Before we get to this week’s reviews, we’d like you to enjoy the first of what we hope will be a series of columns on topics of general interest to comics readers. Take it away, Bart!

Against “Continuity”

Against “Continuity”

By Bart Bishop

Here’s my personal philosophy on continuity: there is no continuity. To bring this into perspective will require a trip back in time, and a quick overview of the architect of philosophy: Plato.

The Classical Greek philosopher Plato discussed, in his canonical work The Republic, the concept of Forms. His Theory of Forms arose in response to the question of Universals. That is, is there an Absolute Reality or does the individual create reality through perception? Plato wrote that the material world as it seems to us is not the real world, but only an image or copy of the real world. The Forms are archetypes or abstract representations of the many types of things and properties we feel and see around us, Universals that can only be perceived by reason. Therefore, there are two worlds: the apparent world, which constantly changes, and an unchanging and unseen world of Forms, which is the Universal, Absolute Reality.

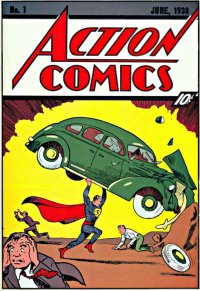

Furthermore, art is mimesis. That is to say, art is an imitation of perceived reality, and perceived reality is our interpretation of absolute reality. But comic books aren’t the kind of art that Plato imagined. Maybe the accepted first superhero comic book, Action Comics #1 (1938), was a product of art imitating perceived reality (after all, what is perceived reality if not the imagination?), but every superhero comic since then has been art imitating art. This is known as Continuity, the consistency of characteristics of persons, plot, objects, places and events seen by the reader or viewer over some period of time.

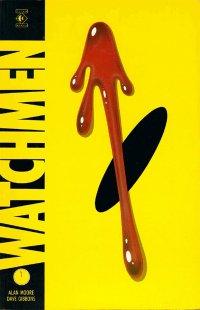

Continuity must not be hard to maintain when there is a single text, say Action Comics #1 or Watchmen. The difference between these two examples is that the former became the offspring of a franchise, and the latter has stayed a self-contained text (although probably not for long). Focusing on the former circumstance, there are differing levels of continuity with any ongoing franchise: Essence, shared history, script, and art. Taking all of this into account, it is apparent that continuity has no link to any Universals. The Absolute Reality of Superman, for instance, exists independently of the material floppy book, but not as a Universal. The “real” Superman only exists in the Jungian Collective Unconsciousness, somewhere intersecting between the reader and the creator. Continuity is, therefore, an agreement; an unspoken contract between reader and creator(s) that is maintained through sheer force of collective will alone.

Starting with Essence, this is primary characteristics that stay consistent across all variations: Superman, for instance, has maintained certain attributes since 1938. The blue, red and gold color scheme; the S-symbol; the black haired, Caucasian male who is both mild mannered Clark Kent and Man of Tomorrow; the fight for Truth and Justice; and the narrow escape from Krypton. If there’s any pure representation of this concept, any ur-Superman, it’s the first page of Grant Morrison’s All-Star Superman.

Shared history is a little trickier. Most comic fans are aware that the last seventy years, mostly focusing on the Big Two (DC and Marvel), have been divided into ages: The Golden Age (1938-1951), the Silver Age (1954-1969), the Bronze Age (1970-1983), the Dark Age (1984-1996), and the Prismatic Age or Renaissance (1997-2011). This is my own rough classification, cribbed from Grant Morrison and others, so take it with a grain of salt. Whereas Marvel has a relatively linear shared history since Namor’s first appearance in Marvel Comics #1 (October 1939), in the case of DC their Ages tend to signify alternate shared histories and alternate Earths. The Golden Age was Earth 2, a world in which superheroes appeared in the years leading up to WWII. The Silver and Bronze Age were Earth 1, an Earth where the heroes stayed relatively ageless, governed by “comic time” to stay relevant. That all ended with Crisis on Infinite Earths in 1985-1986, and for twenty five years New Earth had a shared history that combined elements from the other Earths (1, 2, and others). Recently with 2011’s New 52 Reboot, there’s yet another New Earth that has borrowed elements from all the earlier shared histories. What’s important about shared history is it tries to stay true to the Essence, often bending the narrative as a result.

Even with an unbroken shared history, Marvel has a sliding scale of “comic time” similar to DC Comics. John Byrne, writer and artist famed for runs on Uncanny X-Men, The Fantastic Four, and The Man of Steel, has stated every seven years our time equals one year comic time; Grant Morrison has said every five years for Batman. This is all arbitrary, really, and only meant to allow for younger characters (like Dick Grayson and Kitty Pryde) to become young adults. That’s a problem to discuss on another day. Whenever Marvel tacks down a character with a specific historical event, eventually it gets updated: Tony Stark, for instance, originally became Iron Man during the Vietnam War, and then in the 1990s it was updated to the first Persian Gulf War, and yet again to the war in Afghanistan during Warren Ellis’s run. This is not true, however, for all characters, as Magneto is still identified with WWII and The Punisher with Vietnam, but both have undergone extraordinary circumstances to stay young (circumstances that stretch credibility, perchance, but circumstances nonetheless).

So when a writer sits down to craft a script, they have to take into account both the Essence of a character and the shared history that character maintains within their own current books and within the entire shared universe. This is impossible. A writer can stay consistent with their own interpretation of a character, but no two writers can ever perfectly mimic the other’s interpretation. Grant Morrison, Geoff Johns, and George Perez may all write Superman in Action Comics (2011), Justice League and Superman, but they can only ever achieve a close approximation of each other. Either a writer will try to capture the Essence of a character, or try to imitate another writer’s interpretation, thus taking into account shared history, but no two writers’ versions of Superman will be exactly the same, no matter how hard they try.

So say, for instance, a character has only ever been written by one writer. Tara Chace, the protagonist of Greg Rucka’s Queen & Country, springs to mind. She has only ever been written by Greg Rucka, across many volumes of graphic novels as well as prose novels. This would allow for, one would imagine, a consistent continuity, a true reflection of “what really happened” because the character and the plot originated from one mind. The words produced by that mind, however, are translated into visuals by the artist, and in the case of Queen & Country there have been dozens of artists, all with their own interpretation of Tara Chace. Some like Leondro Fernández go for ultra realistic, while others like Stever Rolston go for cartoon hyper-reality. This is a common occurrence in the event of sequels and eventual franchise in comic book culture: the characters get away from the original incarnation.

But wait, what about books written and drawn by the same creator? Terry Moore’s Strangers in Paradise is a good example of an ongoing series (it ran for 106 issues from 1993-2007) in which one creator maintained creative control. Even then, though, those 106 issues cannot be taken as a completely insulated text due to the nature of the evolving drafting process. It’s obvious as the series progresses that Moore veered the story in directions he had not originally intended. This is evident by how, on at least three occasions, there are flash-forward issues that depict possible futures (in one Katchoo and Francine reunite after a ten year absence; in another Katchoo dies before they reunite; in another they have a grown daughter who is the author of the comic book), futures that seem possible at that point in the narrative. The longer a storyline progresses, the more intentions change.

The Greek philosopher Heraclitus said, “You could not step twice into the same river; for other waters are ever flowing on to you.” Whenever a creator serializes a storyline (makes sequels, creates a franchise), there can never be continuity. That is not a negative, but simply a by-product of long-form storytelling. Take, for instance, the serialized nature of Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities, or more recently Stephen King’s The Green Mile: as both books were released in individual pieces before being compiled as a whole, there were inconsistencies along the way that had to be corrected in the collected edition. All ongoing comic book series, however, may get collected but never get corrected; they are continuous rough drafts that never get a chance for a second pass.

Even if a single writer were to go back and streamline inconsistencies across several volumes of trade paperbacks, those volumes will ultimately stay in rough draft form because they’re always being added onto by future storylines. More often than not, later issues in a series (perhaps written by different authors or the same author) loop back to earlier storylines and add new details or reveal secrets that change the very nature of the story. This is known as a retroactive continuity, and due to the common practice of retcons a text of a comic book series is forever malleable and subject to change.

So what about Watchmen, A 12-issue, self-contained graphic novel with one writer  (Alan Moore) and one artist (Dave Gibbons)? Surely that has to have continuity as solid as adamantium? Unfortunately, even Watchmen is subject to change. In 1987, a Watchmen RPG was released by DC Comics. It may have been endorsed by Alan Moore, but it was written by Dan Greenberg and Ray Winninger (with an essay titled “The World of the Watchmen”, co-written by Moore). Now there are rumblings on the horizon that DC wants to produce prequels. It’s in the nature of comic fans to want more, and comic companies respond in kind. Like Dr. Manhattan says, “It never ends”, so no text is sacred.

(Alan Moore) and one artist (Dave Gibbons)? Surely that has to have continuity as solid as adamantium? Unfortunately, even Watchmen is subject to change. In 1987, a Watchmen RPG was released by DC Comics. It may have been endorsed by Alan Moore, but it was written by Dan Greenberg and Ray Winninger (with an essay titled “The World of the Watchmen”, co-written by Moore). Now there are rumblings on the horizon that DC wants to produce prequels. It’s in the nature of comic fans to want more, and comic companies respond in kind. Like Dr. Manhattan says, “It never ends”, so no text is sacred.

Therein lays freedom. Dipping into Alan Moore’s oeuvre again, in the opening paragraph of “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?”, he states “This is an imaginary story…aren’t they all?”. Yes, every single issue. So when I sit down to read a comic book, I do so with the mindset that this is the first time I’m being exposed to these characters because this is the first time I’m being exposed to these characters. The artist may have drawn the characters before, the writer may have written them, and there may be proof of a shared history, but all one can hope for is to capture the Essence of the character. Even if I think I know the Clark Kent before my eyes, some future writer will add retroactive ripples.

So I say to myself: the ripples don’t matter. Continuity doesn’t matter. All that matters is the single issue you hold in your hands.

Also this week, we welcome the latest contributor to ongoing comics pillage, as Christopher “MGK” Bird joins the team:

UNCANNY X-MEN #1 (Marvel, $3.99)

UNCANNY X-MEN #1 (Marvel, $3.99)

By Christopher “MGK” Bird

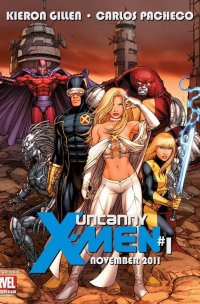

The critical zeitgeist surrounding this comic at present is that, despite being simply a continuation of the main direction UNCANNY X-MEN has been taking for years now, that it is new and fresh and exciting. This is not exactly true (unlike WOLVERINE AND THE X-MEN, a comic which takes equal portions of nostalgia and creative theft to generate something genuinely fresh and new, much in the say that Sam Raimi used to do back in the day before he became successful and boring), and a reminder that the majority of comics criticism comes from people who used to work at comic shops and have never really lost their mindset for flogging product on fanboys.

After all, advertising for FEAR ITSELF had Cyclops dressing up as Magneto nearly a year ago (and isn’t it a shame they never used that for anything other than trying to sell a pretty mediocre crossover?): the idea that Cyclops might be using fear to protect the X-Men is just not a novel concept. Granted, now he’s saying it out loud, and for superhero comics fans who can’t handle subtext (you know, the ones who read WATCHMEN and still don’t understand the point of the Black Freighter interludes, which is at least a third of them) this might count as revelatory. But it isn’t. Cyclops started ordering Wolverine to run black ops murder missions literally years ago. UNCANNY X-MEN #1 is just the next logical step on the staircase.

But, before one gets too negative, it is a good next step. Kieron Gillen and Carlos Pacheco are, respectively, a writer and an artist who each Know What The Fuck They Are Doing and that counts for a lot. Gillen actually manages to make Danger – who, lest we forget, has always been basically a third-rate retread of that one episode of “Star Trek: The Next Generation” where Data briefly considered being evil – interesting, which is probably the first time Danger has ever been interesting. (Pacheco does his best, but sadly Danger still looks like a pile of sex toys and PVC piping with glowy bits from TRON stuck on, which begs the question: why does an artificial being with the capacity to look like literally anything always decide to look stupid?) Gillen also manages to explain what the hell Hope’s powers actually sort of are, which is also nice since I didn’t know exactly, despite having read (I believe) every comic she’s ever been in, so that was nice.

On top of that, he also manages to give everybody smart, engaging dialogue without dialing up the cleverness to an unbearable level: Storm is appropriately earnest, Colossus properly solemn, and his Magneto strikes exactly the right balance between flamboyance and deadly seriousness. Gillen manages to update the entirety of Team Cyclops’ status in two pages, laying out exactly what everybody is doing and why they’re doing it. This is compressed, intelligent storytelling here. Other comics writers managing large casts should take notes on how Gillen does it. And finally, he manages to make Mister Sinister entertaining and threatening, which are two words I do not typically associate with Mister Sinister despite the fact that, unlike many comics critics, I love Mister Sinister’s name more than anything else about him. Traditionally, Mister Sinister is in bad comics, so it’s neat to see him in a good comic for once, and here he’s doing “villain with an agenda” to crazed perfection.

Carlos Pacheco is Carlos Pacheco, which means you know what you’re going to get: attractive, competent superhero art that serves the story well and doesn’t bother with being fancy because it doesn’t have to be fancy to get the job done. His art is starting to resemble Alan Davis’ more and more, and that is a good thing.

So: despite what many have said, this is not “new.” It’s not even particularly “fresh.” If you’ve been reading X-Men comics for the past couple of years, UNCANNY X-MEN #1 will be both unsurprising and fmailiar. But it IS exciting, and more importantly it is a damned entertaining comic book.that builds upon what has come before – and frankly improves on that. So, you know – it’s got that going for it.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

The Unexpected One-Shot (Vertigo, $7.99)

By Adam Prosser

It’s kind of an obvious idea if you think about it: why shouldn’t the comics company most associated with darker, edgier and more horror-oriented material put out a horror anthology comic? While a good quality comic of this type has been hard to find since the 70s, Vertigo has an unusually deep bench of writers and artists geared towards the genre, so this is the kind of thing that it’s hard to believe they didn’t put out 10 years ago. The result is an unusually consistent series of short horror stories, some of which actually manage to be creepy—something modern horror comics seem to have trouble with for some reason.

Probably the best story is “Dogs”, by G. Willow Wilson (a writer of whom I’ve become a staunch fan) and Robbi Rodriguez, which is disturbing, amusing, surreal and satirical in the way that the best “we woke up one day and the laws of nature had changed” stories can be. Less outright creepy, though still somewhat unsettling (and legitimately funny) is “Look Alive” by Alex Grecian and Jill Thompson, which asks the question: If zombies represent the mindless behaviours we cling to, what happens when said mindless behaviour involves being as un-zombie-like as possible?

Dave Gibbons’ “The Great Karlini” is a very old-school EC-style tale of murderous revenge, with rather more dynamic art than I usually expect from Gibbons, but sacrificing none of his famed narrative clarity. “The Land” by Josh Dysart and Farel Dalrymple is a classic “creepy folktale” told from the point of view of a Mexican immigrant, and while it skirts the clichéd “Ay Caramba” style of Latino-speak at times, it’s probably the most legitimately scary story in the book. “A Most Delicate Monster” by Jeffrey Rotter and Lelio Bonaccorso is another satirical story that takes an unusually thoughtful look at liberal guilt and cultural assumptions, behind a rather wacked-out premise. “Family First” by Mat Johnson and David Lapham goes the post-apocalyptic atrocity route.

The stories get a little weaker as you get towards the back of the book—“Alone” by Joshua Hale Fialkov and Rahsan Ekedal tells a pretty straightforward (though still effectively unpleasant) story of a hellish afterlife, and “Americana” by Brian Wood and Emily Carroll is a well-realized mood piece that doesn’t seem to have much of a point otherwise. The only real disappointment is the last story, “Blink…Le Prelude De La Mort”, by Selwyn Hinds and Denys Cowan; in keeping with the title, it (alone of these efforts) is merely a preview for an upcoming series, and fails to tell a coherent standalone story.

Still, this is a comic otherwise full of smart, effective stories, with a good value for your dollar. With this line-up of talent, there’s really nothing “Unexpected” about that at all.

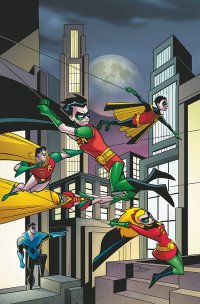

Batman: The Brave And The Bold #13 (DC Comics, $2.99)

Batman: The Brave And The Bold #13 (DC Comics, $2.99)

By Devon Sanders

Consistently, if one were to look for the truest versions of DC Comics’ characters, you had to go to the animated version. Animator/designer Bruce Timm with writer Paul Dini, along with many other talented folks, in 22 minutes crafted stories that recreated and more importantly, honored the things that made The DC Universe great.

Meanwhile, at any given time, comics-wise, Batman would be fighting a plague, an earthquake or going back in time to become a pirate.

That, friends, is Batman comics. For the longest time, some of, if not the best comics being published by DC were the comics based on the animated series. They were comics aimed with the kids market in mind but a funny thing happened somewhere along the line. They were being written and drawn by up-and-coming creators invested in telling some of the best stories they tell. Future Amazing Spider-Man writer Dan Slott told some of the best Justice League and Batman stories using the cartoon template as did future Kick-Ass scribe, Mark Millar with The Superman Adventures. Now, the one mainstay of it all was one of comics’ best working artists, Rick Burchett. With Batman: The Brave and The Bold #13 writer Sholly Fisch, Burchett returns to tell the tale of Robins and the results are everything great about Batman comics.

The mysterious Phantom Stranger walks into The Batcave holding the near lifeless body of Batman. Dick Grayson, Jason Todd, Carrie Kelly, Damian Wayne, Tim Drake and Stephanie Brown; the various Robins of different realities and timelines, gather as witnesses to the unthinkable. The Stranger has gathered The Batman’s greatest allies to work together for if they don’t… “BATMAN DIES AT DAWN!”

Writer Fisch crafts a life-spanning tale of Robins, past and present, showcasing the true importance of Robin to The Batman. He does so while noting exactly what makes each Robin unique; perfectly nailing each character’s voice and reason for being Robin. The results are simply fantastic. He just gets it. Especially his Damian… pitch perfect to a “TTT.”

And, kudos to Fisch for his truly inspiring and clever ending.

Artist Rick Burchett, while aping the B&B style guide manages to remain 100% himself. Burchett’s greatest asset is his ability to convey the needs of the story using the character’s body language. Burchett’s placement of the Robins on the page never suggests any sort of hierarchy giving the reader a sense of, despite these characters sharing a common name and similar costume, individuality. That’s something lesser artists could easily have mishandled but with Burchett it becomes a given.

Batman: The Brave And The Bold #13, with its honoring of legacy, is perhaps the truest DC Comic on the stands today.

(Sorry to say, folks. Word came down this week that DC is cancelling Batman: The Brave And The Bold with issue 16. Remember, with our every dollar, we get the comics industry we did or didn’t ask for.)

Mister Terrific Issues 1 – 3 ($2.99 each)

by D.S. Randlett

I don’t think that most writers really get atheists, even if they might be atheists themselves. I suppose that it might be understandable, given the tried and true formulae that most writers in popular media employ today. You know the basic outline: A kid doesn’t believe in Santa (but deep down, really wishes that he did), he then goes through a Christmas themed hero’s journey where he learns the true value of the holiday and, yes, how to really believe in Santa. This makes sense to kids (What kind of moron wouldn’t believe in Santa?), and it even makes sense within the context of a Christmas movie. It may not be the best analogy, but I think that this is how most popular story tellers are trained to deal with something like atheism. It’s a lack of belief, so there’s a void to be filled and room for the main character to grow, an illusion of depth in a story. This bias exists in DC’s Mister Terrific, and the myriad problems that are present in this series stem from it.

The problems begin with the nature of Mr. Terrific’s atheism. Like so much else in the series, it is incredibly ill defined. Did he turn his back on belief because of the tragic death of his wife, in which case he’s probably not really an atheist? Is it because of his rational nature? We don’t really know, and the story doesn’t care to give us any reasons to assume either alternative. But we do know that, through one of his experiments, he has a sort of epiphanic experience where he meets some sort of extra-dimensional ghost version of his unborn (never to be born?) son, who was of course in utero during the crash (Explained as the result of a haywire GPS system. Right.) that claimed Terrific’s wife. This “epiphany” inspires Michael Holt to become Mr. Terrific, and naturally leaves the door open for the character to doubt his atheism.

Issues 2 and 3 revolve around a confrontation with a character named Brainstorm, an opposite number sort of villain character. The book tries to make him into a sort of evil living social network (his forehead sigil is a similar to one of those wifi emblems you see everywhere, his blue skin evokes Facebook and Twitter) who fills his victim’s minds with random knowledge before they are ripe enough for him to consume, essentially making them go insane before he chows down on their intelligence. He is also able to control people’s minds, and he does this to get a crowd of people to spout various TEA party-isms at Mr. Terrific. A lot of what Brainstorm stands for and what he represents is obvious enough, but presenting him at this point robs him of any impact he may have otherwise had. We don’t really know who our hero is or he stands for here, so why is his confrontation with this new villain supposed to mean anything? What exactly are the stakes here?

The same problems that this title has in defining its main characters extend to nearly every aspect of the book, and this is compounded by its voice. We’re left with something that steals Grant Morrison’s crazy SF psychobabble and Joss Whedon’s snark, which ends up feeling old hat instead of fun. The writer seems to forget that Grant Morrison and Joss Whedon use their talents (or gimmicks, depending on where you’re standing) to add seasoning to something that’s they’ve taken care to flesh out, or at least have a concrete agenda for. Morrison can get away with some of his indulgences because he takes time to establish his characters and what they mean in the scheme of his stories before things get too crazy. His incomprehensible technobabble ends up not needing to mean anything, precisely because we know who we’re dealing with and where we stand in a central conflict. Mr. Terrific doesn’t earn these indulgences, and what we’re left with in Mister Terrific is a series of coincidences. Character motivations and actions happen solely at the convenience of the need for having stuff happen, and the crazy scifi stuff exists just for the sake of having crazy scifi stuff. The characters don’t feel like they matter, so nothing else does.

I doubt that this series will make it, which is on the one hand justice, but on the other a bit of a shame. Mr. Terrific is a character with a lot of potential to express something modern, optimistic, and fun. This current creative team seems to sense some of that, but is really struggling to define a voice for him, his villains, and his supporting cast.

1.5 out of 5

Carbon Grey Origins #1 (Image Comics, $3.99)

Carbon Grey Origins #1 (Image Comics, $3.99)

By Bart Bishop

World building is important in fiction. This process of developing an imaginary setting with a coherent history, geography, ecology, and politics (amongst other things) is a delicate task, as it has to be believable and authentic. This is common practice in the sci-fi/fantasy genre, and unfortunately story often suffers at the expense of the author’s sandbox. Note that there’s a difference between realism and believability: comic books, as a medium, suffer from realism, which is the attempt to ground fantastical events within a “this is how it would really happen!” framework. While that had its uses twenty years ago, the practice has become tired and depressing.

Believability, by comparison, is simple consistency within the context of the narrative. Carbon Grey Origins not only convinces of the consistency of the setting, but also resonates with imagination. This is a beautiful immersion into a brave new world. Carbon Grey Origins isn’t the most original combination of genre elements I’ve ever encountered, but it makes for an engaging read and amazing eye candy. Carbon Grey Origins #1 is one of two issues that serve as a prequel to Carbon Grey, a three issue mini-series (that first story arc, titled “Sisters at War”, was released earlier this year) which I did not read. With that in mind it’s an uphill battle for this issue to win my favor, being unfamiliar with the characters and the world it presents, but I’ve been convinced to not only check out the second issue but seek out the first volume.

Set in an alternate history in Mitteleuropa, an ambiguously German empire ruled by the Kaiser, it combines WWI iconography with steampunk and espionage. The focus is on twins born from a noble family: Mathilde and Giselle Grey. For centuries the Greys have protected the Kaiser. The first series depicts the twins as grown and dealing with the murder of the Kaiser, but this takes place years before. Divided into three short stories, the first focuses on the twins, the second on their father Gottfaust, and the third on a conman named Elliot Pepper. Although the first story has the most focus and is the most entertaining, the latter two have their pluses.

First of all, the cover (I got Cover B) is a beautifully rendered shot of the young twins in the midst of a shooting spree. This continues the long comic tradition of events on the cover that don’t occur within the issue itself. Still, it’s not out of character for Mathilde and Giselle, and their story is one of violence. Hoang Nguyen has a hint of photorealism with enough caricature to add to the story’s sense of hyper-reality. There’s a strong sense of energy and movement, along with an almost blank background except for the clouds of pink and orange around their heads that can simultaneously be halos or a mushroom cloud. Following that, the inside cover is a helpful bloodline, showing the characters’ (adult) faces, their names, and connections to each other. This is very helpful for a new reader, and integrated into the credits page slickly.

Part One, with script by Paul Gardner and art by Pop Mhan, has the twins as prepubescent, being secretly tested to gauge their skill level. In Mitelleuropa this involves sending a SWAT team into “the nursery” to rough them up, which results in a bloody rampage. It’s simplicity, but there are nice little touches of characterization and worldbuilding. Giselle’s prejudice against Mathilde’s dark hair, for instance, and the way the Kaiser is worshipped like a god. The sideways panels that show the Executive Committee’s notes on the twins is very cool, offering up insight into the characters (both the twins and their observers) with economy and style. There is a hint, however, of explanations and reverse-foreshadowing of events I’m not privy to, such as the explanation for Anna’s scar, the decision to separate the twins and “retire” Mathilde, and a discussion the Kaiser is shown having with an unidentified man. These bits of fan-service, however, do not detract from the core story. Gardner weaves dystopian future with medieval politics well, giving the cast an air of royalty and pompousness. Mhan has clean linework and a cinematic use of angles, close-ups and cut-aways. He also doesn’t over-sexualize any of the female characters (the majority of the cast), which is much appreciated.

Part Two is scripted by P. Tuinman with art by K. Evans, and although a short read I appreciate the evoking of daily newspaper strips. The art is suitably old fashioned, giving five pages a sense of wonder and mythmaking, although I seriously had no idea what’s going on. It reads like an antiquated superhero origin, with Gottfaust gaining super strength from a “falling star” and subsequently saving the Kaiser from attacking wolves. The narration is like something from an old radio serial, all pomp and circumstance, and there’s a sense that this is intended propaganda from the office of the Kaiser. Which is fun, but makes me wonder how “real” it all is to the fictional universe that Gottfaust occupies.

Part Three is scripted by Paul Gardner with art by Joffrey Suarez, and is the least accessible of the bunch although the story itself is rather straight forward. Two officers meet in a bar to discuss Elliot Pepper, a U.S. con man that has been causing trouble in Mitteleuropa. Again there’s the feeling that I should know who Pepper is, or that he played a substantial role in the original series. Without the benefit of that knowledge I’m left wondering what kind of relationship the U.S. has to Mitteleuropa, a nation that seems to be Germany if it conquered most of Europe. What state would the U.S. be under those circumstances? The map was much appreciated, giving Mitteleuropa authenticity and playing into my subtle OCD tendencies. I’m the kind of guy that reads The Lord of the Rings and tracks Frodo’s quest on the map. The artist has a real skill at facial expressions, running the gauntlet of emotions here and giving each character distinct features (apparently there’s even black women in this fictional Europe of a hundred years ago, although she is a prostitute). The twist at the end was a nice if obvious touch, but what I take away from this short story is the burnt out landscape. Mitteleuropa has been desecrated by war, but the little people go on living while the Greys and the Kaiser reign at the top.

I’m intrigued. The pinups in the back alone hint at a concept rife with possibilities. I admit a part-Darth Vader Red Baron has me excited, and the shots of the adult Greys in battle gear are quite striking. There is that risk, however, of coasting entirely on a concept. There’s also the risk of playing into the “bad grrl” genre, with T&A and big guns substituting for storytelling. Luckily the creative team of Carbon Grey look to be avoiding those pitfalls, and have established a setting worth revisiting, with class, politics and war all crashing into a theme of control. Each story revolves around the human spirit somehow managing to triumph over the system, even if it’s a small victory. This union of the human spirit is universal and captures empathy and sympathy well, even in a world of killers and diplomats.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

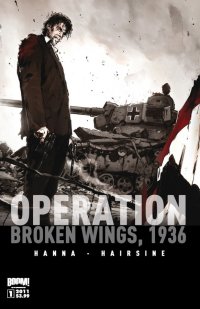

Operation Broken Wings, 1936 (Boom!, $3.99)

By Jeb D.

Far as I can tell, this comic is part of a French series (called Le Casse), and it seems likely that this particular volume is getting a U.S. release because artist Trevor Hairsine is a name that can be marketed to American comic fans. I suppose that’s as good a reason as any, when the result is a satisfying story of wartime espionage and action.

Writer Henrik Hanna lays out an effective introduction to his tale, cannily revealing only enough to keep the reader hooked. The book opens with a nameless narrator in a filthy prison, musing on the existence of hope, taking us from there into what we presume will be the story of how he got there. In 1936 Germany, the narrator kills an old man and his son: is he on a military mission? If so, is he working for or against the Nazi regime? Is he serving an old vendetta? These questions come up during a subsequent interrogation scene, and while we get a few hints (our protagonist may have saved Hitler’s life in 1923), what we’re mostly shown is the dark and bloody fragments of his story, leading up to the launching of another murderous mission. Translator Edward Gauvin does a superb job of keeping the narration and dialogue clean and clear, seemingly true to the period, while retaining some of the dark poetry of the noir narrator (“One last ray of hope that this cell didn’t swallow… God never comes down here”). The book’s nineteen pages are well-packed with action, which Hairsine handles deftly in his “When-I-grow-up-I-wanna-be-Bryan-Hitch” mode. Even better is his depiction of the period German setting; it feels lived-in and convincing. If this is an example of the kind of storytelling typical of this French series, here’s hoping there’s much more to come.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

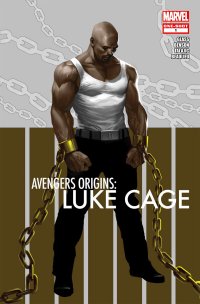

Avengers Origins: Luke Cage (Marvel, $3.99)

Avengers Origins: Luke Cage (Marvel, $3.99)

By Jeb D.

For all those out there (both of you) who have been wondering when and how Brian Bendis developed his man-crush on a big, burly, bald black man, here ya go. Writers Adam Glass and Mike Benson offer a 32-page recap of the Luke Cage chronicle. For something that is basically a book-length extension of an introduction page, the story moves well enough, and retains good focus. As someone old enough to remember Luke Cage’s “Hero for Hire” debut (and who, parenthetically, started to lose interest when that aspect of the character was jettisoned), I can say that they do a decent job of recapturing the roughness of the 70’s blaxploitation that inspired his creation without tipping over into parody: it’s more Jackie Brown than Black Dynamite. Artist Dalibor Talajic has a nice urban style, with exceptional detail in the facial distinction between the various African-American characters (not a strong point for a lot of artists), and he’s flexible enough to give nods here and there to the more superhero-y styles that we associate with Cage’s Avengers era. Sweet Christmas!

I should tell you that there is also a 6-page preview of the upcoming Jeph Loeb / Ed McGuiness X-Sanction series. I’m sorry.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars