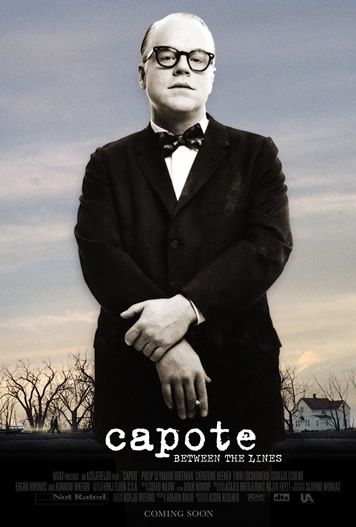

I haven’t seen all the movies that will be vying for awards attention at the end of the year, but I have seen a bunch. And it’s hard for me to imagine that any of the ones coming up will contain a performance as immersive and impressive as Philip Seymour Hoffman’s in Capote. He takes on the famed author and raconteur’s voice and mannerisms completely, cloaking himself totally in Truman.

I haven’t seen all the movies that will be vying for awards attention at the end of the year, but I have seen a bunch. And it’s hard for me to imagine that any of the ones coming up will contain a performance as immersive and impressive as Philip Seymour Hoffman’s in Capote. He takes on the famed author and raconteur’s voice and mannerisms completely, cloaking himself totally in Truman.

The film tells the Behind The Novel story of the writing of In Cold Blood, a seminal moment in modern literature. It’s a non-fiction novel, and it really changed the way people write in a huge manner. It’s also just really fucking good, and it tells the story of the horrible massacre of the Clutter family in a small Kansas town by petty crooks Perry Smith and Dick Hancock. Capote, along with childhood friend Harper Lee (he’s the character of Dill in her classic novel To Kill a Mockingbird), came to Kansas right after the killings and became completely entwined with the life – and death sentence – of murdering Perry Smith.

I had a chance to talk to Hoffman at the Toronto Film Festival. He began this round table terribly guarded, even holding his hand over his mouth. Over time, though, he became really engaged. Although there were a couple of journalists at the table who he seemed to just really, really dislike (and before you think it was me – it wasn’t! This was still a week before Dreyfuss would punch me, so my karmic negative interaction with a celeb was still coming).

Q: You take Truman Capote’s voice and mannerisms head on, but how did you keep what you were doing a performance and not just an imitation?

Hoffman: Just concentrating on the story. Probing into that story and understanding everything about it and everything about why he did what he did to get what he wanted and why that was such an obsession and all those things – as long as that was the core of it, what was making him tick… I knew that if that wasn’t happening all the technical work I was doing would be fruitless.

Q: That said, was it important to have that voice?

Hoffman: Of course it is. It would be impossible – I couldn’t just go up there and say, [still in his normal voice] ‘OK, I’m Truman Capote.’ People would have been walking out in droves. Part of the story is that he is the guy that he is in Kansas in 1959. That’s part of the drama.

Q: What’s the daily preparation for that? Do you spend the day as Truman?

Hoffman: You spend the day when you’re working not as Truman, but as the actor technically sticking close to the voice and the physicality because dropping it – it’s more exhausting. You got to stay in it. But when you’re finished, you have to let it go and take a rest.

Q: Do you like Truman Capote? And is it important that you do like him, as a performer?

Hoffman: Ultimately you have to love who you’re playing. I think you have to have that kind of feeling. You have to have passion for the person. I was in a constant state of trying to understand why he did what he did and justifying it and defending it and trying to get behind him.

Q: But does that mean you have to condone what he does? He lies to Perry – their relationship is built on lies.

Hoffman: It’s not built on lies. The relationship is not built on lies. He had to lie to Perry to be able to do what he needed to do, but the relationship I don’t think is built on lies. Otherwise the tragedy wouldn’t have unfolded – he would have coldly allowed them to die, it wouldn’t have been a big deal. He would have been, ‘I’m a journalist and I wanted to write this piece and these guys did this thing and they died.’ That’s missing the point a little bit. In my opinion the relationship itself was built on an extraordinarily powerful bond and identification that ultimately had to be betrayed because of what he had to do.

Q: Well, it had to be betrayed but there is that aspect towards the end where Truman’s back in New York and he can’t wait for the Supreme Court to just sentence these guys to death already. So on that level, can you condone that aspect of him being an asshole?

Hoffman: You shouldn’t condone it when watching the film.

Q: But you as the actor.

Q: But you as the actor.

Hoffman: Me as the actor? OK, you see him in the premiere scene at the bar. That’s not a guy who’s like, ‘Oh fuck man, when are these guys going to die?’ It’s not. It’s a guy who’s like, ‘I need them to do this, it’s torturing me.’ He’s tortured because he knows that’s what it’s going to take, and he needs that to happen. That’s when you start to see the self-destructive part of him. That disease, the selling of the soul – you start to see the price he’s going to pay. That slowly creeping self-reflection starts to creep in and he starts to see himself in the bright light that’s unbearable. He starts to project that all over the place. I think all those things were happening at once.

I think there are moments where he was known to say, ‘God I hope they die,’ and to be cold about certain things, but I always remember Joe Fox saying after the execution that [Truman] cried from the minute they got on the plane to the minute they got off. So that’s Kansas to New York. That’s a good three and a half hour flight where he sobbed the whole time. And Joe Fox isn’t some embellishing guy like Truman – Joe Fox is a guy who is telling you this happened. Gripped his hand the whole ride home. So you know that wasn’t for the cameras, that wasn’t for this, that was him going, ‘Ohhhhhh fuck.’

Q: And he never finished another book.

Hoffman: He wrote four chapters of Answered Prayers, never finished that. And look what little he did with that did – it did a number on him too. [The first chapter was published in a magazine. Many of the characters in the novel were obviously based on Truman’s society friends, who were horrified at how he treated them. He lost many friends as a result.] But he never wrote another book. He never wrote another novel. He never finished his great work, which was going to be Answered Prayers, his Proustian effort, which he had been talking about for years. He was finished.

Q: Was it a direct result of this?

Hoffman: It’s never just any one thing, but he said ‘If I had known what it would have taken, I would have driven through Kansas like a bat out of hell.’ But yeah, our take was that this had to do with what happened after.

Q: There are two sides of Truman – the public side of Truman that people know from his appearances, but also a private side that we see here. How did you come to that side of him?

Hoffman: I had to make a lot of assumptions, I had to make choices based on what I found out and read and whatever. There’s a documentary that the Maysles made called With Love From Truman that covers him in black and white right around the first printing of In Cold Blood, so around 66 or 67. You get an impression of him privately in that. Even though he’s being interviewed and is on camera, they capture him in a lot of different settings, and being the talents that they are, you do get a sense of him in a private way.

But the majority of what I had to do was that guy who was not as well known.

Q: Do you think that you would have liked Truman in real life?

Hoffman: I think that I would, actually. Obviously it depends – there were a lot of people who liked him very much and then he did them wrong, and they stopped liking him. So who knows, I might have been on the bad end of the stick with him at one point. But ultimately if I was just a passive observer, or met him or hung out with him a little bit, I think yeah, I would have. Just because who else is like that guy.

Q: Do you think that Truman would have been as big a success if he hadn’t been such a self-promoter?

Hoffman: I don’t know if this answers it, but I think he was always concerned with how he was being perceived. I think that’s what creates a good PR person. I think he was very concerned with how he was being received, and to be accepted and to be admired and to be loved – everybody is concerned with that, but it was a huge character flaw in him. I think it was endless in him.

was being perceived. I think that’s what creates a good PR person. I think he was very concerned with how he was being received, and to be accepted and to be admired and to be loved – everybody is concerned with that, but it was a huge character flaw in him. I think it was endless in him.

Q: So was he as much an actor as a writer?

Hoffman: He wasn’t an actor. You know, everybody’s an actor if you want to say that. You’re an actor. Everybody’s changing who they are in an environment to deal with – I don’t think that’s unique to him at all. That’s a human quality.

Q: Why did it take so long for a Truman movie to happen?

Hoffman: Because he’s such a mimicked, iconic, out there character in our society. I think it’s a dangerous place to go. There are a lot of pitfalls in there. It took somebody attacking it from an angle that was going to be as artistically fruitful as possible.

Q: Can you talk about the relationship between Truman and Perry? Was there an attraction?

Hoffman:

The problem is that you want to compartmentalize your life. You want to

be able to say, ‘Oh that has nothing to do with that. And if I do this,

I can live with it.’ That was the problem. He couldn’t separate his

obsession and attraction and need for Perry Smith with the project. It

was inseparable, and fed into the ultimate demise. He couldn’t have one

without the other. He couldn’t say, ‘I love you. I am obsessed and

fascinated. I want the best for you. Could you be executed? Is that

possible?’ That sounds so silly, but you know that ultimately that was

the dilemma. It was a no-win situation.

Ultimately at the end of the

day he was going to be abandoned once again. He was going to be left

once again. I know that sounds as self-centered as possible, but the

grief he’s feeling there at the end is the self-reflection that’s

crushing. He can’t be left alone again. It sounds weird, but it’s this

unbearable, inconsolable grief mixed with this self-reflection of him

as an asshole.

Q: You seem to be juggling mainstream films, like Mission: Impossible 3 with smaller films like this. How do you choose these roles?

Hoffman: I try not to plan that too much. I try to get a vibe and a feel for what it is and it usually answers itself. But there are certain things I don’t want to do so much anymore, so some things are easy choices. But ultimately what I will do next is always up in the air for me. As much as I want to say, this is what I should do, or now I’ll do a blockbuster – I don’t really function that way.

Q: Do you always have to get something personal out of it?

Hoffman: Oh yeah, personal’s huge. Even Mission: Impossible 3, there has to be something personal that I want to get out of doing it. Even if it is about career, still there’s got to be some draw of it being a personal ambition of mine to want to do it. On top of the identification with that character and getting the story told. There’s a certain aspect to the character I’m playing Mission: Impossible 3 that’s new to me, and that’s something I wanted to explore.

Q: Can you tell us about the character?

Q: Can you tell us about the character?

Hoffman: He’s a bad guy.

Q: Where does theater fit into this mix? You have a theatrical company, LAByrinth, which is a large part of your creative life. When you do a play does that put your film work on hold for an indefinite amount of time?

Hoffman: You have to plan your life accordingly to do what you need to do or want to do. I don’t think, ‘God I’m not going to be able to do a film for a while if I do this play.’ I’m doing the play because I want to do the play.

An actor said to me years ago, ‘Why do you take yourself off the market like that?’ I was like, ‘What?’ I had no idea what he was talking about. Take myself off the what? This is what we do.

Q: There’s something else going on right now that I want your take on – the influx of film actors taking stage roles. We have Julia Roberts, who has never done theater, making her debut on Broadway in Three Days of Rain.

Hoffman: What a wonderful play. That’s smart.

Q: Lots of stage actors could probably play that role wonderfully –

Hoffman: And she might be one of them. And that’s a beautiful play, and she’s pretty smart to pick that one to do. Now that I know that, that’s impressive. That’s not like, ‘I’m going to put myself in Into the Woods.’ She is going to do one of the great contemporary dramas. It’s really beautiful and that’s a great part.

Sometimes we’ve been quite surprised. I think of Christian Slater, who’s doing all this theater now. I have all the respect in the world. I’ve met him a couple of times – that’s his life. It’s who he is. He’s an actor. Sometimes actors change up. I directed Anna Paquin in her first play. She’s done like seven plays since then. She’s a known, legitimate New York theater actress. But when I hired her…

Sometimes I think you’re right. Sometimes screen actors come in, do their duty and they leave and never come back. But some of them don’t and we’ve got to hold that out if it’s possible.

Q: There’s been buzz about the possibility of awards. Is that something you think about?

Hoffman: Oh, it’s so much more interesting talking about all this stuff! No, to be very honest, because I’m a very hands on producer on this – it’s not just a name, Cooperstown is my company – if that does happen, I’m very excited. I think I would be more nervous if it were just about me as an actor, but it’s legitimately much more than that on this project. It allows me this kind of room to go, ‘Wow, that would be exciting. What if a ton of people saw this movie that we put together and it’s our first film!’ That’s exciting – who wouldn’t be excited about that? Awards season can always help a film that way.

Q: You’ve known Bennett Miller, the director for a while, but this is his first film. What gave you the confidence to go with him?

Hoffman: I’ve known him since I was 16. It’s been a long time, 22 years. I read Danny Futterman’s screenplay and I was like, ‘He’s good.’ So that was over. And Bennett – Bennett’s been a filmmaker since he was a teenager. I’m a person who would know that. Nobody else would, but I know that. He’s a very successful commercial director. The one film he made, that documentary film he made, was a huge critical success. He just hasn’t had much failure in the venues he’s tried as a director in the film world. I just know how bright he is and how smart he is. I know he’s not going to say, ‘I’m going to do something’ unless he knows it’s the thing to do. So here we were, we were 35 or 36 at the time, and now he’s saying he wants to direct a feature? That must be the one! So it was easy for me to champion him as the director through the trying to get money part.

Q: Having followed you for a number of years now, you’re the kind of actor who not only takes lots of interesting roles, but you often play really raw and open and emotional roles. But are there places you won’t go?

Hoffman: There are certain parts – and I can’t get specific, I just know it when I read it – there are certain parts where it’s like, ‘Eh, I don’t want to deal with that.’ You have to trust that. It’s kind of like when you go see a movie sometimes, you go, ‘I know this is good, but I don’t want to deal with it.’ It’s too much. Sometimes you like those movies, sometimes you don’t. It’s personal, it’s right there in the moment.

It usually has something to do with things I’ve already done. Things that have to do with things I was more interested when I was younger. I don’t want to go there again. And sometimes it’s just blatant – I want to call up the person who made the offer and go, ‘I have done this. Move on!’