Growing up, I never realized that the Godzilla I watched on Saturday afternoon TV – the black and white original film – wasn’t the same movie Japanese audiences had seen. The Japanese film Gojira had been recut for American audiences, and Raymond Burr had been inserted into the action to give us gaijin someone to root for.

Growing up, I never realized that the Godzilla I watched on Saturday afternoon TV – the black and white original film – wasn’t the same movie Japanese audiences had seen. The Japanese film Gojira had been recut for American audiences, and Raymond Burr had been inserted into the action to give us gaijin someone to root for.

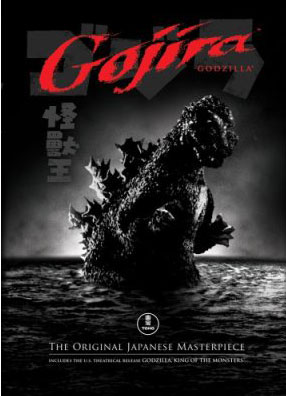

A couple of years ago the original Japanese Gojira finally made it to US screens, and now for the first time ever (believe it or not), that film is being released on American DVD. It’s a 2-disc set that has both the original film and the Godzilla you grew up with, as well as a bunch of special features. Also included on both films are commentaries by Godzilla experts Steve Ryfle and Ed Godziszewsky. I recently had the chance to get on the phone with Ryfle, author of Japan’s Favorite Mon Star: The Unauthorized Biography of Godzilla, and we talked about the past and future of the King of All Monsters.

The Godzilla-Gojira Deluxe Collector’s Edition is on sale now. Click here to order it from CHUD.com.

What was your first experience with Godzilla?

Ryfle: I was about four years old and I was going through that period that a lot of little boys go through – it must be genetic, handed down from prehistoric times – where boys are fascinated by dinosaurs. The first time I saw it my mom was flipping channels and I was like, ‘What’s that!’ I had to know everything. What’s interesting is that my mom saw the original Godzilla with Raymond Burr in theaters in 1956, but she didn’t like it because she thought Raymond Burr was kind of boring – but she liked the monster parts.

What is it about this monster that has made it so enduring?

Ryfle: We watched everything growing up – this was before video when you could get anything at any time. Growing up we watched any monster movie, but what stood out about the Japanese films in particular are their sense of imagination. They take place – especially the films of the late 50s and early 60s – take place in a kind of alternate reality. I always found a lot of the American giant monster movies kind of boring. I would sit there waiting for the monster to show up. They were so dry a lot of the time, and they were so interested in the cause and the relationship between a nuclear explosion or a genetic experiment or whatever it might be, and the monster. My favorite example is The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, which opened with a nuclear bomb. You see the explosion and you see the monster come out from under the ice – how much more direct can you get?

The Japanese films reinvented the genre in its own image. The films became less and less concerned with that, and had a world where giant monsters just exist. Who wouldn’t want to live in a world like that? I would.

The interesting thing about watching the original Gojira is how campy it isn’t compared to the later films. When does that change take place, and why?

Ryfle: I think it changed gradually. When Toho made Godzilla and continued in the genre, those films were generally patterned after American giant monster movies. You can see those parallels in Godzilla and in Rodan and in some of the other ones. Those film not only paralleled American giant monster movies, but they also reflected what was happening in Japan to a certain extent. They were always intended as entertainment films, but there’s subtext – which has never been more apparent than in the first Godzilla film. Everybody talks about it as representing the atom bomb, but more direct than that it reflected the Lucky Dragon incident and all the paranoia it caused in the spring of 1954. That was only two years after the occupation and the country was in a rebuilding mode.

As you get into the late 50s and early 60s the country starts to get more prosperous and the economy starts to boom. The film business really takes off – that decade between ’55 and ’65 is the most prosperous decade in the history of Japanese movies. For a couple of those years in the late 50s Japan was making more movies than any other country. The Godzilla films in particular started to reflect that prosperity. They almost always contained some sort of social comment, but they got more diluted. Still, King Kong vs Godzilla and the original Mothra, these films are comments on the side effects of Japan’s prosperity. They feature these greedy, capitalist promoters who are ruthless and who put people’s lives on the line to make a profit.

What’s Godzilla’s current situation? Will there be more Godzilla films?

Ryfle: Commercially he’s on hiatus right now, but Toho has made it clear that they intend to resurrect Godzilla, but they’re waiting for a time when the tickets will sell again. The last series of films, which ended in 2004, weren’t really setting the box office on fire in Japan. Godzilla movies have a following in Japan but in a large part they’re considered old fashioned. Japanese films in general have a tough time at the box office because they have to compete with American blockbusters – for better or worse, that’s what Japanese audiences tend to go see. It’s very rare that a Japanese film will top the box office charts unless it’s a Miyazaki film.

The Godzilla films have really struggled at the box office, so they might be waiting to see if there’s a way to reinvent the character so that it’ll have appeal for kids today. The last few films seem to have been geared to the nostalgia crowd.

What was the Japanese reaction to the American Godzilla?

Ryfle: I think they hated it. [laughs] I think they were just as disgusted, if not moreso, as the American fans were. They made a movie called Godzilla, but it wasn’t a Godzilla movie. It was Jurassic Park IV. The filmmakers probably didn’t understand the character and how recognizable it is.

The summer after it came out there was a Godzilla convention in Chicago, and they invited several special guests from Japan, including the man who played Godzilla from 1984 to 1995, Kengo Nakayama, and they showed the American Godzilla film. When the first scene where Godzilla appears, where they have the big reveal and Godzilla walks into Flatiron Square, Nakayama got up and walked out of the theater. He was livid, because that’s not Godzilla. He was pissed off – and not just because it looked different. It acted different. It ran away from the military; it didn’t behave the way we know it behaves. I think they could have gotten away with changing the appearance to a certain degree – although they changed it pretty radically – if it actually behaved like what we expected it to behave like.

As a very hardcore Godzilla fan, are there any redeeming values in that film for you?

Ryfle: On its own, if it were called Giant Lizard, I don’t know – I would probably feel very different about it. It’s not a great movie on its own – there’s this script problem where you don’t know if you should be cheering against the monster or feeling sorry for it. It’s a mother, and they’re killing her children. All it really wants to do – and that’s another thing that makes it different from Godzilla, this thing’s primary motivation is reproduction. And that’s never been Godzilla’s motivation.

Is there anything redeeming about it? Some of the special effects are OK. [laughs] You know, it went through a lot of permutations before it finally got made, and one version had Godzilla fighting King Ghidra. That would have been something.