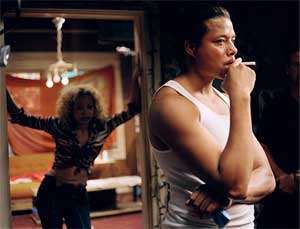

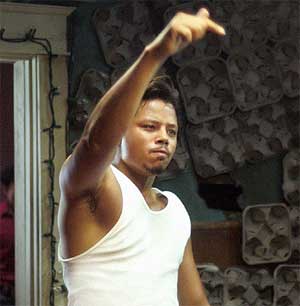

There are five more months in the year 2005, but I doubt I will see many movies better than Hustle & Flow. Hustle & Flow is a fantastic film, featuring a classic performance by Terence Howard, an actor who has been doing supporting roles for too long.

There are five more months in the year 2005, but I doubt I will see many movies better than Hustle & Flow. Hustle & Flow is a fantastic film, featuring a classic performance by Terence Howard, an actor who has been doing supporting roles for too long.

It’s written and directed by Craig Brewer, who is essentially a newbie – he has a previous film shot on DV, but no one has seen it. Hustle is a gritty, sweaty joy of a film, and he’s created an indelible character in the hustler turned rapper DJay, a character that Howard brings to glorious life. Of course Brewer needed someone to believe in him and get the film made, and that someone was John Singleton. Singleton, who should go back to making films more like Hustle & Flow and less like 2 Fast 2 Furious, made this whole thing possible.

At the press day for the film both men came in together, ebony and ivory. Brewer, you see, is a white dude, which might surprise a lot of people. What won’t surprise anyone who has seen the film, though, is the fact that Brewer’s a smart guy, with a lot to say – especially about his home town of Memphis.

Q: What do you say when people ask if we need another pimp and ho flick?

Singleton: Another one? When’s the last time you saw one?

Brewer: That’s something that we’ve been talking about among ourselves, because that seems to be the dead horse everyone keeps beating. Why are we seeing another one of these? Do we need to see another pimp with a dream doing rap? But I don’t think I’ve seen this before. I’ve seen movies where pimps are parodied and there’s some pageantry to it, but I haven’t really seen anything – I can’t think of anything recently. I’m not saying that I’m right – I’m just offering up to people what this is. When I was rollin’ around in Memphis, I saw these characters and what I felt is that I hadn’t seen this character before. Usually what I see is the guy with the Kangols and the silks and the ice but I haven’t seen a guy who is like the guys I showed you [to Singleton] on Summer Ave. walking behind their girls five steps, sitting in a Chevy Caprice sweating their ass off with their one girl. Going from shake joint to shake joint. I know some of these guys, and I never referred to them necessarily as pimps. It’s one of the things they did; I thought of them more as hustlers. They would sell me anything. That was a story I was really interested in.

I got to meet those people because I was making my own indie film on DV, and if you’re going to make a movie for no money – I’m not even talking about the movie that John helped me make – I’m talking about the movie I made before John came along. When you’re making a movie for no money and making it on DV, you really do have to hustle and do it on a street level. The shake joint you all saw in Hustle – the guy who owns that died two days ago. He was this old country guy he would open up his shop on Sundays, and let me come in and film, and he’d ask his girls to come in and be my extras, and that was because I said, ‘I’d like to invite you to the premieres’, and I said I’d put his lead girl in a scene. I’m constantly having to do more of a street hustle to make art. So that’s why that, and that’s why now. There’s been a lot of posturing like, yeah I could be a rap star, I could be this, but no one’s ever shown the process of it, and no one’s ever shown how that kind of street hustle parlays into a persons mojo.

Singleton: I think this film transcends DJ being a pimp or even a hustler. He’s a guy who basically has not got to where he wants to be in life. One thing we all talked about making this movie, is the intriguing thing about this guy is that he does things, as a character, that the audience doesn’t like, but he’s a likable guy. He’s like Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull or Stanley Kowalski in Streetcar. He’s that kinda guy. We had Terence watching Marlon Brando in Streetcar-

Singleton: I think this film transcends DJ being a pimp or even a hustler. He’s a guy who basically has not got to where he wants to be in life. One thing we all talked about making this movie, is the intriguing thing about this guy is that he does things, as a character, that the audience doesn’t like, but he’s a likable guy. He’s like Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull or Stanley Kowalski in Streetcar. He’s that kinda guy. We had Terence watching Marlon Brando in Streetcar-

Brewer: And Tony in Saturday Night Fever

Singleton: -and characters that had an edge to them. He’s this guy that you like, but you don’t like the things he does. That what flips people out and that’s what kept it from being made for so long. Because all they saw was ‘pimp’ and they said we don’t wanna make this. But the interesting thing is, this is not the stereotyped glorification of a pimp advertising with the suits and the gators. This guy is a chauffeur. He’s a broke guy who’s on his last leg; he’s on his last leg even while he’s holding these girls together to get them to do what he wants them to do.

Q: John, how did you get hooked into being a producer on this?

Singleton: I met [Craig], and Stephanie, who helped me get my movie Boyz n the Hood made, got me the script. I loved the script and I saw Craig’s first movie, and I thought this guy deserves to be making movies, so I got on.

Q: Craig, if the pimp thing is the dead horse, the elephant in the room is that you’re a white guy writing and directing this movie. Should we move beyond that, or is there something that needs to be said about that?

Brewer: No, I understand the curiosity and the question, and I don’t take an attitude with that at all. For a long time in Hollywood when I was banging on the doors out there, there was a lot of curiosity and caution. And I’ll be the first to say that there needs to be more caution, because I learned a lot about the system when I tried to make Hustle. One thing that’s interesting about that system is that no one would have a problem with me making Hustle if I just made it goofier, if I made it funnier. Or if I made it with a little bit more action. And I was told in no uncertain terms by a lot of studios, that in terms of movies with predominantly African American casts, that there are already set ways that Hollywood can make money off of them. They didn’t want to deviate too much from that. They didn’t want to make a movie where you identified with this guy. They wanted to see a movie where we could laugh at him, and we could laugh at the girls. And I’m not saying that there are not moments where we do that in Hustle, but I don’t think that’s what the core of the movie is about. And also, I don’t think…even though there’s episodes of violence, it’s not something where I’m shooting sixty frames per second and DJay’s flying through with two shiny nines blazing.

But that’s what they said it was OK for me to do. If I were to tell a personal story, they were worried that this would not be a star vehicle where a major star would want to do it, so the only way they could publicize the movie would be to say this is a personal story, which it is. But I’m not allowed to do that through this, and it’s even more scary, and this is where I completely understand their position and their point. Part of the iconography of the cinema that we’re exploring with the 70s hustler character who’s on his last leg; that’s like falling out of a stereotype tree and hitting every branch on the way down. He’s a black pimp, he’s  got a white hooker, and he’s trying to make rap music. It doesn’t change the fact that I know black pimps, and they’ve all got white hookers, and they’re trying to make rap music. I was telling them I don’t want to do an urban movie. I don’t want to do a black film. They’d say, ‘Craig look at the content.’ I’d say I want to make a Memphis movie. And I was going to make this movie for five grand on DV after I made my first movie and so I was going to make a Memphis movie. And I really feel that Hustle is a Memphis movie. I’m glad that America gets to see it, but I was perfectly content with only Memphis seeing it.

got a white hooker, and he’s trying to make rap music. It doesn’t change the fact that I know black pimps, and they’ve all got white hookers, and they’re trying to make rap music. I was telling them I don’t want to do an urban movie. I don’t want to do a black film. They’d say, ‘Craig look at the content.’ I’d say I want to make a Memphis movie. And I was going to make this movie for five grand on DV after I made my first movie and so I was going to make a Memphis movie. And I really feel that Hustle is a Memphis movie. I’m glad that America gets to see it, but I was perfectly content with only Memphis seeing it.

Singleton: We had people at the studio turn it down because Craig is white. And that was bullshit. Guys know me — I am about people having social responsibility and making black themed projects, but very few people have really done it and done it well. People point out Norman Jewison as one of them because he takes the heart of the story for what it is, and tells it for what it is. This is a situation where Craig is Southern, and Southern in a way where he’s influenced by blues and rock and crunk, and when you look at the picture, it’s his vision. I got involved with this because I respect his vision.

Q: John, you not only signed on as a producer, but stepped up with money to greenlight the film. What was it about Craig’s early film that sold you?

Singleton:I felt that this goes beyond artistic merit – I felt this movie could make money. He was telling a story that was worthwhile. He had a good idea of the cast he wanted in the picture, and I’m tired of the bullshit of the industry saying that only a certain type of film can get made. And I was tired of going through the same channels to get a movie made. So this is part and parcel of something I’ve always wanted to do, which is to find a way to make movies outside of the system. With the success of Hustle, I think that if I have a movie that’s within a certain budget range, I’ll never go to a studio again. Ill just go ahead and make it. I don’t want to negotiate to get the money to do it.

Brewer: Now that I’m getting involved with a studio, I’m now understanding exactly what that means. If any of you liked Terence Howard, and thought that he was really amazing in this movie like I thought he was, that’s because John was my studio. Every single studio that I took it to said ‘absolutely not’. And even worse: ‘He’d be perfect. Absolutely not.’ And that’s because of box office cache, whatever, but when John’s your studio, he can gauge what’s going to be your special effect in the box office. If you don’t have a lot of money and time to shoot a movie, your special effect is the performance. That’s what I learned on my first movie, having no money: it’s not so much what you’re shooting with, as what you’re shooting at. If you’re going to have a movie that’s gonna be this bold, then we would need someone like Terence. That’s when John would say, of course you need someone like that. Or also, even more so: we’re going to have Anthony Anderson, and he’s not going to be funny in this. You know? Do you know how many notes I would get on this? ‘We need clips with Anthony.’ And these are realities. These are things that really have been said to me. And because John was the studio, the movie had a more truthful center.

Singleton: I just got to a point where, in my career, I’d made a film that just made 230 million dollars worldwide, just did 5 million copies on DVD, which is another 200 something million. I was like, fuck it. I want to find a way to make movies out of the system. I went around with this script with Craig and they shook our hands and said, no we don’t want to do it. I thought it was a no-brainer with the team of me Craig and Stephanie. I thought we could get it made. And now the beautiful thing is, I know that I can get a film made at a certain price out of the system. I’ve talked to a lot of independent film makers and a lot of talented people. I can call up Halle Berry or Chris Rock and say hey, you guys want to do a movie? Let’s go do a movie right now. That’s empowerment, and that’s what I want to do.

Q: Craig, you’ve talked about making a shorter version of Hustle on DV – can talk about how you wrote the film — how long it took and what the process was?

Brewer: This one came out of me really quick, because I really was making a story about the experience I just went though making the first movie. Because my father had died rather unexpectedly. He was a healthy guy, and he just died of a heart attack. I’d written a script called The Poor and Hungry and he really loved it. It was about car thievs in Memphis. I was trying to shoot on film, and I didn’t have any money, and me and my wife were really struggling for a long time just to make ends meet, much less make something like am movie. He told me I should just shoot it on DV, and not apologize for having few tools, but almost celebrate it.

So I started making that movie and after my dad died I got about 20 grand of inheritance, and I lived off that for about a year and a half, and bought equipment. I bought an editing system, and video cameras from Circuit City — Digital 8 — I think some of you probably have better cameras than I was shooting my movie with. But this movie kind of rescued my wife and me. We were building sets in our house. We were trying to quiet down neighbors, we were kind of filled with the sense that, if I’m 24 and my dad died at 49, then I’m almost over. Throughout that whole process it was a very stressful time, and I just thought that was a more interesting story. The process, and ultimately a person who feels that he does have one shot,  and he has to get going now.

and he has to get going now.

And it really came out of me in a couple of weeks, because I had this experience with this one pimp. I had known pimps and hustlers and girls before, but this was this kind of gorgeous iconic look. He rolled up in this pieced together Chevy Caprice on dubs. He was a black pimp, and he had this white girl with microbraids. And I thought, what do they talk about when they clock out? What are they doing when they’re just sitting there, and what’s on their mind? That’s when I started getting the process of writing it down. It took about fours weeks to write the screenplay. Which is pretty quick for me; I take a little bit longer.

Q: Were you writing the songs?

Brewer: No, remember I thought I was going to be making it myself — a feature on DV. So I was going to mess with some guys I knew in town, like Al Capone, who even ended up writing some of the music in the movie. I was going to use Memphis rap artists. Those are the cats where I really felt their music. Even more so, you go over to Al Capone’s house, and he was making his rap the same way I was making my movies. He had a studio set up in his kitchen. He had a mic set up in a closet that was filled with padding. He’d have to go in the other room, alright, take your video games and go play outside, because I’m catching you on the mic. And he’d be recording in his home, and I felt that was a very uniquely Memphis story, because Memphis has a history of makeshift studios. You got Isaac Hayes and Otis Redding and Sam and Dave recording in these abandoned movie studios for Stax, and Sam Philips turning an abandoned rooming house into a tiny recording studio where you got Howling Wolf and Rufus Thomas and Elvis and Johnny Cash. So I felt like, wow, here’s the product of that. The tradition still remains. The music was so important.

Q: So it was always centered on music. Were you that confident that crunk would go over so well?

Brewer: I think the thing about crunk that I’ve always liked is that it’s truly the South. What I mean by that is that you look at east coast hip hop, and when it was starting off. You had the east coast hip hop, and that ultimately created break dancing and that led to the big baggy pants, which created a fashion, which created the lingo, which created the content, which created the song, which created the dance, which created…it was this whole circle of creativity. Well, in the South, none of these hard guys are gonna want to break dance in a club. They don’t want to, in their mind, demean themselves by getting down on the ground and spinning around, anything like that. [Laughter.] None of the cats I know in Memphis would want to do that. But they do want to be bouncing to a beat, and so what crunk does is create this thing that in Memphis we call the gangster walk, and it’s just this kind of bounce thing. And you get about eight of your crew in there, and you’re hearing this music, and bouncing against each other. And it’s very sexual, and very violent and very empowering. You don’t know if someone’s going to fuck or fight. And the music feeds that. It’s a very raw, simple music, with a solid bass bottom to it, and a beat. And I feel it’s simplicity came from guys who didn’t have many tools to make that music, and that created the mix tapes that ultimately started  the dance.

the dance.

Q: Craig, are you ready for this to be the new Boyz n the Hood, with all the copycats coming out after?

Brewer: I wouldn’t mind that at all, only because I know guys in Memphis who know what Compton is, and know about Crenshaw, and only know about it through Boyz n the Hood.

Singleton: I think it’s going to be really hard for them to copy this idiom, because the South is so specific. They’re really going to bastardize it if they try to copy it, unless they found people from Craig’s milieu. It would be irony for them to even try, after all the things we tried to get this movie made, and no one would make it.

Brewer: And we’ve already been hearing the rumblings. We already know that there are Hustle projects at studios.

Singleton: They want to do another Hustle and they haven’t even seen it yet.

Brewer: Like, ‘We love your movie. We hear it’s great….’

Singleton: ‘…let’s copy it.’

Q: Hustle hasn’t been released yet — what do you think of all the pirated copies of the movie?

Singleton: My feeling? I try to go out and beat their ass, man, I make sure first of all that nobody gets a clean copy of the movie before it gets out, and after it gets out I make sure that in the major markets, I know exactly where they sell them. So I get certain officials, and certain un-officials…

Brewer: [laughs] The un-officials! I like the stories about these other officials more.

Singleton: …and we go take ’em. I’ve actually run up on people on the swap meets in L.A., and taken my movies. You can sell everybody else’s movies, but you made enough money off my movie, and I snatch ’em. They’re not going to call the police. I hate that. And guys say, ‘Oh, the white man’s making a lot of money on it.’ And I say, man, this is my family, you’re taking money out of my mouth, I don’t give a fuck about the white man. It’s about you disrespecting the work that we’ve done. And nobody wants to see a movie in that way anyway, since it never looks as good.

Brewer: Even worse, it’s lowering a standard for everybody. We worked really hard on sound, and all that.

Singleton: And people keep complaining, ‘why don’t we get these kind of movies?’ And then they keep bootlegging. They’re bastardizing the whole process of it.