Steven Soderbergh is one of the most important directors working today. You just can’t argue that. His Sex, Lies and Videotape kick started the indie film revolution in the 80s, and since then he and his peer Richard Linklater have gone on to define the ultimate modern career path, balancing thoughtful, intelligent and personal films with major blockbusters and broad Oscar fare.

Steven Soderbergh is one of the most important directors working today. You just can’t argue that. His Sex, Lies and Videotape kick started the indie film revolution in the 80s, and since then he and his peer Richard Linklater have gone on to define the ultimate modern career path, balancing thoughtful, intelligent and personal films with major blockbusters and broad Oscar fare.

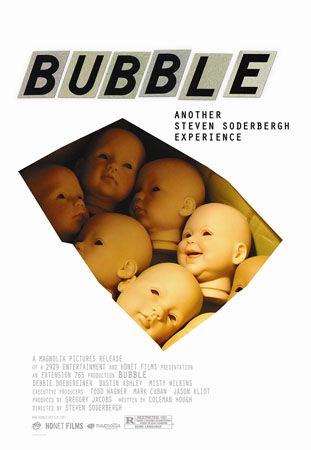

Soderbergh isn’t done changing paradigms. His newest film, Bubble, is a small movie shot in Ohio and West Virginia with a cast made up entirely on non-actors. The story follows the friendship of doll factory workers Martha (Debbie Doebereiner) and Kyle (Dustin Ashley) when a third person is introduced – attractive young Rose (Misty Dawn Wilkins). This triangle eventually comes to a head in murder.

Bubble isn’t just experimental because of the cast – it’s also testing new waters in film releasing. The movie hits 40 theaters tomorrow, and you can watch it tomorrow night on HDNet (if you get that channel) at 9 and 11 PM EST. The DVD of Bubble comes out Tuesday – you can pre-order it now at http://www.bubblethefilm.com/.

Q: When you came to this project, what was the first thing that came to mind? To do a murder mystery? Or was it just a script that came to you?

Soderbergh: No. Well, I knew that I wanted to get out of town, cause I think it’s good to travel, and the initial idea was just a triangle. Coleman Hough and I had been talking, and I’d sort of identified her as somebody that wanted to help me on this first one. I watch a lot of true crime stuff on TV, and a lot of those take place in towns that you don’t normally see, which is fun. City Confidential – I love that show. Very sad that Paul Winfield is no longer with us.

So that was all sort of mixing around, and then this idea of what they do for a living grew out of my wondering… you go to the movies and it seems like—lawyer, doctor, advertising—it feels like there’s four jobs that you’re allowed to have in a studio move, and that seemed sort of unfair, so I thought well, let’s look for an interesting job. I was interested in manual labor, especially since I’ve had dead end jobs before, but I’ve never had an all-day manual repetitive labor job. I don’t know that I can do it. I don’t know how they do it, people that literally just sit there and do the same thing for eight hours a day, so I said I wanted something like that. Coleman’s the one who found the doll factory. Apparently, there are three factories of any real size left in the U.S. This is one of those businesses that’s gone overseas, and two of them are in Bel Prix, Ohio.

Q: How did you cast Debbie as Martha? She had been working at KFC, right?

Soderbergh: Our casting director, sort of embedded herself ahead of us, and went around, asking people if they’d like to be interviewed. We didn’t do an advertisement/cattle call thing. She knew kind of what we were looking for and would approach people and ask if they would come and be interviewed. She was in the drive-thru at the KFC. She’s normally a very healthy eater, and just this one day she was jonesing for KFC, which is much more my speed, and she’s sitting there and she hears this woman berating these teenagers that worked there, like telling them that they were not doing something right. [The casting director] leans her head over, because at first she just hears the voice, and she sees Debbie, and she immediately pulls out of the lane and parks and goes into the restaurant and says, “Would you like to come down and be interviewed to be in this movie?” For Debbie, you can imagine what an odd occurrence this was, and then she comes down and she interviews, and then of course, she hears that she’s got the part, and nobody at KFC believes her, and they think this is all some Martha-like psychosis. She has to go ask them for four weeks of leave so she can go star in this movie.

The guy who got the most flak was Decker Moody, who plays the detective, whom I think is spectacular. He said that the people at work were relentless, they just wouldn’t stop teasing him. They just thought that this was a classic case of how smart can these Hollywood people be if they’re putting you in this movie? He was incredible. I mean, I can watch him for hours.  Q: When you’re working with a cast like this who are not actors, how does that make your job as director different? How do you work with them differently as opposed to when you’re working with Brad Pitt or George Clooney?

Q: When you’re working with a cast like this who are not actors, how does that make your job as director different? How do you work with them differently as opposed to when you’re working with Brad Pitt or George Clooney?

Soderbergh: It’s interesting that some people have asked me… this came up in Toronto, somebody asked if I was exploiting these people, and I said, “Absolutely. Of course, I am. I’m also exploiting Brad Pitt.” I mean, that’s the deal. I’m getting something and he’s getting something, and I could argue that I’m getting more than him.

In this case though, by the time we started shooting, we tried to explain in as much detail as we could how this was going to work, and we’d also been talking them to a lot, because all of these stories that they tell in the movie are theirs. We were trying to fill up as much as we could with these personal stories. I think they were a little anxious until their first day of work, and then they realized… They just didn’t know what was expected of them, and then once we showed up and they realized that all I expect from you is for you to be yourself, as much as you can. There’s no wrong answers. It’s not a test. Then they really relaxed. I definitely saw a shift in Dustin from the beginning of the movie to the end, just in terms of how he was relating to us and to the crew. He changed. That story of him leaving high school because of this anxiety disorder, that’s true. He’s not coming to the premiere tomorrow night. There are too many people. He’s sending his girlfriend with a camera to document it, but at the same time, it was really fun to see him open up, because we sort of shot in chronological order. He was having fun. You could see him joking and talking to the people at the end of the shoot, which would have been unthinkable the first day.

Q: How much have you been in touch with them since you’ve finished, and how much do you plan to, since this is the kind of thing that would change people’s lives.

Soderbergh: Debbie and I e-mail every once in awhile. I’ll let her know this is happening or like I e-mailed her after Venice and New York just to tell her how the movie went over. They’ve been mostly in touch with Coleman, they’ve been in touch with her a lot, and she sort of forwards me stuff or she’ll tell me, because I talk to Coleman a lot and she’ll tell me what’s going on. They seem to have a very healthy attitude about it. I mean, everybody who worked on the film owns a piece of the film, so if something good happens to the movie, this will be a great little annuity for them.

I know Debbie looked at it as just like camp. She was taking pictures all the time. She said, “I can’t believe I’m going to walk into a video store and my name is going to be on the box, and this is just so exciting.” She had a great attitude about it.

Q: Do any of them have any aspiration to continue in acting?

Soderbergh: I don’t know. I didn’t want to discourage them, but it’s hard if you’ve seen what happens to people who go into acting, it’s hard to sit there and go, “You should really pack up your car and move to Los Angeles.” That’s not a responsibility that I would want, but I thought they all did wonderfully well, and if somebody wants to give them an opportunity to do something, why shouldn’t they take it?

Q: Outside of your directing, were they provided with an acting coach or did you approach directing them differently than you would another actor?

Soderbergh: Here’s one thing I’ve learned. The more that you can talk to an actor in terms of just physicality, the better off you are. Whenever you get onto “What you’re feeling here is… “, if you can be really specific about something physical, it’s very helpful to them, because it takes them out of their head. What you don’t want is an actor who’s in their head, so more often than not, the physicality of the scene what was really crucial.

Q: What direction did you give the young factory workers when they meet for the first time?

Soderbergh: Well, I just told Misty to stare at him. He’s the only person that you’re interested in this room. Stare at him, and then of course, we shot that side of it, and she came over and said, “He won’t look at me.” And I said, “Don’t worry, when I turn it around, I’ll make him look at you.” The great thing about casting Dustin is then if I go to Dustin and I go, “Dustin, I want you to stare at Misty and don’t look at anything else,” as soon as we turned the camera on and he started staring at her, his cheeks went just completely red, because it’s so hard for Dustin Ashley to stare at a girl without looking away for sixty seconds. It’s like physically hard for him to do that, because he’s so shy, and he just flushed, and you just can’t put a price on that. That’s just luck.

Q: So you’ve signed on to do five more movies as part of this deal. Have you thought about what you want to do next?

Soderbergh: Non-actors, different locations, stories set hopefully all around the country, so it will be a quilt of movies that are sort of Americana in one way or another. But yeah, same idea. I know what the next two are going to be, and I’m at the stage where I know them well enough to where once I decide where to do them, I can go to the town. I know what the number of characters are in the movie, so we can start the process of embedding ourselves and building the story. It’s just a matter of when I’m going to have another window of opportunity.

Q: Do you build these films more organically?

Soderbergh: I hope that the development process on everything we work on is somewhat organic, or at least not forced, but in this case, the flexibility of the way that the movies are being financed and produced allows you a lot more freedom than you would normally. I mean, it’s difficult on movies of over a very small scale to get somebody to basically just let you go and figure it out. It takes a company like this. All we had was a three-page scene breakdown with a description of who’s in the scene and what happens, and that was it, and there are a lot of people who don’t want to finance movies on that basis, and I understand it, but [producers] Todd and Mark know me well enough to know that I’m a big believer in parameters. On the one hand, I have a lot of freedom. On the other hand, there are certain economic boundaries that I have to sort of accept. I feel like there have to be lines.

Q: Your career has been so interesting because you bounce around from small, experimental films to big blockbuster films. In the last few years you’ve really refined that balance. Forgive me if this question is indelicate and or rude, but you’re going back to the Ocean’s 11 well again for Ocean’s 13 – is that a case where you really felt like you had a story to tell there, or was it just, ‘I want to go on making interesting movies, so I had better make some money’?

Soderbergh: No, I love making those. Both the second one and this one were generated by me saying I wanted to do another one. Nobody asked – certainly nobody’s asking for this one. I just wanted to. I had another idea and I went to everybody and said, ‘I have another idea,’ and everybody said fine.

They’re fun for me. I just get to play as a director. I get to do things in those movies I can’t do anywhere else, so they’re fun for me. They’re not easy, in the sense that I work hard on them. You really do have to show up everyday with ideas to keep things moving along. And sometimes that’s hard, because there are days when you don’t have any ideas. But it’s also difficult to find material that is commercial that doesn’t make you feel bad in the morning. These are great opportunities for me.

them. You really do have to show up everyday with ideas to keep things moving along. And sometimes that’s hard, because there are days when you don’t have any ideas. But it’s also difficult to find material that is commercial that doesn’t make you feel bad in the morning. These are great opportunities for me.

Q: Is finding commercial material conscious? Do you say, ‘It’s been a couple of years, I should find something commercial again?’

Soderbergh: It’s just balance. I want to move in any direction that I want. And part of that is once in a while you have to make a movie that somebody’s heard of.

Q: You were able to get everyone back for the last one. Will they all be back again this time?

Soderbergh: Yeah, I checked with them before we even got started to make sure. I said I had an idea but I wasn’t doing it unless everybody was on board.

Q: You also have a project about Che Guevera.

Soderbergh: We’re actually shooting six days in New York this month, which we’re then going to hold, and the rest of the film will be shot next year.

It’s hard to describe because we’re still working on the script. I have been on and off – I was on initially and then I left and then Terry Malick came on, and then I came back on. But it’s something that Laura Bickford, who produced Traffic, and Benecio and I have been talking about since Traffic, and we’re just now starting to get close to having the script the way I want. He’s a very complicated subject. He’s one of the few figures that holds up the more you scrutinize him, but he was really complicated. There’s a lot of story there, and we’re trying to figure out what story we’re going to tell.

Q: How will you make it different from Motorcycle Diaries?

Soderbergh: Our movie is about Cuba and Bolivia. This is a war movie.

Q: Are there any aspects of what Malick brought that might carry through in your version?

Soderbergh: When Terry was working on the movie it was only about Bolivia, so there might be some stuff from there that might survive. But the sequence that we’re shooting now is when he came to New York in December of ’64 and spoke at the UN. I guess the UN is going to be refurbishing and we have to get in there before we do.

Q: Can you talk about getting Robert Pollard of Guided by Voice to do the music, and why you decided to go with just an acoustic guitar for the soundtrack?

Soderbergh: It was a last minute desperation move basically. The good news about Robert Pollard is he’s very quick. I’ve always been a huge fan of Guided by Voices, so I had mentioned Guided by Voices in an interview years and years ago, and his management had put me on his mailing list. I started getting discs and things. Then I went to see one of their shows in New York last year–I hadn’t seen them live ever—and met a guy named James Greer there who had just wrote this book on Guided by Voices that was released in November. He asked me to do an introduction to the book, and I did, and I met Robert Pollard. He lives in Ohio, and it just seemed like the right thing to do.

Q: Could you explain why you chose to call this Bubble?

Soderbergh: No, it just kind of popped into my head. On the most superficial level, that’s how I would describe Martha and Kyle’s relationship, something really beautiful and really delicate, and then Rose showed up and popped it. Literally, during one of the nights when I was just working on the thing. I have a notebook for whatever project I’m working on, and I had just written that as a possible title.

Q: What about the decision of releasing it on DVD and in theatres at the same time – is there a reason why someone should see this in a theatre rather than just waiting a couple days for the DVD? Is it a different experience?

Soderbergh: Oh, sure. I just don’t know if you can judge whether one is better or worse. You can take the view that this is all an example of how people are disconnecting and they’re staying home, and they’re not having communal experiences. Maybe that’s true, but as long as it’s legal, I don’t know how you’re going to stop it, and I really don’t have a desire and I don’t think we should be trying to control how people experience art. They can see it on a screen or on a T-shirt. I think if you’ve got something that’s interesting, it doesn’t really matter how they’re seeing it. I’m not precious that way, let’s put it that way.

Q: You’re the kind of director who is always working and we’re always hearing about projects you’re doing. Why do you work so hard and why do you have so many projects going? Soderbergh: Yeah, it’s a problem, but why wouldn’t you? It’s the best job in the world. Why wouldn’t you be busy. I can’t image if you were in a position to have a lot of people say “yes” why you wouldn’t get a lot of people to say “yes”. I’m 42, and I feel like I still haven’t made my best work. I’m young enough to have the energy to be busy, and I’m experienced enough to be in a position if I pushed to make something that I think is really, really good. I feel like your ‘40s, you gotta get on it. I can see a time where I’ll just stop.

Soderbergh: Yeah, it’s a problem, but why wouldn’t you? It’s the best job in the world. Why wouldn’t you be busy. I can’t image if you were in a position to have a lot of people say “yes” why you wouldn’t get a lot of people to say “yes”. I’m 42, and I feel like I still haven’t made my best work. I’m young enough to have the energy to be busy, and I’m experienced enough to be in a position if I pushed to make something that I think is really, really good. I feel like your ‘40s, you gotta get on it. I can see a time where I’ll just stop.

Q: And what about your production company, Section 8? It’s done after this year?

Soderbergh: Yeah.

Q: Why?

Soderbergh: The work load was too heavy for me. I think we both felt [he and partner George Clooney] that it would be finite. We wanted to go out with Abbey Road and have it be something that never went bad. A little while back we decided – it was funny, when we made this decision to have the company end at the end of the next term, people were not liking what we were doing. It’s funny that now we’re on an upswing and I hope that will continue to the end of the company. But it had kind of run its course. We learned a lot, and we worked with a lot of terrific people, but I’m not a producer by trade, and it was having an effect on my ability to do my day job, and that was becoming a concern. And I think it was becoming a concern for George, too. As we can see he’s a director, and I think he’s interested now in pursuing that more than what the company started.

Q: Where do the ideas keep coming from?

Soderbergh: I asked Robert Pollard, who’s written thousands and thousands of songs, a remarkable number of them good, ‘Bob, where do the songs come from?’ He said, ‘The suitcase. I reach into the suitcase.’

Q: Your own career has been so well documented while you’re still working. How do you feel about having your career encapsulated already in a number of books, and having so many filmmakers cite you as an influence?

Soderbergh: You can never associate yourself with having the kind of influence the filmmakers you admire had one you. You just can’t. If you could, that would be a sign of a serious personality defect. I don’t have sense of that at all. It’s just that the lens is not going in that direction. My job is to make stuff.

Q: But when someone writes about you, do you read it? Did you read Waxman’s Rebels on the Backlot?

Soderbergh: I read some of it.

Q: How did you feel about it?

Soderbergh: There were a lot of errors, so I just stopped.

Q: Did you try to contact her and correct it?

Soderbergh: No. I’d rather have an idea.

Q: You’re premiering this film in Parkersburg, Ohio, where you shot it. Is this the kind of film that the people of Parkersburg would be interested in if they weren’t in it?

Soderbergh: I don’t know. I think tomorrow night’s going to be really interesting because I don’t know what they’re expecting, but I don’t know if it’s this. We were just talking about this, the question of are people like this underrepresented in movies because nobody wants to see them or because there haven’t been enough made to generate interest for people to see them. Is it a chicken and the egg question, or if more movies like this got made would people whose lives were like that say, ‘Oh, I really enjoyed that.’ Or do they go to the movies and say, ‘I don’t want to see that – I get that at home.’ I don’t know, I guess we’ll find out.