The first two questions in this one on one interview come

The first two questions in this one on one interview come

from… a round table. I know, I know. The two things are completely the

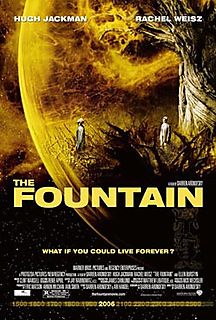

opposite. But here’s what happened: I flew to LA two weekends ago for the

junket for The Fountain, and I was guaranteed a one on one with Darren

Aronofsky. He’s quite fond of the site, and has said some incredibly

complimentary things about my reaction to his film, so I assumed this was a no-brainer.

Turns out that something got crossed and I was not scheduled for a one on one after

all. Bummed, I went to the round table anyway and tried to ask some of the questions

I had been planning to ask in the one on one. At the end of the table interview (if you want to listen to the whole table interview, Collider.com has the audio),

Aronofsky turned to me and said, ‘I’ll be talking to you again later, right?’ and

I had to tell him that we actually weren’t scheduled.

Much to his enormous credit, Aronofsky made time for me

during his incredibly busy junket day to do an unscheduled one on one

interview. I wish I had more time – hell, I wish I could sit with him and go

frame by frame through the movie. But I like what I ended up with, and combined

with Russ’ exclusive with him (click here) – Russ’ questions tended to the film

oriented – I wanted to know more about the themes and concepts of the movie – I

think CHUD has the best Aronofsky interview on the web.

Every element of every storyline, every timeline, is in every other timeline. It’s a very fractal picture. Everything is related. How did you build that in? Did that come in the script stage? Did you find those connections on set? Were they created in the editing room?

It’s all pre-planned. With the budget that we had, which was extremely low, and the limited amount of time, which was extremely short, to do something like this, it was all about homework. So, all those connections were made beforehand. Of course, things came up where we realized, “Hey, we could stick that here.” Things happened on set, but I’d say 95% of all decisions are beforehand. Because when you get to set, no matter how much two-dimensional work you do — meaning storyboards, shot lists, script work — as soon as you get into a three-dimensional space with real live actors and real physical equipment, nothing ever works out, so you have to be able to adapt.

But, having done all that homework allows you to know what you absolutely need, so you can get pretty close to getting everything you want. But all the woosh shots, the horse going by, the car going by, and the ship going by, that was all pre-planned. All the star fields that are going on throughout the film — in space, of course, and then the candles all hanging down, once you throw them out of focus, they’re a star field, the Christmas lights behind Rachel on the rooftop are star fields. From working with with darkness and light in the same way, where Hugh’s character is in the black and Rachel’s character is in the light. Hugh’s never really fully lit until the end of the film, and Rachel’s lit all the time. That was always planned, 10 months before we ever got to set.

You said that your next film was going to be something Biblical, your first film was about God and math, and this film is spiritual, in an agnostic way. What’s your take on God? Are you religious? Do you believe in God?

I think the themes of The Fountain, about this endless cycle of energy and matter, tracing back to the Big Bang . . . The Big Bang happened, and all this star matter turned into stars, and stars turned into planets, and planets turned into life. We’re all just borrowing this matter and energy for a little bit, while we’re here, until it goes back into everything else, and that connects us all. The cynics out there laugh at this crap, but it’s true. The messed up thing is how distracted we are and disconnected from that connection, and the result of it is what we’re doing to this planet and to ourselves. We’re just completely killing each other and killing the planet, and it’s a state of emergency right now, I think. All of my charity work has always been about the environment. There are 15,000 species on the endangered species list. Mercury poisoning is my new thing. We’re doing it to ourselves. The fact that there’s mercury poisoning in the breast milk of indigenous people in the North Arctic is all coming from us, and Alzheimer’s is on the rise. What are we doing to ourselves? It’s a complete disconnect. To me, that’s where the spirituality is. Whatever you want to call that connection – some people would use that term God. That, to me, is what I think is holy.

What’s unique about this film is that we don’t make movies in the Western world about accepting death. Death is something to be fought in movies and only given in to in the most heroic circumstances. In this film it’s part of the cycle of life – that’s a very Eastern thing. How did you come to this?

You know what? You’re the first person in the West to ask that question. I got asked that question all the time in Japan. In Japan every interview was, ‘How did you get this Eastern thing?’ I don’t know, to tell you the truth. It’s a little embarrassing to say, but back in the 70s as a kid I did a lot of karate, and I kept with it. I kept with it and I was into martial arts all the way through college. I’m still into it. I think that opened me up to writings on Zen and Buddhism. It’s a combination of a lot of ideas in there, but that’s what tilted me towards an Eastern POV.

Do you think that some of the negative reactions the film has gotten have come from people not being willing to look at death as a graceful, profound thing, or has it come from the film being very earnest?

I think it’s a few things. I think that if you’re not a fan of science fiction, then that first 20 minutes of the film might lose you. People cross their arms and they never reconnect. Because there’s a lot of big themes going on… it is very earnest, and we took it very seriously. I was surprised by the cynical reactions, and it was very clear. People have said, ‘Hey, it’s the age of cynicism, how can you do something like this?’ I say it’s not the age of cynicism. That was the 90s. When things were dandy. When David Letterman was king of the world. Now, in a post-9/11 world personally I feel like it’s OK to talk about things. The war is between are we going to end up in the age of superficiality with big, huge statues of Paris Hilton or are we going to say, ‘Hey what’s going on right now?’

I was actually stunned by that. But I continue to make films that are heartfelt because that’s just what comes out.

What do you think the public reception is going to be?

I’ve got no idea. We’ll see.

How much does it matter to you, how much the movie makes at the box office?

That’s not why you make a film. It’s funny – this whole 200 million dollar box office and the fascination with box office is, I think, one of the worst things for movies. Pi is, I think the 16th most profitable on the return film in the history of filmmaking. It cost a few thousand dollars and it made a few million dollars. That’s good business. I really am interested in getting the money back for my investors. That’s my main goal.

But making blockbusters is a dangerous thing because you boil it down to the vanilla factor. I call it the vanilla factor: if you ask a room full of 25 people to decide what their favorite ice cream flavor is, they’ll probably get to vanilla. That’s the problem with a lot of these films that are trying to connect with every single quadrant. Most of the time they get boiled down to something very simple. But then again there’s a film like Borat, which is really radical. And it’s a hit. You never know. Those are the films I’m interested in.

Where did Mogwai come in?

I always wanted a psychedelic rock element because there’s a psychedelic tradition here. It needed the rock and roll element. Clint [Mansell] knew Mogwai as a band and was a fan. The Kronos Quarter was always there and we got excited about the juxtaposition of those two things.

What do you listen to these days?

It’s been a little bit of a slow year. I got into Gnarls Barkley before everyone on the planet got into them. I was an early fan! I can’t wait for the new Arcade Fire album. I’ve been listening to a lot of Johnny Cash as always. But it’s been a dry year as far as inspiration from the music world. But I like the new Rick Rubin release of Johnny Cash stuff.

What can we expect on the DVD for this film? I was watching the movie last night and I couldn’t decide if I wanted a commentary that would give away every bit of symbolism and meaning or not.

There is no commentary. Warner Bros was not interested in it, so I did not push it. My whole thing is that I realized… Criterion was interested in Pi and Requiem, but because I put everything out on [the original DVDs], they didn’t really find a reason to do them. So when Warner Bros said they weren’t interested, I said, hey I’ll keep this in my pocket and eventually… I enjoy it because I got so much out of commentaries from other films I learned a lot.

So you’re telling me you want to do The Fountain as a Criterion DVD?

I’d love to.