BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE!

BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE!

STUDIO: Walk Disney Home Entertainment

MSRP: $29.99

RATED: PG

RUNNING TIME: 119 minutes

SPECIAL FEATURES:

• Trailers

• TV spots

• Animated storyboards

Studio

Ghibli has a history of putting pro-environmental messages into their films,

covertly and overtly. Such a message was the entire plot of the fanciful Nausicaa

of the Valley of the Wind, and the fight between technology and nature

was more than metaphor in Princess Mononoke. Neither of those

occur in the real world, but even Spirited Away (which, arguably,

does) drew in a bit of that tension on one of its many sub-threads. Pom

Poko does similar to the latter, in casting real-world humans as the

villains in the struggle, but, like Nausicaa, makes the fight to

maintain nature the center of its narrative.

That’s a

lot of

Takahata, the man who also gave us the film that most geeks are proud to admit

made them cry: Grave of the Fireflies. Initially, Pom Poko might strike a

viewer as immature, childish (not child-like), a bit of woodland propaganda. Watership

Down with less prophecy. I encourage those viewers to stick with the

nearly two-hour film; amongst the playfulness, there is a realism that dogs the

events, and brings the conclusion to a somber, thoughtful resolution.

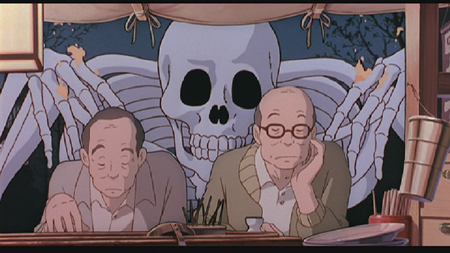

Three seconds had to be cut from this scene to make the PG rating.

The Flick

It is the

year thirty-one in the Pom Poko calendar. (Why does that

matter? Because the story spans a couple of years, which puts the ending right

around year thirty-three.) In the Tama hills near

are finding that their forest is shrinking. They put aside their squabbles for

food and territory to investigate the cause, and discover that the humans are

encroaching on their land, building brand-new housing developments to satisfy

the demand in

The

raccoons refuse to let their beloved land be destroyed, turned to muddy banks

and asphalt, so they resolve to do something about it. That something, as it

turns out, is to reclaim their magical powers of transformation, train the

young ones in how to infiltrate human society, and torment the construction

workers whose hands are causing the symptoms the raccoons fear. Up until this

point, the narrative feels realistic (except for the talking raccoons, and the

contextual animation styles, which I’ll talk about later), but here Takahata

starts to steer us in the direction that he’s aiming. Pom Poko becomes a modern

myth, an extension of the animistic Japanese folk tales about clever foxes and

lazy raccoons. This becomes a surprisingly effective way of communicating the

story, deftly bridging the past and present.

Oh, Charlie X, you lovable cad.

The

animation style serves to support the myth-based narrative, though it’s not

obvious how until the above plot point. Rather than drawing the raccoon

characters as though they are real, as though the artists are merely glancing

through a window into another world and faithfully recreating what they see,

there are different animation styles applied to the characters depending on the

context. There are broad, minimal strokes for the raccoons when they are at the

extremes of their emotion, either happy or sad; there are slightly more

detailed, but still Care Bear-esque raccoons when they are acting out their plots

against humanity; and there are detailed, four-legged, realistic raccoons when

they are acting as raccoons in our world do. It’s not a new direction in

Japanese art, as it gets used extensively in plenty of modern manga and anime

(and to the point of brain-death in FLCL), but it is employed with

direction, here, and supports the narrative well.

Another

factor that contributes to the mythic quality of the film is the way the

narrative is expressed. It’s not given over to the characters to drive the plot

forward, but instead an omniscient narrator (voiced by Maurice LaMarche, Brain

on "Pinky and the Brain") who maintains a presence through the entire

running time. The individual characters are reduced to ciphers, and it is given

to the narrator to set up each vignette as it relates to the whole. Usually,

this is a no-no in film, but here it only works to reinforce the texture

Takahata was going for. Pom Poko ends up feeling like a bedtime

story, a fairy tale. You don’t get attached to the characters in fairy tales;

you remember the situations. You don’t know

Cinderella; you remember that the klutz tripped on a carpet and hobbled home.

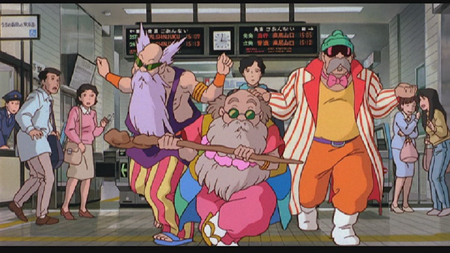

Masters of Transformation, yes. Masters of Social Interaction, no.

The

second act of the film is devoted to the raccoons’ attempts to frighten the

humans away, and it’s right around here the film earns its PG rating. (There’s

also the issue of magical raccoon nutsacks to address, but, well, I’d rather

not.) The raccoons kill humans. They terrify them with visions of melting

faces. They stage an elaborate parade through the burgeoning development that

is simultaneously more memorable and more disturbing than the "Pink

Elephants" sequence in Dumbo. Young children exposed to

this stuff would have glorious, amusing nightmares.

As the

story progresses, it becomes more and more complex. The raccoons who are able

to transform themselves into the likenesses of humans find that they enjoy

human society quite a bit, especially the food. They don’t want to push back

the humans completely, just out of their neck of the woods. A faction of

raccoons emerges who wants to destroy as many humans as possible, staging

guerilla attacks without the consent of the great raccoon council. Gradually,

the raccoons lose control of their focus and they fight a climactic, small, and

representative battle with the humans, setting up the bittersweet denouement.

Except

for a grating piece of direct proselytizing, the ending is handled with a lot

of subtlety. The raccoons, as a race, learn a lesson or two, and the whole

thing seems almost to come out in favor of humans, encouraging large housing

developments whenever possible. The tone of the ending contradicts that surface

reading, however, and adds a note of complexity to both side of the argument.

expansion are more clean-cut — pollution equals bad, nature equals good — but

Takahata brings out a bit of the anticlosure that made Grave of the Fireflies

such a success, and works it around, to a lesser degree, here.

The

running-time is a bit excessive for a story so simple — and it is a simple

story, despite the branching paths the characters follow while trying to

achieve the same goal. Myths don’t need to be overly complex, just memorable

and thought-provoking. Despite (or maybe because of) the disturbing imagery,

this is the sort of thing I would like to show my children. Gotta make the

little buggers think.

7.5 out of 10

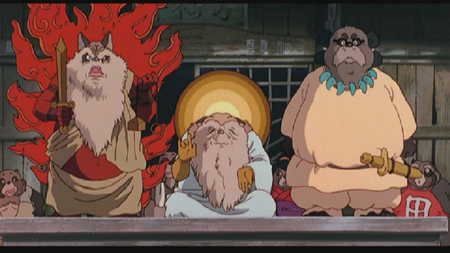

Hades, Buddha, and… Gus?

The Look

Widescreen,

1.85:1. I have absolutely no complaints with the way this film looks on DVD. These

Disney releases of Ghibli films have been top-notch all the way across the

board. The animation is typically beautiful, the three distinct character

styles all presented in perfect context. The landscapes have that vibrant,

familiar unreality that is typical of Ghibli films. The colors came across

perfectly, and the transfer is flawless.

9 out of 10

"Say, could I have a sake and a mop?"

The Noise

Dolby 2.0

Surround. The original Japanese language track is a joy, and the subtitles that

accompany it preserve more of the linguistic playfulness than does the English

dub. The dub is top-notch, though, with fewer of the hammered-in awkward

phrasings that interfered with Spirited Away.

The music

is beautiful, but hidden too low in the mix to be memorable unless you’re

digging for it. It would have fared much better in 5.1, I’m sure. Still,

there’s a good variety of instrumentation used to punctuate the major plot

points, and the tone is folksy where appropriate and fully orchestral on the

big dramatic cues.

7 out of 10

Authorial intrusion: I’m sorry, I– just– raccoon nutsack.

The Goodies

There’s

an extra disc of bonus features, but it’s kind of deceptively labeled, because

in actuality it is a disc of bonus feature.

The second disc consists entirely of a non-interactive set of original

storyboards. They’re interesting, sure, but they really ought to have provided

a menu to select which sequence you’d like to see storyboarded, rather than

presenting them in a lump.

The other

disc has trailers and TV spots. All together, it’s kind of disappointing for a

two disc set.

5 out of 10

101st Flying Nutsacks, away!

The Artwork

Taking a

glance at the front cover will give you an idea of how many different

characters the narrator has to keep tabs on. It’s positively Homeric. It also

gives a potential viewer the chance to see if they’ll be able to stand the

unabashedly cute mode of animation.

I’m not a

big fan of the stripes of color segmenting off the cover into title, picture,

blurb sections. It makes the thing look like a textbook.

5 out of 10

Overall: 7 out of 10