The greatest of films that exist to pay tribute to others are, invariably, themselves great examples of the genre, style, or aesthetic to which they pay tribute. This is largely because any filmmaker who can successfully comment on and deconstruct a certain kind of cinema likely has not only a genuine love of that genre, but an understanding of how and why the conventions of that genre work.

The greatest of films that exist to pay tribute to others are, invariably, themselves great examples of the genre, style, or aesthetic to which they pay tribute. This is largely because any filmmaker who can successfully comment on and deconstruct a certain kind of cinema likely has not only a genuine love of that genre, but an understanding of how and why the conventions of that genre work.

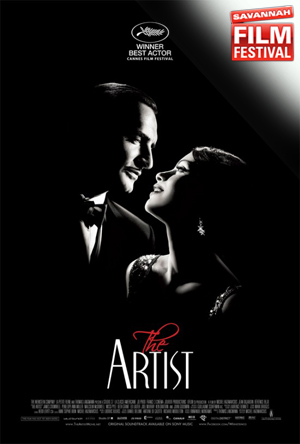

With The Artist, director Michel Hazanavicius demonstrates that he’s not just intimately familiar with every instrument in the toolbox of the silent filmmaker, but that he’s actually capable of picking them up and putting hammer to nail to build one as they did. That’s to say he doesn’t just love silent film, he understands it. He feels the very specific, very universal, and very enduring charms of the films of the 1910s and 19020s, charms that he has deftly exploited to make one of the most satisfying, uplifting, and beautiful films of any genre in many years. It is also well and truly a silent film that, save for the slightest and briefest of metatextual flourishes, could have easily passed for a contemporary film in the era it explores. And yet, I’m certain The Artist could successfully win over even the most black-and-white adverse audience members, and would have no problem entertaining even those with the most massive deficits of attention span. Its themes are universal and yet timely, as we can all identify with the flipped coin of progress that doesn’t always land on the side we called.

Louis Lumiere famously once said of Cinema, a form he and his brother were sort of simultaneously inventing in France as Edison was refining his discoveries in New Jersey, that it was a medium without a future. A few short decades later though, it already held the cultural sway to create, and tear down, monumental icons of celebrity. The Artist tells the story of such a celebrity, George Valentin, who holds sway over Hollywood and America itself after a long run of silent films in which he and his adorable little terrier save the day and all that. He has the wealth to own a palatial estate, the power to re-cast major motion pictures on the fly in front of a studio head, and a smile that simply owns an audience. He’s played to utter perfection by Jean Dujardin in what I would call a “command performance,” except that you can’t just performe this kind of bigger-than-life charm, you must simply own it. He is a true silent film star that appears to have control over every individual muscle in his body, and demonstrates the kind of vaudevillian sensibility that early film was known for capturing, and yet it’s filtered through a sense of subtle artistic control that earns the hero, and the film, the title of “artist.”

The winds of change cease blowing for no man though, and George Valentin finds himself quickly usurped at the box office by a beautiful young woman, Peppy Miller, that he himself had a part in discovering. The two nearly become embroiled in an affair, but instead circumstances drive them apart and George finds himself suffering the blows of a crashed stock market and an almost overnight Hollywood retooling for talkies. While George stubbornly plows ahead with his great silent masterpiece, Peppy Miller becomes the demure toast of Hollywood, riding on wave of success inversely proportion to George’s steady decline. Berenice Bejo is a revelation as Peppy; her exuberant, masterful handle on the charms of a Depression-era starlet is uncanny. It’s easy to see why Bejo and Dujardin have become a sort of dual-muse for Hazanavicius.

What follows is a classic tale of loss, redemption, jealousy, and love captured with an incessantly clever and dynamic eye. The sublime engineering of the film is at once perfectly true to a long-disconnected and unrelatable mode of stoytelling while being perfectly accessible to a contemporary viewer. A symphony of music, performance, editing, and shot design all play out without ever winking at the audience, though it quite often winks with them. Supporting players with familiar faces like John Goodman and James Cromwell are woven into the film so gracefully that they barely cause a ripple, much less a disruption of your utter belief in the film being truly of its time.

Any film fan has a soft spot in their heart for the mise en abyme of film’s that are in love with the idea and/or history of film. That said, there’s always a danger that such films can cross the line from passionate and clever to pedantic and overbearing. Hazanavicius steers clear of any such problems, managing to integrate abundant references to classic films as well as a single brief, earned scene of self-awareness without ever crossing that oh-so-thin (often very permeable) membrane between celebration and masturbation.

“All the world’s a set” Hazanavicius seems to say, suggesting that we are all artists struggling to stay relevant, to not blow our second chances, and to find our true love. Fortunately for us, The Artist (and its metaphysically recursive final shot) goes on to suggest that movie-magic doesn’t just happen on the big screen, but can happen in our lives if we let it.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars