completely faceless and anonymous. And Eastwood and his screenwriter, Iris Yamashita, have found that standard war movie clichés become fresh when presented from the other point of view, such as a scene where Japanese soldiers find a letter home from a dead American. Hey, they have moms just like we do!

Letters is also grimly beautiful – Eastwood has drained the film of most of the colors, leaving images as stark as the black and rocky beaches of Iwo Jima itself. But grim is really the operative word for this movie; it’s relentlessly grim, almost to the point where it gets redundant and ponderous. Obviously a film like this doesn’t have many interludes for musical numbers, but after a while watching doomed Japanese guys scramble around in caves gets a little dull. Letters never finds a way to build tension, probably because it mostly focuses on two characters, and you know that convention will leave one dead and one alive at the end: Ken Watanabe as General Kuribayashi, who has spent time living in America and is failry Westernized, and the excellent Kazunari Ninomiya as Saigo, a semi-bumbling soldier with a bad attitude who also feels very Westernized. Especially because as everyone else is in a rush to kill themselves, these two characters are the only ones who want to fight on.

Where Flags of Our Fathers celebrated old-fashioned traits like stoicism, loyalty and duty, Letters seems to be going the opposite way – the Japanese who are the leads here are more modernized, throwing off the shackles of medieval feudal thought. And just like with Flags, where the guy who had a different POV than Eastwood’s anointed heroes (in that case it was Jesse Bradford as Rene Gagnon), the Japanese who are not as up to date as the leads get painted with a broad brush of disdain. Rather than try to understand where they’re coming from, Eastwood makes them silly grotesques. Obviously I don’t believe in hugging a hand grenade when defeat is near, but I didn’t gain any insight into the thought process behind it, except that maybe the Japanese committed suicide as a result of cultural peer pressure.

There are extraordinary moments in Letters – I loved the pre-battle scenes on Iwo Jima, and there’s a flashback to one man’s life as a patriotism enforcer that’s essentially worth the price of admission – and in many ways feels like it says in a couple of minutes what Eastwood is trying to say with the rest of the movie’s running time. Truffaut said you can’t make an anti-war film set in war because battle is inherently cinematically exciting; Eastwood seems to have gotten past that hurdle here by setting most of his movie away from the action in dank caves populated by men who are crazed and desperate. Letters From Iwo Jima (the title, by the way, comes from a truly pointless framing device) works better on its own than Flags of Our Fathers, but it’s still overlong and slightly unfocused. As a feat, it’s impressive that Clint Eastwood made these two complementary films. As films, neither of them are as good as they should have been.