BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE!

BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE!

STUDIO: Warner Bros. Home Video

MSRP: $34.98

RATED: R

RUNNING TIME: 132 Minutes

SPECIAL FEATURES:

• "Freedom! Forever!" behind-the-scenes featurette

• Production design featurette

• Historical documentary on Guy Fawkes

• "England Prevails" comics history featurette

• Cat Power montage

• Theatrical trailer

The Pitch

"1984 meets The Matrix. No dangerous artificial intelligences; just right-wing nutjobs!"

The Humans

Hugo Weaving, Natalie Portman, John Hurt, Stephen Fry, Stephen Rea.

The Nutshell

In a near-future

Hadouken!

The Lowdown

I can’t really get this review started without considering its iconic protagonist. The grinning mask, the throwback attire etch themselves into the visual imagination, and carry along with them a extraordinary character.

A fair amount of ink and electrons were wasted around the time of V for Vendetta’s premiere on the subject of whether

"I fight to free us all from the strictures of good taste."

There is a complicated duality to the character of V. The narration by Natalie Portman, which bookends the film, speaks of how V became a symbol, but she will remember him as a man. I suspect the film would have failed completely without these audience-addressed words, and the actions that support them — not because it would have been a bad film, but because the sympathy that is absolutely vital for a modern audience’s connection with V would have been obscured beyond the point of effectiveness. He is a symbol, by his own claims, in a film obsessed with semiotics. Symbols are difficult to identify with on their own.

That’s one of the reasons the filmmakers were as lucky as they were to get Hugo Weaving cast in the role of V. He has always been a man of fantastic line delivery, the sort of actor who tastes every word before letting it go from his tongue. He perfectly captures V’s erudite speeches, the rehearsed politics that he shares with Evey and the world; no lesser are his emotional dialogues, which melt right through the ever-present grinning mask, seeming to change its shape.

I’ve got an analogy for that, if its all a bit too abstractly poetic. Have you ever watched a foreign film with subtitles, and then gone over its dialogue in your memory afterward? Often, I find that my brain has melded the words read with the words spoken, so I recall the actors speaking in English, even though they never uttered a word of it. In a similar fashion, when recalling much of V’s dialogue, his mask seems to change form in my memory, as my brain melds the emotion with the physical perception.

I am on drugs, yes, but they’re prescription.

All is forgiven, from the geeks’ point-of-view.

Allow me to talk forever, here. I can’t move on without praising the remainder of the cast. Natalie Portman suffers through an amazing, harrowing transformation so convincingly visceral that it may make you sob with relief when it’s over. Stephen Fry plays a kind man hidden behind a facade of political support, whose inner tensions manifest in an admirable dry humor. Stephen Rea, as detective Finch set to the pursuit and capture of V, does a lovely job of portraying a beaten man whose cracks have started to widen, and who is beginning to fall apart. Finally, John Hurt, is twice removed from being a character — he is a figurehead of a symbolic order — but manages to delivery his short-sighted, scathing lines with a desperate fire that calls up all sorts of indignation from the audience.

I’ve been very focused on the big ideas, the ones large enough to crush a country, so far, which conveys the impression that this is an oppressive movie. That’s not the case. This is a Wachowski-scripted flick, which means there are popcorn elements included. Decently-choreographed action scenes pepper the drama, as do moments of levity, of pleasant sentiment. I admire the balance of tone that director James McTeigue achieved here. Nothing feels forced. V cooks an eggie-in-a-basket for Evey while wearing a pink apron. He fences dramatically with an empty suit of armor while watching The Count of Monte Cristo. And, in one of my favorite scenes in the whole movie, Stephen Fry’s television personality creates a terrific send-up of variety-show zaniness, lampooning Hurt’s High Chancellor, and setting up the weighty second half without hardly even seeming to try.

"Two hairs out of line on the left sideburn, sir."

All of this is in service to the story. The screenplay lacks the meticulous cohesiveness of Alan Moore’s writing on the source material, but it does preserve at least a bit of the constantly recurring themes, the circular nature of scenes which seem to reach back to previous ones while at the same time stretching toward the following.

The balancing between dark and light material wasn’t the only challenge handily overcome in the screenplay; the Wachowskis also managed to translate the disturbing parallels between V’s personal vendetta and his political one. The character of V, a superhero of sorts, has a terrifying origin story, and many of his actions in the first half of the film are oriented on repaying the people who created him. V’s amorphous focus calls into question the perceived justness of his actions against the government, at first. It is redeemed in two ways: first, its presence humanizes V, setting up the duality between symbol and man which is the emotional core; and second, it dovetails so neatly into his plot against the government that the seams are only visible in retrospect.

That plot deserves a bit more discussion. I said before that V is an unapologetic terrorist. He is convinced of the rightness of his actions, but it is incredibly important to note that he never once takes pride in them. The only thing in his world that summons up his pride is Evey. Their relationship is wonderfully nuanced: warm, cold, and expansive. Without it, V’s actions would seem more heartless, yes, but what’s more they would seem less important. His relationship with Evey doesn’t justify his actions. He doesn’t seek justification, within the context of the film or without. Instead, it casts them as a gift to her. It’s not a gift that she has asked for. V doesn’t need that kind of purpose; it’s not purpose that he lacks. It is inspiration.

Daily Show 2020

I don’t want to come off sounding as if I am justifying V’s actions, either. I’ll keep repeating that it’s not only a silly proposition to do so for a film like this, it’s entirely unnecessary. Fiction, as Alan Moore has said in interviews and which words have been given to Evey in the film, is a tool for uncovering the truth. Fiction of this dystopian stripe is often an exaggeration of current events, cautionary tales that describe what imagination calls up for the future. Actions are exaggerated, as are politics, social mores, repercussions.

The question becomes not whether an audience should approve or disapprove of V’s actions, but whether the truth conveyed thus is a worthy one. In a line, another exaggeration, which (with good reason, I think) became something of a tagline for the film, V sums up this truth with: "People should not be afraid of their governments; governments should be afraid of their people." This is a truth that absolutely deserves airing in our current political climate, though it is purposefully overstated. Here in

The truth behind V for Vendetta’s exaggerations is an important one.

I wonder how long it will be before somebody replicates this in Oblivion.

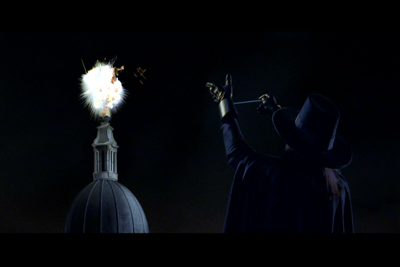

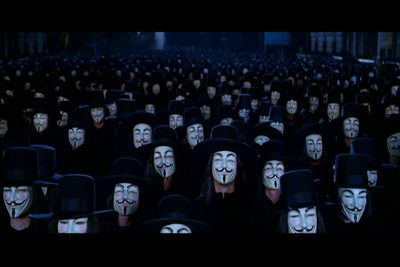

Returning to the level of the film itself, I feel the need to comment on the grand finale. In a move that deviates quite a bit from the source material, the perspective of V’s struggle is widened. Thousands of English citizens storm

Trafalgar Square, each wearing a copy of V’s mask and costume, while V passes underneath them in his explosive funeral bier, on a course for the Houses of Parliament. Broadening the fight at the end is entirely in keeping with the way the message has been presented in the film. The fight is no longer a personal vendetta, but a universal struggle. It removes some of the feeling of single-minded propaganda which builds throughout the first two acts, which is entirely appropriate. Propaganda is a useful tool, like fiction, but this is a modern narrative, and asks for the audience’s participation. It’s not an entirely successful conclusion, in my opinion. It robs V’s sacrifice of some of its import by widening the focus, and it loses the vision which Evey uses to carry the film in and out. She claims it’s a story about a man, but at the end it becomes a story about an immortal idea.

Running up to that point, though, V for Vendetta is a widely palatable adventure. It follows many of the arcs of mystery, conspiracy, and man-with-a-mission tradition, but it does so with a wealth of substance, pathos, and humanity that no recent film in its genre has come close to equaling. It’s a compelling argument for freedom, because nothing is perfectly resolved, and the gaining of freedom is never fully satisfying. Full of big ideas, big drama, and big explosions, it’s a film worthy of equally-proportioned accolade.

The Package

Speaking from the level of educated consumer, I’ll say that I’m a little disappointed with the video and audio quality of the disc. We get only Dolby digital surround tracks, which have a lot of punch, but not as much depth as the DTS track that could have been. The explosions and accompanying "1812 Overture" are suitably dramatic, but smaller things like rapid British dialogue and ambient sounds are lost in a bit of mud. The visuals are mostly clear, except for when trying to match V’s black costume against any black set that was added from green screen. V stands out with ugly purples instead of being fully shadowed. The effect is distracting.

The disc authors didn’t go whole-hog on bonuses here, but the two discs do offer plenty of interest. The first disc features a behind-the-scenes featurette which is heavy on information and light on marketing, thankfully.

There’s no moshing at the triumph of the common man over adversity.

Digging deeper into the making-of, the second disc carries a featurette on set and production design, covering sculpture, mask-making, landmark destruction, and the organization required to close off Trafalgar Square entirely for three consecutive nights. Much is made of the (successful) attempts to create a future world that looked dark, like an oppressive Victorian throwback.

In the peripheral material, there’s a documentary on the historical figure of Guy Fawkes, his foiled plot to blow up the Houses of Parliament, and the political climate that brought about that Catholic rebellion. It’s fascinating, and features interviews with a number of keen-eyed historians. It’s not strictly tied to the themes of the film, but the parallels between the 17th century monarchy and the film’s totalitarianism are worth a few minutes’ rumination.

Alan Moore may have gotten his name off the credits (which is sad, since this is the first adaptation of his to actually work as a film and be respectful to its source material,) but he does get discussed in a wonderful little featurette on the history of comics for adults. Through interviews with industry veterans — such as Karen Berger, the woman who also helped to usher in Neil Gaiman’s tremendous Sandman series of comics — the history of the Comics Code Authority is examined up through its dismissal, which made room for the glorious eighties, when Frank Miller, Alan Moore, and others made their incalculable contribution to the legitimizing of modern comics as an art form.

Other than that, the second disc contains a Cat Power "montage" (at least they didn’t call it a music video) of scenes from the film set to Chan Marshall’s beautiful cover of Lou Reed’s "I Found A Reason." There’s also a theatrical trailer. Huzzah!

9 out of 10