BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE!

BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE!

STUDIO: Miramax Home Entertainment

MSRP: $29.99

RATED: R

RUNNING TIME: 76 Minutes

SPECIAL FEATURES:

• Commentary w/ director Jennie Livingston, editor Jonathan Oppenheimer, Willie Ninja, and Freddie Pendavis

• Outtake reel

One of

the things I like about documentary filmmaking is that it allows a group or

individual to express themselves to an objective, non-judgmental eye. Some

people may be willing to open to a camera when they wouldn’t to a human being;

others may have dreamt about being in such a position, and so the camera captures

a unique side of them, the showy side. Subtleties of character ride high during

these interviews because it’s possible for the interviewees to forget that,

while the camera doesn’t care how they act or what they say, their performances

will be seen by an audience who does.

Paris is Burning is concerned with a subculture

built on performance, the gay cross-dressers of New York City in the late 80s,

who resolve their differences with "vogues" or dance-offs (long

before Madonna got her flashing hands on it). Each of the filmmakers’ subjects

is flamboyant in performance and subtle in implication, which makes for a

compelling and well-rounded documentary.

The lost chapter of Kill Bill.

The Flick

Director

Jennie Livingston splits her documentary into two distinct sections; the first

was filmed in 1987 and is the meat of the film, the introduction to the

subjects, their world, their slang, their hopes. The second takes place in 1989

and acts more as a denoument, revisiting those individuals from the first

section that could be tracked down, or were still alive.

Just

about everyone who sits down to this film will be in the dark as to its

material, so Livingston spends a good portion of the running time letting her

subjects explain the intricacies and the importance of the fashion balls that

dominate their lives. The balls are opportunities for gay men to flaunt their

dress-making skills, or their ability to pass as a woman, or their fashion

sense. More than once you’ll hear someone compare the fashion balls to

title comes from.

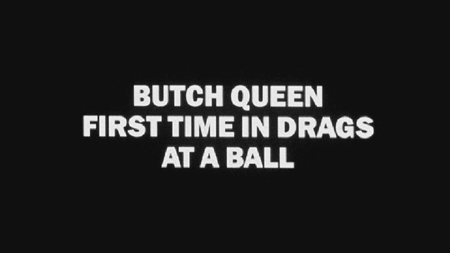

These

fashion balls have been going on for some time, according to Pepper LaBeija,

one of the "house mothers" (essentially gang leaders for harmless

men). By 1987, any given ball might have thirty or forty categories in which

the attendees might compete, ranging from "A Day in the Country" to "Butchest

Girl". The winners in each category are presented with trophies, and beam

as though they had just been awarded the Miss America crown and plastic

flowers.

She likes her furs fresh off the vine.

Another

word you’ll hear bandied about right alongside "

than one of

be legendary in the fashion or dance worlds. In the presence of so much

compressed hope, the fashion balls take on a special significance. Not only are

they a proxy for turf wars between the different gay houses, but they are also

a chance to be — within the confines of the gay, cross-dressing,

There’s a

backlash of emotion from those of

audience, realize that this is a pretty low branch to leap for. A common meme

among the disaffected is that only white men can achieve what they want in

life, and only white women can live in the lap of luxury. The social context

has shifted since Paris is Burning was filmed, but the mindset persists and is

relevant to the audience. These sequences, intercut with shots of business-men

and -women going about their days is broad daylight, carry an undisguised

victim complex, and it’s up to the viewer to determine whether that’s deserved

or not.

Some of

the subjects have set themselves up to be victims. Venus Xtravaganza, for

example, is a petite, pale, soft-wpoken young man who, in the 1987 section,

gets picked up on the street often by men who, she claims, don’t want sex 99%

of the time. 95% of the time, she amends after thinking for a moment. She

hasn’t been able to get her sex change operation. She talks extensively about

how great her life will be when she can find a man she loves, can move up into

the mountains or down to

mother, Anji Xtravaganza, worries to the camera about how Venus goes around

with anybody who shows the slightest interest in her, chasing after her dream

in every direction but the right one. In the 1989 section. Anji explains how

Venus was found murdered after her body lay for four days in some dive motel.

A shirt, a skirt, a pair of gloves, and a bath tub plug.

There’s

no condemnation of Venus’ choices by the filmmakers, but she is contrasted

heavily against Willie Ninja, the mother of the House of Ninja, who wants to

take voguing worldwide. In 1987, he declares to the camera his conviction that

the vogue, with its origins as gang warfare between the gay houses, will become

a sensation from one side of the globe to the other. In 1989, the filmmakers

revisit him and we hear about his trip to Japan, how they loved voguing over

there, and about the choreography work he has picked up since declaring his

intentions two years previous.

Between

these two memorable, contrasting stories,

gay man who has been around much longer than any of the young cusses we’ve seen

so far. Dorian is quiet and seems modestly educated in her vocabulary. She can

remember back in her prime when the men used to try and look like Marlene

Dietrich. Her interview is filmed from a small number of angles in her dressing

room as she applies makeup, preparing for exactly what we’re never quite sure. Her

sequence is intercut throughout the film, and her casually wise observations

form the backbone around which the other subjects cling, though they may not

know it. Dorian possesses a nonchalance that borders on fatalism regarding her

lifestyle: it’s what she does, it’s what the others do, and they can’t help it.

Some of them succeed, some of them fail. Dorian gets the last line in the film,

and it’s so perfect one can’t help but feel it was rehearsed.

That’s

kind of the point. These gay men are constantly performing — in life, as they

try to act like what society prefers; in the balls, as they show off for

judges; for themselves, as they try to achieve their own ideals. With

statistics leveled against them, it’s easy to see where Dorian’s enthusiasm

went, but with success stories like Willie Ninja’s to counterbalance, the film ends

on a pleasantly unresolved chord.

7.7 out of 10

Legs, legs everywhere, nor any drop to drink.

The Look

The film

stock used originally wasn’t of the highest quality. There is a large amount of

grain during shots with low lighting, and a certain monochrome tone to a number

of the interiors. What was present on the original print is preserved nicely,

here. I have no complaints about the transfer.

The

visual style is kept engaging throughout the film, with a nice mix of static

and moving shots. The settings chosen for the primary interviews are all

interesting, visually: Pepper LaBeija’s dim dressing room and crowded living

room, Octavia Saint Laurent’s wall of models, Anji Xtravaganza’s relatively

opulent sitting room, and Dorian Corey’s backstage mirror.

7 out of 10

The Noise

Dolby

Digital mono. The dialogue during interview sequences is well-captured, but

that of impromptu meetings on street corners or during balls is muffled and

require the use of subtitles. The soundtrack is kept fairly clean, with only

occasional musical interjection.

All in

all it’s serviceable, but hardly noteworthy.

5 out of 10

"This, this here, is my friend, old woman."

The Goodies

Paris is Burning has one of the most fascinating

commentary tracks I’ve had the chance to hear. Not only do we get the director,

Jennie Livingston, and the editor, Jonathan Oppenheimer, but we get two of the

subjects of the film to lend their observations: Willie Ninja, mother of the

House of Ninja, and Freddie Pendavis of the House of Pendavis. Alongside the

technical and cinematic observations offered by the former two, we get some

stream-of-consciousness memories from the latter. Ninja and Pendavis, though

their maintained flamboyancy, add unexpected notes of pathos to scenes of

humor, and lighten the serious moments with their affected gravity. It’s a

great track, for the contrasts of character as much as anything else.

Other

than that, the disc has only an outtake reel that doesn’t offer much. It’s a

bare-bones presentation, but if they had to include one good bonus feature, the

commentary was a good one.

7 out of 10

The Artwork

The cover

looks like a bargain bin eighties movie, the sort of thing you might

accidentally mistake for Fatal Attraction. The cast

photograph in poorly-composed and unbalanced, and surrounded by a cheesy

Photoshop glow filter. It’s exactly the sort of thing that admirers of the film

will warn potential viewers to ignore, and to just dive into what it hides.

3 out of 10

Overall: 7 out of 10