Earlier this year I visited the Newark Airport location shoot of United 93,

Earlier this year I visited the Newark Airport location shoot of United 93,

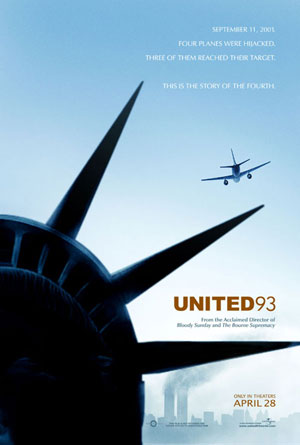

Paul Greengrass’ reconstruction of the events on one of the hijacked

planes on 9/11. One of the people I was able to speak with that day was

Lewis Alsamari, who played one of the hijackers. There had been a

hassle getting Lewis into the country because of his background – he

had once been in the Iraqi army.

Lewis has recently made

headlines as he’s been currently barred from returning to the US for

the Tribeca Film Festival premiere of United 93. "It

would be so disappointing not to be able to go because I still have not

seen the film. I have only seen footage and it would have been amazing

to be in New York for the premiere," he told the Evening Standard.

Alsamari’s

service in the Iraqi army in the early 90s makes his visa process a bit

more complicated than most people, and it was this issue that held him

up last time. When he was in New York last he shared with me some of

the details of his escape (some had to remain off the record for

various reasons, but I can tell you that the full story of Lewis going

AWOL and escaping to Britain will one day make a gripping book).

Q:

The war on terror has opened up more Arab and Muslim roles in film, but

they tend to be bad guy roles. I asked Alexander Siddig about this at

the Syriana press day, and he said that it’s good to have more roles in

general. What’s your take?

Alsamari:

In the beginning I was fascinating about romantic roles, but in reality

I kind of like playing the villain. I’ve done so many of them now. I

enjoy it more, it’s more serious and dark.

Q: So you don’t mind that when you walk into a casting call, they’re thinking ‘Here’s the villain?’

Alsamari: If

you’re an accountant do you mind doing tax records for a government

office or a public office? It’s a job. What’s more important than the

role itself is the quality of the content. No matter how good the role

is, if the content is shit you’re working with bad ingredients and you

can’t cook well with bad ingredients.

Q: You were in the Iraq army. Can you talk about what happened, how you ended up leaving, and how you came to the UK?

Alsamari: I

came to the UK at the age of 6. We left the UK at the age of 13; my

parents split up and we returned back to Iraq. It was very good to be

an Iraqi citizen at that time; the Iran-Iraq War had just finished. At

the age of 18 I didn’t complete my high school and I didn’t go to

university then, and so they wrote to my military unit in Samarra and

they told me I needed to be in service. I went to three months training

in Baghdad where they prep you up – you get your boots, you get your

uniform. After that, after three months of training they ship you to

your permanent unit for three years or one and a half years depending

on what kind of service you do. It’s three years if you haven’t

completed a degree or one and a half years if you have. I was shipped

over to Al Amari, which is in the south of Iraq on the motorway stress

between Baghdad and Basra. It’s very close to the Iranian border and

there are a lot of marshlands. I was in infantry. There were about 200,

250 soldiers there.

I

served for about a year and I was giving all my wages to my commanders

as bribes so I could have extended leave. I trained in AK-47s,

Brownings, Colts. We had basic training, crawling through barbed wire…

Q: What was it that made you want to go AWOL?

Alsamari: I

didn’t want to be in Iraq anyway. It was like torture for me before I

went to the army because I grew up in the West and my whole mind was

the West. I used to worship  Michael

Michael

Jackson and all that kind of stuff. I lost all my hair, I had these

terrible migraines, I just wanted to leave so much and go back to the

UK. So I decided to flee.

My

uncle over there was helping me out – he was getting forged documents

for me to leave the country to Jordan and then from there find my way

to the UK. On that particular day I was on my monthly leave, I was

stopped and accused my pages of being forged and I was sent back to my

unit.

Q: And that was when you got shot.

Alsamari:

I got shot as I was leaving my unit. I was shot in the leg – an AK-47.

It was rebounded bullets from an old truck, otherwise my leg would be

shattered. I still have the marks on my leg.

My

uncle was waiting at the border to Jordan. Some tribesmen helped me

cross into Jordan. I took a flight to Yemen and stayed there for a

year. I saved up a lot of money and bought a fake UAE passport and used

that to go to Malaysia. I entered Malaysia illegally and stayed for

four days and booked a flight into London, which is what many refugees

are doing. I arrived in London on December the 4th, 1995 crying my eyes

out. I was granted asylum and permanent residence and have been there

ever since.

Q: How did you get into acting? Was it something you always wanted to do?

Alsamari: The

roots of it is when I was 7 years old and I sat on my dad’s lap in

Manchester watching an Omar Sharif film and I said to my dad, ‘Can I be

like him?’ He smiled and said, ‘Of course you can, as long as you don’t

do all the naughty bits.’ He was very religious.

That’s

where it stemmed from. When I came back to the UK I started working in

finance, and then I had to get a degree to please my parents, so I went

to get a Law degree. Two years into my degree a friend dragged me onto

the set of one of the TV series there as an extra and I really liked

it. I only did it a couple of times and then I decided this was what I

wanted to pursue.

Q: You had a hard time getting into the US?

Alsamari: I

wouldn’t say it was a hard time. I would say it was a long-winded

process for me. I think the problem was that we should have applied

earlier because of my military service and my documents as well, the

documents they issue to refugees which cause more of a problem than an

Iraqi passport does – if they wanted to get rid of me, they don’t know

where to send me. The UK does not give guarantees that they will take

me back, whereas an Iraqi passport they would. It was more of a matter

of clearance with security agencies here about my military service.

Q: Do you have any plans to go back to Iraq now that things have changed?

Alsamari: I don’t plan to settle there, to be honest.

Q: But to visit?

Alsamari: I haven’t visited yet.