George Clooney works a room from the second he walks in. Wearing a t-shirt that covers a back brace (that Syriana injury is still bothering him), Clooney entered my roundtable room at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel like it was filled with old buddies, like it was the one he was waiting for all day.

George Clooney works a room from the second he walks in. Wearing a t-shirt that covers a back brace (that Syriana injury is still bothering him), Clooney entered my roundtable room at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel like it was filled with old buddies, like it was the one he was waiting for all day.

This is the third time I’ve interviewed Clooney and the attitude is always like that. While he has a prickly relationship with the gossip folks, he knows how to play the press. It’s impossible to come out of a George Clooney roundtable not liking the guy.

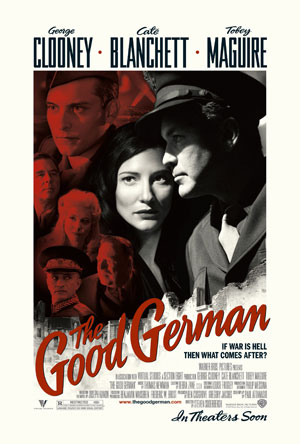

We were there to talk about The Good German, his latest collaboration with Steven Soderbergh, and yet another in the tradition of Solaris – an uncommercial experiment. This time Soderbergh is trying to capture the feel of 1940s cinema, shooting in black and white, using 40s style camera moves and acting. Clooney plays an army journalist coming into Berlin just after the end of the war, covering the Potsdam Conference, which would decide the fate of Europe. While in town he discovers an old flame, a sociopathic driver, and a conspiracy to smuggle Nazi war criminals to safety.

Q: Are you always this excited about working with Steven, or does he have to talk you into something like this?

Clooney: No, we love working together. This is one we developed. We optioned the book and developed the script… and then there’s that awful moment where we have to sit Alan Horn and Jeff Robinov down at Warner Bros. and tell them its black and white. They are really thrilled about that as you can imagine. But, no, every time I get a chance to work with him I’m happy. I’ve never had a bad experience with him.

Q: You seem to be living out the Golden Age of Hollywood in some of your roles lately.

Clooney: Yeah, in a way you do. Here’s the good news or the fun news for me was that for the past few years, we’ve been able to push and do what we wanted to do. And you know as well as I do that that doesn’t last forever, so you try and do things that no one is encouraging you to do. There is nobody at the studio going, ‘Please make a black and white film about the Potsdam conference.’ [Laughs] ‘Give us another black and white about Edward R. Murrow in 1954.’ Or ‘Give us Syriana.’ So we get to push it for awhile and you know they won’t let us do it for much longer, but we’re going to keep doing it for as long as we can. So, for us, it’s an exciting time because we feel like we’ve gotten away with something.

Q: How would you say your relationship with Soderbergh has changed over the past few movies?

Clooney: I wouldn’t say that it really has. I was a fan and stole ideas from him on Out of Sight. And I’m a fan and I steal ideas from him now. Over the years we’ve become very good friends as well and that’s an important part of it – that we’ve been able to spend a lot of time together and that we like each other a lot. But, I don’t get that it’s really changed. I just get the sense that I think the most of him as a director. I’ve been lucky between he and the Coen brothers. I’ve got a couple of people that I really enjoy working with who I also think play at the top of the game.

Q: Do you have a particular affinity for the era of the 40s and 50s?

Clooney: Maybe. I mean, my favorite time, in American cinema especially, is the mid 60s to the mid 70s. I just think that’s – if you look at the films that came out of that generation or that period of time, through all those nuts, it’s just some amazing films.

Steven sent us films to look at for this film, just to talk about, to think about. Some of them I had seen before. Humoresque I had seen before. Mildred Pierce I had seen. I liked John Garfield and the idea of John Garfield. I thought that was sort of an interesting guy to think about. And there was a Mitchum film called Out of the Past which I had never seen which was phenomenal. I’m really a fan of that kind of filmmaking. And Curtiz films.

Q: What is it that you’ve learned as an actor over the last few years?

Clooney: Well, you hope you’re pushing things and growing. Usually, cause y’know I write and direct and produce. And as a writer or director or producer I can look at things a little more objectively then you can as an actor. So, I can look at things that I wouldn’t cast myself in and go, ‘Ah, there are guys who could do that better than me.’ So, I think one of the secrets as an actor is understanding your limitations and then trying to push things every time and do things differently. And trying to grow, but not trying to think you can do all of it.

Q: Are there days when you don’t want to act other than directing yourself?

Clooney: No, not yet. That’ll happen. But, you’re right, it’ll happen. Look, if I get a chance to act with Steven or Joel or Ethan – I did this film with Tony Gilroy coming out, who did a wonderful job – if you’re doing a good script, there is nothing more fun than to be an actor in that. That’s exciting. Working with Cate. There isn’t a moment that’s boring. On this film, this is as hard as anything I’ve ever done as an actor because it’s a completely different style and you have to commit to it. You just can’t stand outside and wink. You have to kind of lay in and say we’re going to be overly earnest and overly,painfully, achingly direct and not internalize things. That’s really hard to do and try and find a level that makes it believable. So, no, not yet, but I’m also working with directors I really love. If I get to that point, I’ll much rather direct. I like directing better.

Q: How has winning an Oscar affected your life?

Clooney: It’s changed everything. I’m much taller. [Laughs] Y’know it’s a funny thing. It’s one of those interesting things, because it’s a nice thing and it always makes you feel good. But it makes absolutely no difference with the studio when you tell them you want to make a film. Even if you carried it and set it down on the table, it just doesn’t matter. They really don’t care. They’re happy for you, ‘Great. Great George.’ But it doesn’t really make a difference in my day-to-day life of getting things done. But it’s nice; it sits on the mantle. My friends will come over and pick it up and go, ‘Man, that’s heavy.’ It’s a nice thing.

Q: How much though do you have to balance the commercial work to make it all work?

Clooney: We have to do them. Clint set the bar. He understood exactly how to do that. We have an office exactly right next door – literally right next door and I’ve seen him for ten years every day. He gave a great pattern on how to do it and I think it’s a smart way of doing it: you do one that hope can make some money commercially and it buys you two smaller ones along the way. And that seems to be what we’ve been able to do.

Q: So even if the new Ocean’s movie makes a fortune, you wouldn’t come back to it and do another one?

Clooney: No, well, Thirteen happened because we felt like we could do it better than Twelve. We didn’t want to go out getting socked in the chin on one. We were both like, ‘We know how to do this.’ And we found a really good reason to do it, which is revenge, which is always better than just money. That made sense to us and we thought, ‘That’s a good reason to do it.’ There’s no other reason to come back. Who knows? Listen, ‘Rocky 17’? Who knows? Maybe ten years from now I’ll need a job and take it. But right now, we don’t plan on it.

Q: But hasn’t the dynamic of doing a big one and then a small one changed because of DVD? Doesn’t a film like Good Night and Good Luck actually have a chance to become profitable on home video now?

Clooney: It can. I think most of the time they lose money because it costs so much in the prints and ads. Good Night, and Good Luck is the best example. We spent less than any other film that was in our category in terms of prints and ads out there. It cost $7 million to make the film and it was probably $25 million in ads. That’s a lot of money. So, suddenly, you have a $32 million for a $7 million film, and we were the low budget one of those guys. So ultimately they made $35 million or something and probably about that overseas, so basically you’re breaking even and then they make money on DVD, but that doesn’t happen very often. We got lucky on that one. It’s a very interesting business. The DVD is where the money is.

Q: Now that you’ve directed yourself, are you more forgiving when working with a first time director like Tony Gilroy?

Clooney: I didn’t have to be forgiving with Tony. He really, really, really knew what he was doing. Sometimes you get with a director who is basically a first time director and they need a lot of handholding. I had one before that where there was a lot of work to be done. Tony is a grown-up. He knew what he wanted to shoot, he had a plan. The biggest thing with a first time director is do they shoot with a point of view? Steven shoots with a point of view, Joel and Ethan shoot with a point of view. That’s the secret – you don’t want to just collect footage and get in an editing room and create a film. That’s the difference.

Q: How difficult was it shooting Michael Clayton in New York?

Clooney: It’s always trickier shooting in New York, because you’re not going to get isolated anywhere. It’s very hard to get a moment, because there’s a lot of people around, but that’s also why you shoot in New York, because it gives you that energy.

Q: What led to the decision to shut down Section 8?

Clooney: But we decided that when we started it. Steven and I had a conversation about it two years before we shut it down where we decided it. We said seen all the other companies do this, which is about five years in, you stop being filmmakers and you start being administrators and businessmen, and we didn’t want to do that. Exactly what we thought would happen was happening. We were starting to have more meetings on ad campaigns and posters and trailers then actually making the film, and that was no fun for us. We were very clear about it. We tried not to screw with anyone along the way, so we said ‘Two years from today we’re done,’ and we did it and we’re very pleased with how that worked.

Q: And now you have a new production company.

Clooney: We started over, reset and start over and try again.

Q: What’s going to be the difference?

Clooney: Well, Grant [Heslov] and I have the same theories, which is you try to protect filmmakers, you try to get screenplays made that people didn’t want to make. All the same things. We’re having some luck. We just got the Grisham book and we’re having a really interesting time with some really interesting projects.

Q: One of the interesting things about this film is the shifting point of view.

Clooney: I really love the idea of changing the point of view – literally changing the lens – cause I thought the minute you started seeing the narrative change, you were like ‘Oh, this is really quite a way of telling a story.’ I was really excited by the idea of it. Also because in general, a 40s film like this is told by the male in it, and it really throws you because you think it’s about [SPOILERS! Swipe to read] Tobey Maguire and then… it ain’t. I remember the first time I saw Alien, when I went to the movie theatre in 1979, and you thought Tom Skerritt was going to be the star, because there’s always been the guy sort of surviving, and he was the handsome guy. And he bites it first and all of a sudden, you realize it’s Sigourney Weaver, and you’re really taken by the idea that point of view gets shifted a little bit, and I think that that’s really interesting storytelling.

Q: Is there a film that’s been more of a challenge then you wanted it to be?

Clooney: There are a few things. There’s a screenplay I’m working on now that I want to explore. The movie I’m directing right now is a football film from 1925 that’s been about 10-12 years of us trying to get this thing made. I finally figured the key to it out this summer and finished writing it. We’re going to start shooting it in about a month, so that was one that I just wanted to get done just it was making me crazy. Also because I didn’t want to do a political film next cause after Syriana and Good Night and Good Luck I got offered thirty different political… all of a sudden, everybody wants to do a political film and I didn’t really want to do that. I didn’t want to become that guy. But then I have an interesting idea about elections that I might want to do after that.

Q: You say you know how to do an Ocean’s film but I imagine you’re taking some risks in the third one.

Clooney: Yeah, it’s a very different version of that. It’s back to 11 in terms of spending more time with the guys, but it’s about revenge, which I think is just such a good motivator after you’ve had these guys make a lot of money. What are you going to do? “Let’s make some more money”? So this one is about just getting someone who wasn’t one of our guys, and I just love films like that.

Q: Don’t you see Good German as a political film because it has the theme of…

Clooney: How to screw up an occupation? [laughs] But I don’t know if there’s a comparison between now and the idea of sort of forgiving war crimes because that’s not really what we’re doing particularly right now in Iraq. That’s the one thing we’re clearly not doing. Given the de-Baathification we certainly didn’t forget any war crimes of any kind. I don’t know [The Good German is] overtly political. It’s certainly set inside an absolutely real event. There’s a great documentaries about not just the Camp Dora stuff, but how the German soldiers were desperately trying to surrender to the Americans for the two-car garage rather than the Russians where it wasn’t going to be nearly as nice. So I love that world but you know, it’s still at it’s heart and soul, it’s a romance murder-mystery, Chinatown, nobody wins, nobody’s good movie set inside a real world. So there are political underpinnings, but I don’t think they’re necessarily relevant to what’s going on politically here right now.

Q: So which is better, the Oscars or Sexiest Man Alive?

Clooney: I have to say Sexiest is big. I gotta say, it’s a big one, I use it. Brad is upset, but there’s still a time for him, he’s a couple years younger, so he still has a short. I think Matt was the most hurt. It hurt Matt.