I want to make Roy Frumkes the patron saint of CHUD.com; I don’t think there’s anyone in the film world whose sensibility is more in line with ours. Roy wrote and produced the splattery classic Street Trash, about bums that drink a tainted wine that causes them to melt and explode – a movie that features a bunch of bums playing keep-away with a man’s severed penis, and he says that he took his inspiration from Akira Kurosawa’s Dodes-ka-den. It’s the perfect merger of high and low art. I love it.

I want to make Roy Frumkes the patron saint of CHUD.com; I don’t think there’s anyone in the film world whose sensibility is more in line with ours. Roy wrote and produced the splattery classic Street Trash, about bums that drink a tainted wine that causes them to melt and explode – a movie that features a bunch of bums playing keep-away with a man’s severed penis, and he says that he took his inspiration from Akira Kurosawa’s Dodes-ka-den. It’s the perfect merger of high and low art. I love it.

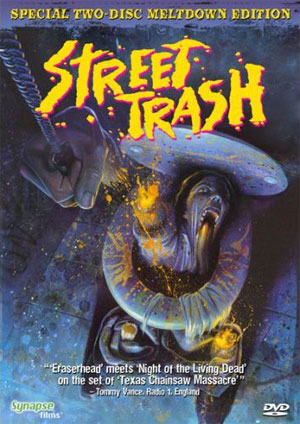

And I love Street Trash. The new 2 disc DVD from Synapse is an incredible set, with a beautifully restored picture, two commentaries, and Roy’s epic making of film, The Meltdown Memoirs. The set’s worth buying for the documentary alone, and some of that comes from Roy knowing his making ofs – he directed Document of the Dead, the legendary and definitive film about the making of George Romero’s zombie films. So many of the low budget horror films I grew up on have aged poorly, but Street Trash is just as funny, gross and utterly transgressive as it was the first time I saw it on Vestron Video in the 80s.

Jimmy Muro was the young prodigy who directed Street Trash, and he got to know Roy as a teacher at New York’s School of Visual Arts (SVA) (where Roy had a young Bryan Singer as a student. Singer worked on Street Trash and turns up in The Meltdown Memoirs with a great story about hauling around a carload of dildos). Together they made a movie unlike any you’ve seen before, and created a strange and un-PC and yet totally lovable world of bums and winos and aViper wine, which is guaranteed to fuck you up.

You must have Street Trash in your collection. Click here to order it now!

When I got on the phone with Roy, it turned out he had done some thinking about CHUD.

[Note: my damn recorder ate the second half of this interview. You’re really missing out, because Roy had some fascinating things to say about the indie film world, the DVD market and plenty of other topics. Maybe one day he’ll agree to another interview and we can make up the lost stuff]

Frumkes: I don’t know if you know this, but we have two degrees of separation. At the end of the Meltdown Memoirs, in the section on the distribution of Street Trash –

It has a foreign video cover for Street Trash with the CHUD poster art on it.

Frumkes: That was a Scandinavian release and they didn’t bother to do original artwork, they just grabbed the CHUD artwork. I have the box itself – it was so cheesy and skimpy of them to do that, but it’s a wonderful thing.  The other connection is that a guy who was a location manager on CHUD came into my class 21, 22 years ago and he’s the one who took the picture at the beginning [of The Meltdown Memoirs] with my classroom and me, and Bryan Singer is the student sitting nearest the camera in that shot. That was taken by a guy who had worked on CHUD.

The other connection is that a guy who was a location manager on CHUD came into my class 21, 22 years ago and he’s the one who took the picture at the beginning [of The Meltdown Memoirs] with my classroom and me, and Bryan Singer is the student sitting nearest the camera in that shot. That was taken by a guy who had worked on CHUD.

We’re like family, Roy.

Street Trash is a movie that I saw when I was 13 or 14, and it was a movie that was a revelation to me because it was so fucked up. It was hard to find in the years since, and I have come to judge people based on whether or not they had seen the movie. There’s a bit at the end of the Meltdown Memoirs where you point out how funny it is that you have the guy who restored Lawrence of Arabia restoring Street Trash… now, I love the 2 disc DVD, but is there a point where part of the joy of a film like this is that it was so hard to find, that you really had to work at seeing it? And that it was disreputable in a certain way, and that a beautiful restoration undermines that?

Frumkes: Two or three things about that. I was the one who kept it hidden away. I have the negative and it’s in great shape, and I stored it, but I felt over the years that the time wasn’t right. It couldn’t be re-released without my permission. So maybe I fed into the obscurity and hidden treasure aspect of it that you liked, and that you used as watermark for how serious your friends are about cult films.

The other thing is that Bob Harris is an old friend of mine. We went to college together, and we used to live in the same town. I used to go over to his house where he had built a little theater and we watched Technicolor, chopped-up prints of Lawrence of Arabia, and he used to come to my house and watch Tech 16 prints of War of the Worlds. So I asked him if he would do this bit for Meltdown Memoirs, just for fun. He agreed reluctantly because it would seem such an odd leap from Vertigo to Street Trash. So that was all done humorously. But in truth he looked at it; I did bring him the negative because it had been in storage all those years and I was about to put it on a telecine and have it run mercilessly back and forth to create the master. He gave it a passing grade. He said there were even three or four prints of it before it started to go. He urged me to make a new negative because he didn’t feel digital is the right realm to preserve things on – he feels there should be original materials recereated. But that’s an expensive process; I don’t know when I’ll get to do it.

But is there something about a cult film that, once we bring it into something as classy as this two disc set, that undermines the cult aspect?

Frumkes: I’ll tell you what I’ll do for you – I’ll put it back in hiding for 20 more years! Consider that a done deal.

The Meltdown Memoirs is great because it’s not just informative, it’s personal. You learn so much about the people who were involved. But the director is almost completely missing. Why is that?

Frumkes: A couple of reasons. Jimmy was 21 when he did Street Trash, and his life went through a number of changes after that, as happens to someone in their 20s. As opposed to me – I was in my 40s; it was too late for me to go in any other direction. I’m exactly what I was, more or less, when we made that film.

Jimmy wanted to direct more, but it wasn’t easy to do, especially with the kind of freedom he had [on Street Trash] because I had a particular attitude about how to produce a film, part of which I got from being on the set of Dawn of the Dead, which is that the producer is utterly supportive of the director. That isn’t really the way things are in this country – the producer and director are pals through the writing process, but once pre-production starts, their relationship sadly becomes adversarial because time is money and there are distribution things. I didn’t behave that way, and then the film went over schedule by about a month and I kept saying, ‘Great.’ He kept getting offers but they weren’t no strings attached. Meanwhile his Steadicam career took off like a skyrocket – he became, within three or four years, the premiere Steadicam operator on the planet. They would fly him first class to the set with two seats, one for him and one for the Steadicam. He was pulling down the kind of money he could never make directing, even today. So the idea of directing became less and less urgent for him.

of which I got from being on the set of Dawn of the Dead, which is that the producer is utterly supportive of the director. That isn’t really the way things are in this country – the producer and director are pals through the writing process, but once pre-production starts, their relationship sadly becomes adversarial because time is money and there are distribution things. I didn’t behave that way, and then the film went over schedule by about a month and I kept saying, ‘Great.’ He kept getting offers but they weren’t no strings attached. Meanwhile his Steadicam career took off like a skyrocket – he became, within three or four years, the premiere Steadicam operator on the planet. They would fly him first class to the set with two seats, one for him and one for the Steadicam. He was pulling down the kind of money he could never make directing, even today. So the idea of directing became less and less urgent for him.

In addition he became Born Again, like Bill Chepil, [who plays] the cop. I think the serious difference with that is that he began to find Street Trash something morally he had to distance himself from. Initially he showed it a lot in LA and all the directors – Cameron and those – loved it. But as the years went by he felt uneasy about it. When I started Meltdown and I approached him to get involved, he said the best he could do was not stand in my way. I said, OK, so be it. That’ll be a statement in itself. Fortunately I had access to that footage of him onset, so it wasn’t like he would be absent totally.

Towards the end he decided he would like to be marginally involved and so he did a commentary track. It’s a nice one because it really complements mine in the way that mine is anecdotal and I’ve never lost touch with the film and I know every frame, whereas his is more technical. They’re very different commentaries.

It’s too bad he didn’t get involved because he would have made such an interesting counterpoint to Bill Chepil who, while being born again, is so rambunctious. Maybe my favorite part of his section in the documentary is when we meet his son, who looks like a goth rocker.

Frumkes: Isn’t that fabulous? His son loves him, but I guess one has to break away as a teenager and go in another direction, and breaking away from Bill requires a major effort! They get along fine. I’m doing a convention this weekend called Cinema Wasteland in Cleveland, and Bill and the kid are flying in for it. They get along just fine, but he had to establish his own identity. I shot about an hour of him performing, but it just didn’t work in the documentary.

The first cut of Street Trash was two hours and forty minutes, and you have some of the deleted scenes in the Meltdown Memoirs documentary. Maybe the most extensive one you have there is the dance scene, which is just so great. Was there ever any thought of adding that back to the movie?

Frumkes: I’m so glad you liked that. By the way, that was Jimmy Muro’s favorite scene in the film. He thought that was going to be the highlight of the film, so it must have been difficult for him to let it go. The original scene was three minutes and forty five seconds long; I think we show about a minute of it. It was originally much more complicated, and it involved Bronson [the king of the bums]. Once we decided it wasn’t going to be used, elements of the Bronson footage was taken out and cannibalized and put into other sequences, like the hallucination sequence. We could never put it back together, really. But I do have it in its entirety, but it’s very degraded. I have it on a VHS that was shot off a steamdeck, off the editing machine, but it’s just so degraded. I tried to put the whole of what there was in the documentary but it wasn’t fun to look at.

You go over some of the original venomous reviews in the documentary, and they really make it seem too bad that the dance scene wasn’t in the movie – it could have helped people get the tone of the film.

Frumkes: I agree with you, and that’s very smart. What happened was it that we started showing the original cut to distributors and they said, ‘You can’t release an exploitation film  over 90 minutes.’ As it is, it’s 102. They said George Romero is the exception that proves the rule, and they wouldn’t touch it [if it was long]. We liked the long cut, but we didn’t have the kind of money – we had the money to do the film right – but we didn’t have the money to make a copy of the long cut for preservation purposes. So we did a much tighter cut, and the scenes that went tended to be scenes like the dance scene that didn’t advance the story but provided some flavor. But at least we get to see some of it on the documentary.

over 90 minutes.’ As it is, it’s 102. They said George Romero is the exception that proves the rule, and they wouldn’t touch it [if it was long]. We liked the long cut, but we didn’t have the kind of money – we had the money to do the film right – but we didn’t have the money to make a copy of the long cut for preservation purposes. So we did a much tighter cut, and the scenes that went tended to be scenes like the dance scene that didn’t advance the story but provided some flavor. But at least we get to see some of it on the documentary.

There’s a funny bit in the documentary where there’s an intermission and I’m urged to go to the bathroom and eat chocolate. What was the impetus behind that?

Frumkes: My time of getting into cinema was the late 50s through the mid 60s. That’s when I was becoming aware of what cinema was, and it was the time of the epics, of Ben Hur and the Ten Commandments and El Cid and Brando’s Mutiny on the Bounty, and they all had intermissions. All my life I wanted to do a movie with an intermission, and this was my opportunity! I remember the screening we did for Don May, the president of Synapse – he saw it a year ago, before we found Vic Noto and Clarenze Jarmon (that was what held me up in getting it finished, and I had ads up on the internet offering rewards to find these people), and he saw it before we had them and he liked it. Then the intermission came on and he was like, ‘What the hell is this?’

The delay was worth it just to get Vic Noto, who played Bronson, king of the bums – he’s mad.

Frumkes: He’s wonderful. He called me last night; he finally saw it and he loved it, which I was thankful about – I was apprehensive about how he would react, because he can be touchy. But he was floored by the film and all the stuff that I still had; I still had his audition. He was very happy. He did say, however, kind of quietly, ‘What did Mike Lackey [the film’s star, and eventual Spider-Man comic book writer] think of it?’ [in the Meltdown Memoirs, Vic Noto has some less than kind things to say about Mike Lackey] I told him that as long as I made fun of myself then I could make fun of him too. Vic said, ‘I like him, he’s a good guy. I’m sorry I said that stuff!’

The other thing is that music that plays under the intermission is music I wrote. I wrote some of the music for the movie, so I finally got to use it.

One interesting thing about watching Street Trash as a New York City boy is that it’s a time capsule of the last time New York City felt like New York City to me. You look at the places where you shot the film back then, locations that were crummy and dirty, and now they’re hipster and yuppie enclaves, like Greenpoint. You went back to some of these locations for the end of the Meltdown Memoirs; what was that experience like, going back and seeing organic food stores and hip cafes?

Frumkes: I went back to the corner where I melted [Frumkes cameos as a guy who gets acidic bum ooze on his face] and I couldn’t see it. I was looking at it and it was so transformed that I couldn’t see the past there anymore. It was really odd. There were some locations that were almost disconcerting, they had changed so much. And there were others where I thought an audience could almost superimpose and see, like the collision yard.

where I thought an audience could almost superimpose and see, like the collision yard.

But yeah, it’s been a major change. I think I’m going to quote you on that – I like the way you put it. I do feel that the film, because of the art direction and the make up and the characters and all, the film hasn’t dated much. Even though New York has changed around it, the film has a Road Warrior-ish feel.

You’re a member of the National Board of Review. I’m always so curious about them because they’re so secretive –

Frumkes: Here’s your chance!

I’m taking it! How does the NBR work – these are people who are not necessarily critics. How do you get into the NBR?

Frumkes: A brief history, which you may already know: it started in 1909, before feature films were being made, but there was already mass censorship going on in the United States. Religious leaders would come up to the booth and hack films to shreds. There were groups of citizens who were concerned about it, and the industry wasn’t really together yet, so well-intentioned citizens organized the board and put this little thing that you see on old movies from the 20s to the 50s, saying ‘Passed by the Board of Review.’ They would never lay hands on it for censorship purposes; they would look at it and kind of say, ‘It’s OK,’ 95% of the time. And that worked – it prevented local communities from getting involved.

It went on until the MPAA, and then we remained as kind of an impotent organization, because we had Films in Review magazine and we were well known. We were an institution. I joined when I got out of college in 66. You join only by being recommended, and one of my mother’s friends down the block was a member, and she recommended me. For the first twenty years I was their token young liberal. It was all these old people. Everytime we would see a movie they would say, ‘Oh my God, they’re using color now?’

For some reason in the early to mid 90s it came back to prominence. I can’t say why, but maybe a changing of the board of directors gave an effort to try to make it more visible again. Hollywood glommed on to it because we’re the first major organization to announce our winners – before all the end of the year films are out they show they us the films without end title sequences and stuff. Hollywood is superstitious, and they think in some way that we may be predicting the Academy Award winners, so they send everybody to our show. It’s like an East Coast Academy Awards, but it’s very casual. You just stroll around and chat with David Lynch and Clint Eastwood. It’s great fun.

What’s interesting about NBR is that you guys see ALL the movies that come out, not just the ones that’ll end up making your top ten list.

Frumkes: I’m a guy who loves movies, and I make one every four year, but what’s amazing is that the filmmakers show up to all of our screenings. It’s priceless. I’m seeing Volver on  Tuesday, and Almodovar is going to be there. Eastwood has shown up for everything over the last ten or twelve years. And they just sit and talk with us, and it always makes the film better. Even if we don’t like the film, once you get the people in there talking and shedding light on what went right and what went wrong – it’s a wonderful organization.

Tuesday, and Almodovar is going to be there. Eastwood has shown up for everything over the last ten or twelve years. And they just sit and talk with us, and it always makes the film better. Even if we don’t like the film, once you get the people in there talking and shedding light on what went right and what went wrong – it’s a wonderful organization.

You’re going back to Document of the Dead, right?

Frumkes: Four years ago when I did the licensing deal with Synapse for Street Trash, Don May innocently asked if I would want to do a little making of about the film, and I said, ‘Hmmm…’ and four years later Don was sitting there, weeping. But he was good about it – he never asked about it and he was happy with the results.

He also said – and I’m sure he’s regretting it – ‘How about an update on Document?’ I did this little TV special called Dream of the Dead for IFC about Land of the Dead, but it just scratched the surface. So I said, ‘Yeah, I’ll do the definitive Document of the Dead.’ I called George, and he’s getting ready to do another one called Diary of the Dead, and I said, ‘George, you may keep going on forever, but after this one I’m turning it in!’

When I did Document of the Dead, there weren’t any others like this. There were making of films from Hollywood, for films like Butch Cassidy or Star Wars, but there was nothing for independent films, so I was the only one on the set. It turned out to be a nice film, and it became what it is. But now everybody gets on George’s sets, and the world being what it is you need a making of for the DVD and a commentary track. So I figured for this one, which is going to be an addendum – I’m going to trim down the original a bit and add thirty or forty minutes – but it’s going to have to be radically different. I don’t want to give away much, but about two thirds of it is in the can, and I’ve got great stuff. I’m trying to make this a pyrotechnic finale.

Being on Land was difficult because it was done with Universal Pictures and I couldn’t do anything for Document of the Dead, I could only do it for Universal. The Independent Film Channel had been trying for some time to get on to the set without luck, and when they threw my name out there, it was accepted. They hadn’t called me yet – they had just smartly tried it. When I got up there I thought it was George who had said yes, so I thanked him, and he said, ‘I didn’t know anything about it!’ But it was clever – I guess my name means something in relation to George’s work.

What else is next for you? You’re still at SVA?

Frumkes: I retired a few years ago but they asked me back, so I’m just having fun. I have an international cinema class where I showed a double bill of Hiroshima, Mon Amour and Godzilla. I’m almost daring the school to step in and take action against me.

I’m also doing a class I’ve never done before called Finance and Distribution, because I am afraid for the students who are getting ready to graduate, that they think because of the digital revolution they can just make movies and get them out there when in fact there are ways that the industry has turned drastically against the indies in recent years. I want them to be really informed and armed.

afraid for the students who are getting ready to graduate, that they think because of the digital revolution they can just make movies and get them out there when in fact there are ways that the industry has turned drastically against the indies in recent years. I want them to be really informed and armed.

The digital revolution seems to have created a situation where it’s actually harder to find films of value because there are just so many to wade through.

Frumkes: You’re exactly right, that’s part of it. That is a major part of it. So they have to be aware of marketing before they write the script – they have to be aware of the arc of their film before they put any money into it, otherwise it’s just going to be a vanity production.

But the other thing also is that Hollywood hasn’t sat by idly and watched the indies flourish – they’ve taken very calculated moves to undermine the indie movement, and it’s working. It’s tough. I want to make all those things clear. It doesn’t affect me too much – I do my film every four years, regardless of Hollywood. I’ve done only one thing for Hollywood, which was the Substitute franchise, which was very lucrative for me, but by and large I avoid them.

When the definitive Document of the Dead is done, I have two narrative features I’m going to try – I’m very excited about them.