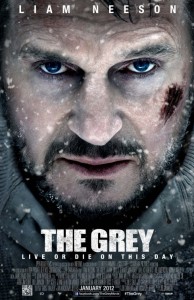

Renn Brown: As Liam Neeson has become middle-aged badass Number One in Hollywood, there’s grown the expectation that any character he plays is going to be hyper-competent and ahead of the curve at every turn. In The Grey, we definitely get a familiar version of that Neeson character, but rather than being an almost supernaturally trained killer or whatever, we instead see a desperate man who is above all else a wounded survivor.

Renn Brown: As Liam Neeson has become middle-aged badass Number One in Hollywood, there’s grown the expectation that any character he plays is going to be hyper-competent and ahead of the curve at every turn. In The Grey, we definitely get a familiar version of that Neeson character, but rather than being an almost supernaturally trained killer or whatever, we instead see a desperate man who is above all else a wounded survivor.

This character is so much more interesting.

Amazingly, with The Grey blow-em-up director Joe Carnahan also manages to turn his own filmmaking style on its ear, delivering a genuine adventure thriller that is also a true-blue introspective character piece. Fleshing out a tight, interesting script with great performances from a (perpetually shrinking) cast, Carnahan has undoubtedly stepped up his game and delivered the most consistent and fascinating film of his career, even delivering some art-film flourishes that feel right at home with his style. It all marries together into an incredibly propulsive action movie that is exciting and dangerous to the last frame. I can only hope it will end up a harbinger of the quality of this year’s films, rather than an early peak.

What you may notice right away as you’re introduced to Ottway — a contracted wolf hunter who guards Alaskan oil pipeline workers — is that this is a man who has quietly hit bottom and that no character could be farther from a dormant super-spy. The character immediately states in no uncertain terms that he is right where he belongs among a commune of assholes and outcasts, with only an unsent message and the glowing memories of a lover for companionship.

Early in the film there is an elegant scene in which Ottway quite simply does his job; assassinating a wolf as it moves to kill a pipeline worker. There is something isolating about this moment (the man he saves is distant, his work continuing as if nothing had happened), and it demonstrates that Ottway is simply an ugly, lonely cog in the cold, faraway mechanisms of the world. The scene is much more effective representation of man’s current relationship with nature than any clumsy montage of forests being torn down by giant machines or towering smokestacks belching out gas. Perhaps a bigger problem than our ruthless disregard for sustained living is that man has distanced himself from nature, systematized his exploitation so that animal-like survivalist greed has become dispassionate efficiency. So when a few moments later nature literally rips Ottway out of the sky and puts him face to face with the tundra’s wrath with no distancing weapon and no high ground, it seems rather like a destiny we should all fear.

But aside from lofty subtext, one of the many wonderful things about The Grey is that when Neeson’s character confronts crisis and steps up as we all know he must, he does not become the unrealistically competent hero, but just a guy with a few more facts and some common sense survival skills. What actually makes him the alpha-male among the group of men who survive with him is not that he’s the one that thinks to tape shotgun shells to pointy sticks, but that he has the latent compassion in his heart to ease a mortally wounded man into death with comforting words. The few rough-edged guys that survive the wreck — Dallas Roberts, Frank Grillo, Dermot Mulroney, Joe Anderson, Ben Bray, James Badge Dale, and Nonso Anozie in roles of quickly diminishing screentime — know in their hearts that “every man for himself” is a sure a road to death and while they don’t see the same pain and longing in Ottway that the audience does, they know who among them has the best chance of guiding them to safety. Still, even armed with Ottway’s understanding of wolf behavior, they have only what they can carry and what bravery they can muster at their disposal.

It will not be enough for most, or perhaps all of them.

Early in the film, at Ottway’s suggestion, the men begin collecting the wallets of the dead so that they may have a record of who was with them. Surely it’s no surprise that near the end of the film a very few men are carrying a great many wallets, and that the driving force of the film is death. It’s incredible how such a limited number of men are picked off so quickly without the film grinding to a halt 40 minutes in, yet somehow the entire length of the film is never without a sense of danger punctuated by a gruesome attack. Moments of rest are few, and it keeps adrenaline flowing through your veins till the credits roll. The wolf effects are a mixture of practical work and detectable CGI, but they are never less than convincing and never robbed of their menace largely due to the sharp filmmaking.

Carnahan is an absolute beast with his camera, and sub-zero temperatures don’t prevent him from injecting urgency and chaos where it fits, and tense calm elsewhere. Grainy photography and handheld camerawork intimately sell the reality of an almost supernatural threat. It’s unlikely that the wolves in the film hold strictly to true wolf behavior (that would have surely made for either a prohibitively short, or unbearably long film), but these aren’t just wild animals or even manifestations of an angry Earth. These creatures are specters of a shared primal fear of death that all men share, and all men must face at their weakest moment.

Each member of the cast, for as long as they are around to do so, perform gamely as men not used to being vulnerable. Mulroney, Anderson, Grillo and Roberts all have especially wonderful moments, while the ensemble as a whole feels perfectly authentic at each turn. It must be said that with them all bundled, covered in frost, and yelling it can sometimes be tough to keep track of who is who, and with character arcs often (and decidedly) snuffed out without warning, it’s no surprise that Neeson owns the film. Still when the other cast have their moments to shine or take a scene, each and every one adds something beautiful to the film’s meditations on death and vulnerability. Kudos should also be given to the sound crew as well for a remarkable vocal track and mix that keep dialogue audible while selling the cacophonous power of the near-arctic winds.

Much ado has been made of the trailer’s images of Neeson moments away from fist-fighting a snarling beast and while that represents the attitude and energy of the film in a very roundabout way, at the core the film has a very different priority. The cold tundra is not the scene of a man’s last stand, but rather a blindingly white purgatory for a whole group of men chased by similar demons. What we see is the different ways men deal with those demons and how differently they face the same inevitabilities. Thus the surprise of The Grey is not just how thrillingly satisfying it is, but how emotionally and intellectually provocative it manages to be and how you’ll find yourself affected by it hours, days later.

This is Joe Carnahan’s very best film, and one of Liam Neeson’s best in years. We must all cross our fingers very hard they continue to find projects as beautifully nuanced and exciting as The Grey. For now though, we can all enjoy the first best movie of 2012.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars