This film is playing at the 44th New York Film Festival

This film is playing at the 44th New York Film Festival

at Lincoln Center. It’s playing Saturday, September 30th at 9 and Sunday, October 1st at 2:30. For information on how to get tickets, click here. Be aware that even if a show is sold out there will be a Rush line, where you may have a chance to get seats.

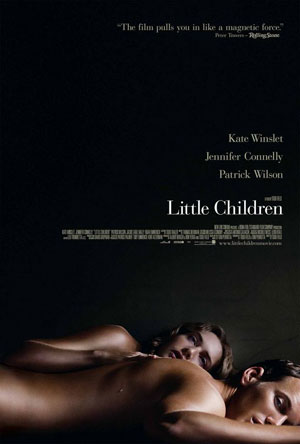

Walking out of Todd Field’s adaptation of Tom Perrotta’s novel Little Children (Perotta collaborated on the screenplay), I found myself having a mental debate – had I just seen a great film or a Great film? Little Children is bursting with fantastic performances, filled with great and often hilarious dialogue, structured with layer upon layer of resonant meaning and shot with gorgeous, masterful camerawork. The film works on every single level, but it’s going to take multiple viewings to decide if it earns that capital G – mainly because it will take multiple viewings to fully examine everything Little Children has to offer.

What’s most impressive about Little Children is the way that it maintains its odd, almost quirky tone throughout – Field finds a perfect balance on the fulcrum of drama and satire, all the while slowly and deliberately ratcheting up the tension until you find yourself in the strange position of sitting on the edge of your seat, laughing. The movie is filled with characters that could be caricatures and gives them depth and treats them with humanity. That doesn’t mean Field is kind to them – the movie is unsparing in exposing their flaws and hypocrisies and stupidity, but it’s just as rigorous in presenting them as complete people.

Kate Winslet is Sarah, once an independent feminist woman and artist who has now found herself trapped in suburbia with a husband who is growing more distant by the day and a daughter she just can’t relate to. She brings the child to the local park every day, where her own shortcomings as a mom are highlighted by the other mothers – uber-soccer moms who strictly schedule their children’s lives, with snacks served with military precision. Sarah, of course, tends to forget the snack.

One day the Prom King (Patrick Wilson) shows up with his son. He had once frequented the park and his handsome, manly presence freaks out the other moms – knowing he’ll be there they need to put on make-up and dress their best, even though they never talk to him. He’s known as the Prom King to the moms, but his name is actually Brad, and he’s a stay-at-home dad who’s studying for his third attempt at the Bar Exam. His continued failure makes him feel inadequate, which is compounded by his driven, successful documentary filmmaker wife, played by Jennifer Connelly. Sarah ends up talking to Brad just to show up the other moms, and they soon become friends, mutual outsiders in suburbia. And as time goes on they also begin an affair.

Meanwhile, Brad has been shirking his Bar studies and ends up hanging out with Noah Emmerich’s Larry, an ex-cop who is part of a night football league and also the leader and sole member of the neighborhood committee dedicated to protecting local kids from recently paroled sex offender Ronny (ex-Bad News Bear Jackie Earle Haley), who is trapped at home with his mother, battling his own impulses. Larry has a dark past of his own, one that drives him to become completely obsessed with harassing and exposing Ronny to the point of tragedy.

Looking back at those two paragraphs I realize this film doesn’t sound funny at all. Some of the humor in the film comes from the ironic and omniscient narration, delivered in a wonderfully stentorian tone. But much of the humor comes from the delicately realized absurdities of real life, often serving as a counterpoint to the growing sense of dread Field cultivates.

It’s no exaggeration to say that Little Children has the best performances of the year. Kate Winslet is getting the most buzz from her astonishing work playing a bad mother we can love and root for, a role that is probably going to earn her an Oscar nomination. Patrick Wilson, who has been slowly making his name with things like Angels in America and Hard Candy, gives Brad a perfect tinge of sadness while Emmerich presents Larry as a monster in almost the Universal Pictures sense – he’s destructive and terrible and yet, in the end, sympathetic.

Which brings us to Jackie Earle Haley as Ronny, the standout performance in a film filled with standout performances. The work that Haley does here is, without any doubt, deserving of a Supporting Actor nomination… and win. Ronny isn’t whitewashed, but he is layered. Ronny’s crime wasn’t sexual abuse but exposing himself to minors; when he’s first introduced, coming to the town pool to cool off in a heat wave, you’re torn between feeling bad for him when everyone freaks and feeling creeped out as he swims under the water amid the naked legs of all the children. The movie – and Haley – never quite lets you decide on where you stand with him, and it’s brilliant. We see that Ronny has urges that are sick, and we also see that he’s fighting them, and sometimes sublimating them in truly horrific ways. In one scene he goes on a date with a mentally fragile woman (ever-typecast as the crazy Jane Adams) and does something so gross and so horrible that it becomes easy to hate him. But Field and Haley won’t allow that to happen, and Jackie Earle really gets an assist from his screen mom, Phyllis Somerville, the only person who still sees the human being inside the pervert.

The conflict between Larry and Ronny mirrors and underpins everything else in the film – these characters struggle against their situations and stations in life, but also against themselves, against their own flaws and weaknesses, but most of all their own fears. Larry drowns the neighborhood in fliers with Ronny’s mug shot, creating an atmosphere of exaggerated terror, a situation all too familiar to anyone who follows modern politics. Little Children is about how giving in to these fears – whether they be fears of being trapped in a life you never wanted, fears of losing your masculinity, fears of mysterious predators in our midst, fears of your own uncontrolled urges – can lead to personal destruction. And how facing those fears can, sometimes, lead to redemption.

Little Children may draw comparisons to Desperate Housewives – it’s a suburban setting where manicured lawns and rigidly scheduled play dates mask deep dysfunction. And there’s a voice over. But that’s all surface – the TV show is a black comedy as opposed to a satire, and the characters are each more buffoonish than the last. Plus Desperate Housewives could never hope to match the raw intelligence of Little Children – it’s a movie that engages you emotionally but also intellectually. Perrotta and Field don’t shy away from asking the audience to actually think about who these characters are to consider why they’re doing what they’re doing. Field doesn’t rely on sweeping strings to give you an emotional cue, and his camera doesn’t manipulate you into feeling certain ways. This will annoy some audiences, who will feel confused by who they should or shouldn’t like and who would prefer a film that takes them by the hand and spells everything out.

I still haven’t decided if Little Children is capital G great, but if it is, it’s very much due to that aspect, the way that Field treats his audience as literate and engaged viewers. Little Children is a movie that aims high and more often than not achieves that altitude. Field and company have crafted a film that entertains as well as speaks to us about ourselves and the world we live in. Too few films bother to try that, and even fewer succeed. Little Children is one of the best films of the year.