Doctor Who: A Fairytale Life #1 (IDW, $3.99)![IDW Doctor Who[5]](http://www.chud.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/IDW-Doctor-Who5.jpg)

By Adam Prosser

It’s not a very original sentiment, but it’s true: Doctor Who is probably the closest TV has ever come to capturing the insane, intricate, wildly imaginative and immensely nerdy style of a long-running comic book. It’s a SF character originally intended for children, whose mythology grew denser over the years as more and more people began obsessing over it and former fans became writers. It’s changed creative staff so often that the question of the show’s “author” is mostly irrelevant. It’s got an “anything can happen” premise, it’s rebooted itself in-continuity, it’s constantly reflecting the era in which it was made. And then there are the spinoffs.

Doctor Who comics have been around for ages in Britain—Grant Morrison wrote them back in the day—but the show’s only just starting to make a real impact in North America, and (original) Doctor Who comics have only been around for a couple of years. The publisher, natch, is IDW, who’s lately surpassed Dark Horse as the king of multimedia licences (and is doing a decent job of it, from what I’ve seen.) With the show gearing up to REALLY break through across the pond (or across the Pond) with this weekend’s big shot-in-America premiere, the timing is right for the first comic appearance of the 11th Doctor and companion Amy Pond. (This issue appears to be set early in the first Matt Smith series, before Amy’s fiancé Rory joined the TARDIS crew.)

Amy, like a surprisingly large number of the Doctor’s companions, seems to be getting bored with the wonders of the universe remarkably quickly, so when the Doctor asks for a challenge, she asks him to take her into a world of fairytales. The Doctor obliges with a visit to a far-future, planet-wide renfaire which seems to have forgotten that it’s a tourist trap and mistaken its technology for magic. Also, the planet was quarantined a while back. Oops.

Writer Matthew Sturges crafts a story worthy of the show, with the trademark snappy patter from a Doctor who’s usually too fascinated by his surroundings to worry about imminent danger, and the “fairytale” theme is a logical (if slightly obvious) extension of the current show’s parallel of Amy’s adventures with her childhood imagination. The multi-person art team has that snappy, cartoony art style that I enjoy, and they capture Amy’s likeness dead on (their version of Matt Smith’s Doctor seems a little off-model, but it’s close enough).

All in all, Doctor Who comics seem kind of inevitable—it was always a question of *when* we would get them here in the Colonies, not if. If IDW hadn’t pulled it off, someone else would have. Fortunately, IDW has a solid claim to the material with this book, and the Doctor’s gradual multimedia and pan-global domination can continue unabated. Who said the British Empire is dead?

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Danny Husk in: The Hollow Planet OGN (IDW/Desperado, $19.99)

Danny Husk in: The Hollow Planet OGN (IDW/Desperado, $19.99)

by Graig Kent

I came to The Hollow Planet as a fan of comedian/actor/writer/podcaster/gay icon/jack-of-all-trades Scott Thompson’s work across all the various media he’s partaken in, from his pioneering web community Scottland in the late 1990’s to his current Scott Free podcast. I was (and remain) an avid fan of Kids In The Hall — the ’90’s sketch comedy show that’s sandwiched firmly between Monty Python and Mr. Show as the best of all time — and I have followed Thompson’s post-KITH career more closely than any of the other troupe members, perhaps because I find him to be the most approachable personality of the group (having met him a handful of times would seem to confirm that). It was through his podcast that I heard about Hollow Planet, and to be honest, I wasn’t sure what to expect. Thompson’s humour often aims (and succeeds) at being bawdy and provocative (infamously having waved a dildo around on stage at a poetry awards dinner where he scandalized Margaret Atwood, for but one example), and while it’s rarely for simple cheap laughs, it’s not always to my taste.

This book was sold to me basically as a BDSM-comedy-fantasy, which left me quite wary – as comedy-fantasy (nevermind the BDSM part) rarely plays well (see Your Highness for a recent example) – and ultimately quite unprepared for what the book is actually like. Utilizing his oft-used everyman Danny Husk as the story’s focus, the opening sequence introduces Husk as he’s out with his wife and children at a mountain-side carnival. Despite the suggestive first image that opens up the book the opening sequence is played fairly straight, heavy even, when Husk’s son disappears, nowhere to be found, and no witnesses to his disappearance. A few year’s later, Husk’s family life is strained, he’s paunchy and graying but still striving to keep his spirits up. We’re given an exceptionally and effectively well orchestrated glimpse into Husk’s daily life, only now peering in as hidden things in the background of his life start to escalate into the fore. Synchronicity. As everything builds to a head, Husk falls into a chasm, only to awake in a more primitive world where he’s enslaved, frequently beaten and molested, all to his surprise and pleasure. Time passes, Husk grows accustomed to and welcoming of his new life, but also discovers that in spite of his seemingly inconsequential status, he actually has a greater role to play in this odd kingdom filled with giants, trolls, elves, wooly mammoths and more. It’s a skewering of the typical heroes journey but played out in a much more low-key fashion.

The bondage-slavery element of the book is surprisingly (for Thompson) underplayed, verging on respectable even. There’s an astute contrast between the world and life Danny Husk leaves behind and the new world he’s both enslaved in and escaped to. Thompson’s lenghty-but-perfect investment in introducing Husk and his life pays plenty of dividends for the character throughout the book, as he grows, changes, and yet remains very much recognizable as the same man from the beginning. (Kids in the Hall fans may have a little difficulty in reconciling the previous iterations of Danny Husk with this one, but Thompson develops the character here in a depth he never has before). One of the biggest adjustments in expectations though is in understanding that character and story are Thompson’s priorities here, and comedy doesn’t really have a focus. The book isn’t a comedy, in the sense that there’s no shenanigans, no pratfalls, very little innuendo (the sexual element is refreshingly forthright and not necessarily played for laughs), and any actual humor comes organically out of the characters and their situation.

It should be noted that The Hollow Planet is a graphic adaptation of an unsold screenplay of Thompson’s, adapted by Stephan Nilson, but unlike, say, Kevin Smith’s Green Hornet, Thompson was intimately involved in the adaptation and production of this book, working with artist Kyle Morton to ensure his longstanding vision of this passion project is achieved. Nilson and Morton do an excellent job making the book feel like a comic rather than a film, the format of an original graphic novel giving them plenty of room to breathe and extend sequences visually as necessitated by the story. Morton’s art is at first unassuming, cartoonish but not unnaturally so, yet as the story progresses, his skill and technique start to incrementally impress. His characters are exceptionally well designed, and the simplicity of his figures and settings are deceptive in their effectiveness and attractiveness. Ron Riley’s thoughtful colours fill in the space Morton leaves beautifully, establishing different tones and hues depending on time of day and lighting source. I was leery of the art based on the cover, but frankly the cover is the only unattractive thing about the book.

If there’s a weakness it’s a big one in a surprisingly truncated ending. Given how airy the rest of the story is, that the big confrontation and fight sequence begins and ends in under eight pages is awkward, ill fitting, and disappointing, and the two-page sequence that follows, closing out the book provides little closure. It feels less like a stopping point and more like a dozen pages are missing. Thompson has stated that this is the first of a planned trilogy, and it’s unfortunate that this book doesn’t end on such a note that it screams for more, nor does it truly imply where further adventures might be headed. Yet it is definitely well executed and enjoyable enough, with characters genuinely worth caring about, to deserve a follow-up or two.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Suicide Girls #1 (IDW Publishing, $3.99)

By Devon Sanders

You really never know what to expect from a book about naked folks. So, when you get an actually entertaining story, you should respond with the appropriate shock and amazement and tell people about it. So… Thor’s Comic Column readers, Suicide Girls #1 is an actually entertaining story with a great little back story, solid dialogue and stellar artwork.

In a very possible future, conformity’s become absolute. Those who choose not to are locked away and broken by the WAY*OF*LIFE Organization. A single woman by the name of Frank sits behind prison walls, trying to find a way out. A wall crumbles and a way out, found. The Suicide Girls, an organization spoken of as only myth, have come calling. They could use a woman like her to help shake up the world.

Writers Brea Grant and Steve Niles have taken an idea that could easily been held up as dubious and made it interesting through the use of dystopain future and the idea of The Suicide Girls as a trust as old as America itself. As a die hard fan of 100 Bullets, I’m a sucker for this stuff and with a blend of some damned good characterization and whipsmart pacing, they made me a believer. Penciller David Hahn (Bite Club) and Cameron Stewart (Batman And Robin) come together to provide some of the most gorgeous art I’ve seen in years. From the cover on, every line of art displays economy and an absolute understanding of the story’s needs. There are plenty of women being drawn here but not one panel of it can be interpreted as overly gratuitous. Kudos to them for this, their character design and major love to Stewart for channeling his inner Kevin Nowlan and making it all look so damned polished.

Suicide Girls #1 is a comic that simply exceeded my preconceptions and frankly, I very much believe that was the point of this book, after all.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Dark Horse Presents #1 (Dark Horse, $7.99)

Dark Horse Presents #1 (Dark Horse, $7.99)

By Adam Prosser

It’s hard to tell a story in just a couple of pages. Some people can’t even manage to make a comic self-contained within a full issue. Anthologies are particularly tough, though, since the temptation is to simply start up a larger story and slap down a “to be continued”. But that may be a feature, not a bug, for Dark Horse Presents, one of the more venerable comics institutions making its triumphant return to the stands this week with a raft of heavy hitters in tow.

This showcase of some of Dark Horse’s upcoming material features a new Concrete story by Paul Chadwick (one of the few truly self-contained stories) as well as previews of new series by some old-school heavy hitters: Neal Adams gives us the bizarre “Blood”, which starts out as a crime drama before taking a loopy turn into SF (or does it? The narrator relating the story may be unreliable); Howard Chaykin begins the crime story “Marked Man” which, unfortunately, just comes to a stop before he can really give us the hook; Frank Miller previews some black and white pages of “Xerxes”, the 300 sequel (the art is up to a standard that Miller hasn’t achieved in a while, though his reliance on constant splash pages seems a bit lazy); and Richard Corben offers the truly odd but stunningly drawn fantasy “Murky World”. All of these are just barely getting started when they end, making them seem more like a vague taste than even a first-course meal. But the taste is pretty sweet in the case of Chadwick and Corben, and Miller and Chaykin’s work looks like it might be interesting as well. (Adams’ work is growing increasingly disjointed and erratic, as readers of Batman: Odyssey know all too well, though “Blood” at least makes narrative sense. It’s possible that this series will have its wacked-out pleasures, but it’s probably the weakest entry in this anthology.)

Excitingly, this comic also features work from two terrific creators who may finally get their due. After almost two decades of obscurity, Carla Speed McNeil’s awesome “Finder” has been picked up by Dark Horse and gets a showcase here. “Finder” is a really hard series to describe, taking place in a post-apocalyptic cyberpunk world that’s nevertheless frequently indistinguishable from our own, providing a nifty satire of modern life. The stories range from sweeping epics to surreal fantasies to tiny slice-of-life stories (like the one showcased here) and spans generations, following an immortal “Finder” who can, well, find anything for anybody. McNeil bills it as “anthropological SF” and if the series is about to break through thanks to Dark Horse, a lot of people are in for a treat. Meanwhile, David Chelsea—best known so far as the writer/artist of an amazing graphic how-to guide (Perspective! For Comic Book Artists) launches an amusingly whimsical series called “Snow Angel”, about a little girl who can apparently turn into a crime-fighting angel by falling backwards and flapping her arms in the snow, as we’ve all done. Chelsea’s art is technically superb but has an alluringly abstract, enigmatic feel to it—he always reminds me a bit of Windsor McCay, artist of “Little Nemo”—and I look forward to this series, which seems kid-oriented.

The book is rounded out with a prose piece by Harlan Ellison (one of the few pieces that doesn’t seem to be promoting any future work), a prologue to a new Star Wars series, and a pair of comedies: a Mr. Monster story by Michael T. Gilbert (I’d heard of but never read Gilbert’s Mr. Monster before now—turns out it’s a pure comedy that has the feel of classic MAD Magazine) and a couple of truly funny one-page gags by Patrick Alexander, the one guy in this book I’d never heard of. But then, that’s what a book like this ought to be for: promoting new talent.

While I feel that this book errs slightly on the side of “promotional material” rather than a comic that has value to the reader in and of itself, the high quality of the work within nevertheless makes it stronger than the average anthology. If nothing else, it’s worth it for Chadwick, McNeil and Chelsea, and to celebrate the return of an institution to the comics stands.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

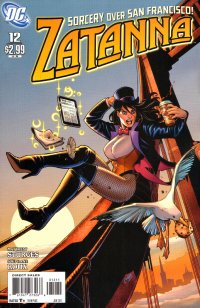

Zatanna #12 (DC, $2.99)

By Jeb D.

With all respect to the efforts of Paul Dini and his ilk, as a character, Zatanna remains a mildly awkward reminder of a simpler day in superhero comics, when a sexy costume and cheesy power were enough to get you into the Justice League. So while she seems ill-fitted to the darker tone that often gets imposed on her adventures these days (though heaven knows, she’s better off than the poor Spirit), every now and again, someone comes up with an idea for a story that embraces the politically-incorrect goofiness of the simpler time in which she was conceived, and reminds you why the old-school “one and done” superhero story, with outrageous villains and B-movie perils, still has its adherents.

The only problem with reviewing this issue is that the storyline hinges on a concept that I really hate to spoil. I’ll say this: writer Matthew Sturges has given some thought to the way that Zatanna’s powers work, has considered them with the solemnity of the young comics reader we all once were, and devised an elegant challenge for her in the form of a bad guy with a unique method of holding off her vocally-based magic (no, it’s not sticking a ballgag in her mouth; I did say “elegant”). And, naturally, our heroine (with a bit of magical assistance) finds an equally elegant riposte.

You can tell that Sturges came at this story with that concept in mind, since the early section takes pains to show us Zatanna practicing her backwards-speech (is it a retcon that she has to actually learn each new word inversion?). He also continues comics’ recent love affair with our City By The Bay, as Zatanna rhapsodizes about San Francisco’s magic, its famous landmarks, the breeze in her hair, and at one point pretty much flies right over my office. Artist Stephane Roux is clearly also enticed by San Francisco’s photo-op settings, and the book is lovely to look at (though he’s another one that tends to make Zatanna’s chest look like an enormous, bulbous white water bottle hanging around her neck).

Interrupting Zatanna’s idyllic travelogue is an adversary that also has the random weirdness of a Silver Age villain: a short-tempered would-be rapper from England named Backslash who appears to be bad more or less just for the hell of it, who carries an imprisoned fairy around with him, and whose dialogue was cribbed from Guy Ritchie movies. We do get a nod to modern sensibilities when he starts things off by casually murdering some innocent mer-folk, but otherwise he’s classic old-school, not least in that he just happens to possess a specific power that just happens to be specific trouble for the particular superheroine that he encounters. Zatanna even gets a vintage “knocked-out-from-behind-and-awaken-tied-up” scene, as Backslash does his gloating in rap form. But, as I say, with a little fairy assistance, Zatanna trumps his power (ten bucks says that the idea for this entire story came when Sturges was pondering one specific line of dialogue), puts things to rights, and she and the now-freed fairy even get a farewell posed in front of the Golden Gate Bridge.

I don’t want to oversell the virtues of this book, particularly since I’m not one of those insisting on a return to the “one and done” concept (what’s the point of an ongoing integrated universe if you don’t take advantage of its full scope?), but it’s always nice to see a writer who can bring some of that old “Hey, kids-comics!” feel to a modern superhero story.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars