Insomnia & Hot and Bothered: Carnivale, S1, eps. 9 & 10

Samson: “You better hurry up and get born.”

Hola, devotees of Terminal Television! After a three week break in which I spent approximately zero hours doing anything close to approximating “fun” I’m back in the saddle again and ready to resume our journey through the dark heart of Daniel Knauf’s Carnivale. You may think this is hyperbole or half-assed excuse. NAY, I tell you! Verily and foresooth, I was off slaying a barely-metaphorical dragon and now I have returned, bearing scars but wiser for the battle. Sort of.

So let’s talk turkey and delve into the next two episodes. This column is a little shorter than usual. Given what I’ve just gone through it was a lot easier to talk about these episodes together than to take them separately, but my admiration for both of them should be stated up front. We’re approaching the end of season one and I have to say that these two installments almost make me kind of angry at the way the episodes that’ve come before have been handled. As I’ve said before and as I’ll indubitably say again I have no real problem with the molasses-esque pacing of Carnivale thus far but I’d be lying if I said that I found the show to be compelling, edge-of-your-seat television. It is not. Or at least it wasn’t, until the one-two punch of Insomnia and Hot and Bothered.

Maybe it’s a coincidence that Insomnia, the first of these two episodes, was directed by Jack Bender, who helmed so many memorable and hard-hitting episodes of Lost, but both of these installments possess something that every other episode hasn’t, really, so far: actual, honest-to-God moments of plot advancement, both large and small. This sudden willingness to actually address, however obliquely, the larger mythology/narrative of the show, is like a fresh, cool, welcome breeze after weeks spent trudging through the figurative desert.

The actors on this show are all capable performers, all a pleasure to watch, but I’m not tuning in to Carnivale to watch a period-accurate portrayal of Depression-era America, at least not first and foremost. I’m tuning in to see some supernatural shenanigans; some clashing-o’-good-n’-evil. This doesn’t mean that Carnivale needs to totally shift focus away from life in the carnival, but it does mean that the show needs to give us a reason to CARE about life in the carnival as it relates to the larger story being told. The characters, in and of themselves, don’t really do that for me unfortunately. With Lost I could have watched a show about that group of characters just hanging out on the beach together. The mysteries of the Island, while a driving reason for my near-crippling obsession with the show, weren’t the emotional fuel for my love of the show, if that makes sense. I cared about Jack Shephard’s daddy issues as daddy issues, not as possible extensions of a larger thematic point about our relationship with God. By contrast, I care very little about Ben Hawkins’ daddy issues except as they relate to the Apocalyptic storyline that hovers on the horizon, like storm clouds threatening to divulge their rain.

Insomnia and Hot and Bothered remedies this gripe. All of that fine character work we’ve been watching? Suddenly it’s spiced by a real and growing sense that Very Important, Ominous Things Are Happening and, more importantly, Carnivale’s characters are acting on that growing sense. Why do these moments of (usually character-based) spice make me kinda angry? Because it seems to me that they could easily have been sprinkled in more judiciously over the course of the season so far. They weren’t, and those earlier episodes suffer as a result. No longer are we seemingly disconnected from the larger unfolding saga, instead following the marital troubles of Stumpy and Ma Cooch. Now we’re watching a power struggle between Lodz and Samson for the attentions of the ever-mysterious Management as we also flit back to check on Ma and Pa Cooch and, again more importantly, we’re watching as those characters start to reach out to other characters in order to fortify their respective positions. This kind of scheming functions to illuminate character AND advance the plot, and their combination is twice as effective as what’s come before.

Your opinion may differ, and that’s hunky-dory by me. We all respond to art differently, and one person’s bane is another’s bliss.

So what actually happens in Insomnia and Hot and Bothered? Quite a bit, and most of it serves to advance the show’s central conceit – a threatened clash between Light and Dark. Questions get (sort of) answered, and there’s a growing sense that something’s coming to a head here. Both installments successfully fuse character-deepening work with supernatural mystery and manage to provide some sense of clarity to the proceedings in the process. As good as Babylon and Pick a Number are, I’d say that these two episodes stand as my favorites thus far for precisely that reason: they juggle solid character work and mythology with equal aplomb, and while we don’t learn a ton of new information the various pieces in play are all shuffled forward to some degree, and that advancement makes me hungry for more.

Let’s take Sophie’s mysterious parentage as our first example. We’ve known that her mother is Apollonia, that Sophie doesn’t know who her father is, and that Apollonia’s catatonia (hey, that rhymes!) apparently manifested upon Sophie’s birth. Sophie’s vision in Insomnia fills in many of the blanks in her story to the careful watcher, and what it reveals is as disquieting as it is interesting. Apollonia was raped, and her rapist is, we can probably assume, Sophie’s father. According to Sophie’s vision, her mother’s attacker was the unnamed fellow with the giant creepy tree tattoo, a figure we’ve only glimpsed in earlier visions but an especially careful viewing reveals that the image of the mysterious tattoo-dude is replaced briefly by an image of none other than….Brother Justin Crowe.

Which means, barring some kind of uber-surreal, uber-symbolic trickery, that Brother Justin is Sophie’s father. Via rape. Which, y’know, YIKES. It also means that Brother Justin and the tattoo-dude are either the same person or (maybe more likely) that Brother Justin is to Tattoo-dude as Ben Hawkins is to Henry Scudder – the inheritors of an Avatar legacy. The actual meaning is really kind of unimportant right now. What is important: the show is connecting these characters together in meaningful, mysterious ways that make me, a member of its intended audience, want to watch more Carnivale.

Notice also that Apollonia’s eyes turn black as pitch at the end of her brutal encounter with tattoo-dude/Brother Justin – the same inky black that Justin himself his displayed in Ben’s visions. As awful as it is to type these words I have to wonder if that’s not the moment when Sophie is conceived, and that thought makes me wonder a great deal about who or what Sophie actually is. After all if the whole Avatar thing is really passed from generation to generation as the show seems to be suggesting, and if Justin is actually Sophie’s babydaddy, as the show ALSO seems to be suggesting, then Sophie is probably an Avatar, yes? That would explain her ability to read her mother’s thoughts, no? This impression is further cemented in Hot and Bothered, as Sophie is approached by a member of the Knights Templar at the All Saint’s Day carnival she attends. The man utters the same words that were spoken to Justin and Ben in their second-episode vision, adjusted for gender: “Every prophet in her house,” indicating that Sophie is like and/or connected to Ben and Justin. Something potentially interesting to note: All Saints Day is a celebration dedicated to people – Saints – who have experienced “a beatific vision” of God after dying. What’s a beatific vision of God? It’s an unfettered, direct view of God. And what have Ben and Justin been doing so far on this show? Experiencing visions which are perhaps a means to experiencing just such a beatific vision while they are still alive.

The tattooed-dude pops up again in Hot and Bothered during one of Ben’s momentary lapses of consciousness, standing in the middle of an open field, then again in the middle of Hawkins’ road like a fate Ben can’t escape. He rears his ugly mug yet AGAIN in the building that houses the Templar order, featured in a ridiculously prominent painting. It’s absurd that neither Ben nor Samson happens to notice the GIANT PAINTING OF THE CREEPY TATTOOED GUY prominently displayed IN FRONT OF THEIR FACES. But its still a great image in a show filled with great images.

Lodz: “They will teach you to face your own power and control it”

Also percolating in Carnivale’s coffee pot this week: Lodz’ as-yet-veiled plans for Ben Hawkins. We learn in Insomnia that Hawkins is fighting off sleep in an effort to stave off the dreams/visions he receives when unconscious. This does not look like fun. Given the unavailability of Red Bull and Five Hour Energy back in the day it seems even less fun. Lodz says something interesting during all this not-sleeping: without the dreams Ben “can’t be reached.” So who is trying to reach him? God? Satan? Management? Lodz? For what purpose? To teach him about his heritage (that seems the most obvious choice)? To warn him about Justin? To draw Justin and Ben into confrontation?

Lodz’ act of “reading” objects also comes into play during Insomnia in a major way. Lodz experiences the Templar visions when given Scudder’s Templar charm. Ben somehow knows the meaning of the latin phrase on the Templar charm and chants it twice, seemingly uncontrollably. I find it particularly fascinating that both Ben and Justin are drawn to the imagery/symbolism of the cross, and the way in which the cross is invoked as a sign by which they may conquer. It raises interesting questions about the symbolism of religion in general and about the ways in which religious symbols are used to justify atrocity.

Samson: “Something happened in the old country. Something real bad. Badder than anyone can imagine.”

But that ain’t all that’s happening in the confines of the Carnivale. As mentioned, Samson and Lodz are engaged in a struggle for Management’s attention, and Lodz appears to be winning that struggle. Interestingly, Samson seems genuinely unaware of the specifics here. He knows Hawkins is important to Management, but not why. Lodz seems far more educated on all things Metaphysical and Mysterious. And so it makes perfect dramatic sense that Samson would angle to align himself more closely with Hawkins. It develops these characters even further AND advances the show’s overarching mythology all at once. During Hot and Bothered, Samson takes Ben to one of the Templar order’s locations – and I’m reminded again of that as-yet-unexplained phrase from the beginning of the season, and which rears its head again in this very episode: “Every prophet in his house.” Is the Templar order a kind of “house”? And what further connection does the mysterious Phineas Boffo have to Ben Hawkins?

Even as these questions are rearing their questioning heads we’re starting to get answers as well. Scudder’s time with the carnival preceded Management’s presence – in fact, Management apparently bought the carnival after Scudder departed from it, and has been using the carnival to search for Scudder ever since that time. The vision Ben experiences at the end of Hot and Bothered shows us that Scudder is claiming Ben as “his,” which, given his snarling, mad-eyed look, suggests that Scudder may not have been an Avatar of Light at all. Is it possible that Ben is a part of the Avataric line that represents the forces of Darkness? That Justin is actually the representative of the Light? If so then perhaps the notion of free will – which I have been downplaying in a major way, focused on the seeming fatalism that suffuses the show – is present in Carnivale after all. I’m very interested to see if more light is shed on this.

Iris: “You have a destiny. And now is your time to fulfill it.”

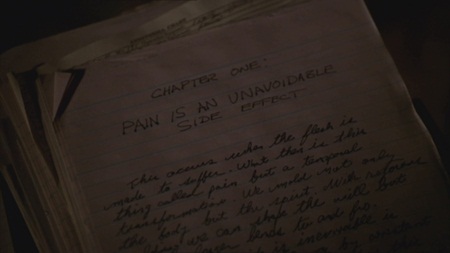

And speaking of Brother Justin, Hot and Bothered gives us a reunion between Justin and his sister – an icky, uncomfortable, veering-dangerously-toward-incest reunion – and we learn that Iris has always known about Justin’s abilities, has intentionally been “protecting him” from them for what’s likely decades. Brother Justin’s story snaps into full, ominous focus during these episodes as he continues to develop his wonky powers. The eerie ease with which Justin expands and extends his abilities stands in stark contrast to Ben Hawkins’ continual refusal to exercise his abilities. Justin’s influence appears absolute – he can essentially control others’ minds at this point – and this point is nicely driven home by the reappearance of the disbelieving doctor who interviewed him in the last episode. The doctor is a disheveled mess, and he’s all too eager to help Justin. Justin had previously asked for paper and something to write with, but was denied those items. He’d remarked that they weren’t necessary, and these episodes show us why. As Justin leaves the hospital, Doctor Disheveled hands Justin his psychiatric file, which also contains what appears to be a religious manifesto authored by Brother Justin titled “Acts of Redemption by Brother Justin Crowe.” The first page of this manifesto is visible to us, and we can see that its initial topic is pain as transformative agent.

Tommy Dolan finally meets Brother Justin again during Hot and Bothered, and interestingly Justin doesn’t seem interested in taking advantage of Dolan’s newfangled Radio Pulpit. I’d have thought he’d be on that opportunity like white on rice/like Justin on Iris but that’s not the case, at least not thus far. Justin seems far more comfortable with the act of reaching out to others in their physical presence as he does at the end of Hot and Bothered. He enters the church of his mentor/father figure (Norman, who’s a welcome presence here and assumedly a growing presence from this point on) and proceeds to diagnose the congregation’s sins like some kind of spiritual physician. He demands a new baptism from Norman, and the water that Justin’s mentor uses turns to blood on Crowe’s forehead, ominous to be sure, and a wordless repetition of the Templar motto we’ve seen before: “In this sign you will conquer.” Justin ends these episodes in a place of power – he has the confident purposeful demeanor of an Old Testament prophet. It feels as though we’re reaching a tipping point in the narrative – the time of initial discovery and confusion feels as though its coming to a close, and more secrets and revelations loom just around the corner. I hope I’m right about that, and I hope that the last two episodes of Season One are as good and as intriguing as these.

It’s good to be back. Thanks, as always, for reading and for commenting. I’m sure I’ve missed things worth discussing, and I know that there are vast portions of this episode that I didn’t deign to touch upon. Frankly, Jonesy and Sophie’s weird halting romance and Ben’s attraction to a woman old enough to be his grandmother just don’t provide much fuel for my writing fire. I invite you to bring up stuff you’d like to discuss below, or on the message boards. What did you think of these episodes? And what do you think of Carnivale, now that we’re this close to the end of its first season?

All screencaps courtesy of fishstick theatre.