Every single person who visits this site fancies themselves a film fan. From the nameless readers who don’t interact to the regular Chewers on the Boards to every single person on the staff – we love film. We live for it. We watch as much of it as we can. But, sadly, we’ll never be able to see everything. We’ve missed a lot over the years and sometimes we’ll miss one of the big ones. One of the classics or cult favorites that has had everyone talking and proclaiming their love for years. That’s what this column is all about – catching up on those Big Ones. Maybe it’ll get you to rewatch an old favorite you haven’t seen in years, maybe it’ll get you to catch up on your own list of shamefully neglected films. If nothing else, it’ll at least give you an excuse to yell at us for waiting so damn long to see something. So dig it.

I caught Pulp Fiction randomly on some Blockbuster VHS way back when and fell in love. But it wasn‘t just the move, I fell in love with Quentin Tarantino as a director. That was the first time that had ever happened for me personally and while I went on to obsess over every single detail about the film (I’m almost positive that I stopped counting viewings somewhere in triple-digits), for the first time I became curious about what happened behind the camera. I say quite often that Pulp Fiction is the movie that made me want to watch more movies, but what I don’t say enough is that Quentin Tarantino is the first filmmaker that made me want to make them – basically, Tarantino was my Kevin Smith. I followed his career with tremendous interest from then on – I even stole the VHS of Four Rooms from my aunt’s video store because he was involved with it – but even though it’s been on my list for some time, I’d never gotten around to going back to the beginning and seeing where it all started. Until now.

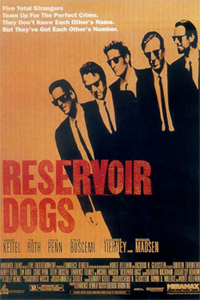

Reservoir Dogs (1992) – Buy it from CHUD

Reservoir Dogs (1992) – Buy it from CHUD

By now it’s probably pretty well understood that Quentin Tarantino is a film fan first and a filmmaker second. Maybe it’s not even so much a case of “one then the other” but a case of one informing the other, as in without the one there wouldn’t be the other. All that rambling aside, that seems to be the primary idea behind QT’s writing and directing debut – “movies are so fucking cool.” There’s an enthusiasm here that’s palpable. That’s not to say that there ISN’T the same enthusiasm in the rest of his output, but while later films like Basterds and Death Proof mix enthusiasm with actual master-class chops and confidence, Reservoir Dogs is built upon a raw, natural (but unrefined) talent that’s powered by sheer enthusiasm. “Movies are so fucking cool – and I’m making one!” You can almost hear him giggling behind the camera as that glee permeates every frame. It feels a lot like a student film in that respect.

The difference, of course, between Reservoir Dogs and any other random student film is that Tarantino came out of the gate knowing…well, maybe not TOTALLY knowing, but having a pretty damned good idea of who he was as an artist. On the surface, the story is extremely straight-forward – a group of criminals stages a heist, shit goes wrong, then shit goes REALLY wrong. It’s nothing we haven’t seen a hundred times in a hundred movies before – hell, certain elements from the movie are lifted directly from other films in a sort of hodge-podge of nods and references. And Tarantino doesn’t shy away from that story or change a single thing about it – there’s even an undercover cop! – but he tells it in a way that, while not necessarily revolutionary, was a change of pace from what mainstream American audiences were used to seeing. What he took was a standard time-tested formula for every run of the mill crime drama ever and ran it through the filters of what filmmakers like Godard and Kurosawa and Nicolas Roeg had been doing with the non-linear narrative and then injected THAT with the hyper-violence that came with big operatic crime dramas like Scarface and Goodfellas, but shrunk it down, made it small and personal and injected it with a dirty realism that mainstream American audiences weren‘t used to seeing. And then to top all of that off, our first glance at these gentlemen is at breakfast – they’re sitting around having a conversation, laughing and joking and living it up like life-long friends. It’s organized crime. That’s how these guys are – they’re family! It’s Goodfellas and The Godfather run through the French New Wave-cum-The Taking of Pelham 1-2-3 Cool Filter. But as it turns out – fuck that – they don’t even KNOW each other. He takes the one defining element of every crime drama and strips it away and it gives a completely new level of depth and humanity and meaning to the events that unfold. So, while you’re watching Reservoir Dogs there’s this weird sort of thing happening. You recognize nearly every ingredient there is, but you’ve never had them mixed this way before and it‘s refreshing. And that’s if you’re even familiar with the ingredients. If you’re NOT? Then you just had your life changed (I would know – again, the same thing happened with me and Pulp Fiction).

Now, none of this is to say that the film is perfect, because it isn’t. Great? Yes. Fuck yes. Flawless? Not at all. But again – it’s that enthusiasm that fills in the gaps and makes it work. You can tell Tarantino is trying to do something; he’s planted a seed about what cinema is and does (and can do) in his own mind and Reservoir Dogs is his trying to cultivate it and share it at the same time. There are a few stumbles along the way – one scene where Keitel’s Mr. White double-fists several rounds into the chests of a couple of policemen feels like it would be more at home in a Troy Duffy movie, for instance – but what’s probably the biggest misstep is in Tim Roth’s Mr. Orange. Unless I’ve glossed over something, Mr. Orange is the first, last and only time a policeman plays a central character in a Tarantino film and it really didn’t work. Mr. Orange’s story (arc?) seems like the only element of the film that didn’t have a Tarantino twist on it. His piece of the puzzle is completely paint-by-numbers and even though Roth gives a great performance and it’s HIS blood on the floor that sets up the uneasiness that Mr. Blonde’s Big Moment pushes over the top, it sticks out as the only “normal” piece in a film full of exceptional, which, in context of the whole, is a bit of a failure. And you get the sense that Tarantino felt the same way, as when Pulp Fiction came out – which, in essence and hindsight, really feels like a remake of Reservoir Dogs to fix the shit QT didn’t like – that type of character was excised and replaced by someone new – a woman.

That’s another area in which Reservoir Dogs sticks out from the rest of QT’s output – there’s no female character in the film period (unless you count the unseen waitress from the pre-title and the poor woman that Mr. Orange shoots as “characters”), let alone a central female character who’s responsible for driving at least a large part of the narrative, if not the entire thing. I don’t know if it’s entirely accurate to say that Mia Wallace actually replaced Mr. Orange, but what ends up becoming the most interesting aspect (to me anyway) in finally seeing Reservoir Dogs after seeing everydamnthingelse, is that Mr. Orange was the last time we spent any real time with law enforcement in ANY Tarantino film. Maybe it’s safer to say that Mr. Orange was replaced by Earl McGraw who, one could argue, is as much of a bastard (if not more) than all of Tarantino’s characters and, in any case, is always relegated to the sidelines – showing up after all the bad shit happens (or just in time to BE the bad shit in the case of From Dusk til Dawn, which, in case you weren’t aware, was directed by Robert Rodriguez but written by Tarantino).

At first I wanted to consider what that said about Tarantino’s views on law enforcement in general (though certain snippets of dialogue in Reservoir Dogs may betray a little of that), but what dawns on me is that Mr. Orange goes against what seems to be Tarantino’s views on humanity in general. Mr. Orange is a quintessential good guy, but even more so than that, he’s the quintessential archetype of The Good Guy Who’s Pushed to Do Bad Things and he’s the only Tarantino character who fits that mold. Every other character in every other QT movie (including the rest of the gang in Reservoir Dogs) are either Bad Guys Who Are Bad (Mr. Blonde, Joe, Eddie), Bad Guys Who Have So Much Humanity That You Like Them Anyway (Mr. White) or Good Guys Who Do Bad Shit Because It’s Human Nature (we didn‘t get this until Bruce Willis‘ Butch in Pulp Fiction – Mia Wallace may count as well) – nobody else matters (for an example of that last part, look at Mary Elizabeth Winstead‘s Lee in Death Proof). Beatrix Kiddo was The Good Guy but she was capable of some repugnant shit. The Basterds were the same. Zoe, Kim and Abernathy were a bit different in that they were just plain good and killing wasn’t part of their outwardly shown nature, but they didn’t blink an eye when time came to fuck shit up. Violence is as much a character in a Tarantino film as Vincent Vega or Aldo Raine and it’s because Tarantino sees it as an inherent component of human nature that he’s more comfortable working with characters who embrace that aspect of themselves. Mr. Orange did not and he died more than one death in that movie.

But, even though Mr. Orange died his deaths in not only Reservoir Dogs but in Tarantino’s outlook for the future, almost everything else about this movie gives us a full-on stare (as opposed to a glimpse) at what Quentin Tarantino planned to unleash upon the world. The signature shots, the narrative beats, the thematic elements, the sizzling dialogue, the amazing use of music – Tarantino came out of the gate swinging with all of that. And he did it while pushing the envelopes and stepping over the boundaries that were reserved for only the greatest, most respected artists of that time. Yeah, Reservoir Dogs isn’t any more violent or profane than Scarface or Goodfellas, but Quentin Tarantino wasn’t Martin Scorsese or Brian DePalma. He was a nobody with a stupid name who worked at a video store (you’re doing it wrong, Randal) and he made a movie that, while flawed and fuzzy in an auteristic sense, said “Fuck your conventions – I’m gonna show you how this shit is done and I’m gonna have a fucking blast while I’m doing it.”

The amazing thing is, nearly 20 years later, he’s still saying the EXACT SAME THING.