BUY IT

AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE!

STUDIO: RKO Radio Pictures, Inc.

MSRP: $13.98

RATED: Unrated

RUNNING TIME: 85 Mins.

SPECIAL FEATURES:

• Commentary by Film Historians Alain Silver and James Ursini, with audio

interview excerpts of Director Edward Dmytryk

• Featurette: “Crossfire: Hate is like a Gun.”

This DVD is part of The Warner Brothers Film Noir

Boxed Set: Volume 02 (Purchase it from CHUD and save your dollar bills!).

Social consciousness films weren’t typically a major element of the studio’s output during the golden age of filmmaking before the great War. Very often, the goal was simple entertainment, at the expense of the action on screen. However, there was an underlying mood of suspiciousness, towards any and all surrounds in people’s habitable places that could have been a direct result of the disillusionment of audiences after the war. On genre that found itself being retread was that of the problem picture. Called ‘problem pictures’ because of their unflinchingly bleak looks at racism, social injustices, and corruption (especially in the political arena, like All The King’s Men), these films aided in telling the stories audiences might shy away from. These various items were brought into the forefront, told against the backdrop of stories that might intrigue or repulse you with their harsh human nature.

One of those stories was the Richard Brooks’ novel The Brick Foxhole, which was centered around a homosexual Marine who is beaten to death by his fellow brothers-in-arms. RKO, who purchased the rights to the story (Brooks would later go on to direct some fine films like Cat On A Hot Tin Roof and Blackboard Jungle), quickly denounced the subject matter (it was a little too hot button, and my, how times never seem to change), and quickly focused on turning the course of narrative developments into that of a treatise against anti-Semitism. Capitalizing on their investment, and noticing the storm clouds of anti-Semitism in Elia Kazan’s Gentleman’s Agreement on the horizon, RKO rushed Crossfire into production, hoping to beat Kazan and Fox to the punch. When a studio does this, many things can come from it (I’m looking at you July 8th’s big film), the worst of all being a crappy film.

So, did RKO’s hunch work?

The Flick

In a darkened room, some punches are flying back and forth. It’s a striking image; the sight of two hefty figures duking it out against their own personal reasons, except that someone’s personal reasons stink to the high heavens. As the punches connect, someone goes down, and he’s out for the count … of eternity. The remaining pair limp slowly out of the room and quietly slink into hiding.

"I have fond memories of Hentai. It’s treated me so well…"

Samuels is deader than dead (he’s defunct!). "Taken a nasty beating" the Corner bluntly states, and it’s up to Captain Finlay (played with a moral center by Robert Young) to figure out the necessary w’s. While he’s still examining the body, Monty Montgomery (the yet-to-be typecast and extremely unstable Robert Ryan) accidentally meanders through the door, only to positively I.D. Samuels’ body. Finlay is curious, but Monty plays it cool and a little saddened by the turn of events his wrong turn has brought. Director Edward Dmytryk capitalizes on this heightened state of emotional distress for all involved in the room, and in typical noir fashion, uses a simple economy of shots coupled against the stark backdrops of shadows and high-profile tension. He’s setting you up for the investigation to come, and he wants you to be ready for the ramifications of all involved.

Finlay can’t figure out why someone would want to kill Samuels. He had no known enemies. He’s done some searching, though, and he brings in Sergeant Keeley (played wonderfully by Robert Mitchum). Keeley’s never killed anyone (he wasn’t with his friends that night), or so he swears, unless it’s the type of killing where you get medals. Finlay wants to pin the murder on Keeley’s ‘friend’ Mitchell, one of the men he can’t seem to account for this fateful night, but like all investigations, he’s gotta wade through the bullshit to get to the cold, hard nuggets of truth, justice, and the Kraken-way. Keeley’s trying easily to keep the heat off of him when Montgomery stumbles into their meeting, adamant upon sticking up for his friend Mitch. This then brings about the Rashomon-esque style flashback of Monty’s recollection of the turn of events at a bar leading up to Samuel’s killing. Monty insists that he was never a part of the horrific crime, but he did have a few drinks with the "Jew boy" and his band of buddies.

"Whoa, whoa, I knew I shouldn’t have

ventured down to the Sex Forum!"

By this point though, it’s clear Monty’s intentions are more than evident. This tell definitely would have him pounced on in Vegas. It wouldn’t stay there, I can assure you that. Finlay, keeping his calm collected visage in check, keeps prodding, but he’s got more than his share of loose ends to tie up before he makes the connection between the group of men drinking with Samuels and the motive behind the cold blooded killing. Monty can’t keep his mouth shut. "Some of them are named Samuels and some have funnier names" he stupidly comments, alluring even more to his bigoted nature and spiteful ways. Finlay, instead of beating him senseless for being so obvious, quietly smokes his pipe, concluding the evidence.

It’s necessary to note the interesting turn of events Crossfire is presenting. These GIs are fresh home from the war, after helping save democracy, and thus, they’re almost untouchable (like the NYPD was after 2001 or a certain party after an election). By having someone in the armed forces, who fought so valiantly against tyranny, be so morally reprehensible and utterly unlikable, Dmytryk, screenwriter John Paxton and producer Adrian Scott are directly challenging the preconceived notions of most American thoughts towards those shielded GIs. This was a very intensive and controversial position to take on (the film could be considered to be very angry towards this position), especially against the biggest army in the world coupled with the feelings of the country on a natural high. This would, unfortunately, become an Elephant in the room for both Dmytryk and Scott a few months later.

"That’s when I said: You can’t close the leads you’re given,

you can’t close shit. You are shit. Hit the bricks pal, beat it,

’cause you’re going out!"

When Mitchell finally recounts his story to Keeley, some of the alarmingly safe aspects change, and we get a more in focus picture of what could have really occurred when all of the boys – Monty, Mitchell, Floyd and LeRoy – had been sufficiently liquored up and revved their engines into a very slippery slope, emotionally. The more Mitchell mentions, the more we discover, about his strange night where he makes easy friends with a woman of the night, Ginny (played with a confident sadness by Gloria Grahame) and her lying husband. After listening to Mitchell’s side of the story, Keeley is unsatisfied, but confident. "The snakes are loose", he says, so he keeps Mitchell under house arrest in the back of a local movie theatre while Finlay is on the prowl. Tensions begin to boil over as Floyd goes up against Monty and Finlay continues to stack the deck against all of the men involved with the murder in their own little ways. There’s got to be a motive, and hate, as Finlay says, "is like a gun."

Crossfire is one of Edward Dmytryk’s most amazing films. Sadly, it also brought about his downfall. As previously mentioned, his controversial take on the armed forces and their motives (although the film does take pains to mention that this is an isolated incident!) angered Congress enough to haul him up against the HUAC (House of Un-American Activities) commission and destroy him to the point of naming names, to which he responded, bringing down producer Adrian Scott with him. Blacklisted for quite some time, he’d find work again later on, but for being involved with the Communist party early on makes him (somewhat) liable for his transgressions. Scott never found work again.

Jimmy knew he’d won when Duff was all alone. And legal.

The mold Dmytryk captures the madness of Crossfire in wasn’t really intended to be a film noir, but budgetary restrictions forced him to be creative. This allowed him to be sporadic in presenting visual events. His keen visual eye is in full force, moving around to give you just a little bit of characters before shifting your attention between the foreground/background elements is a riveting marvel to behold. His use of silhouettes opening the film creates the types of slug-line imagery Samuel Fuller was more-than well known for. As such, Dmytryk shrouds everything in mystery, intensive shadows, and a rather suspicious air. It works tremendously and fits into the mold of film noir like no one’s business. There’s another sequence denoting the passage of time where normal directors would just fade in and out. However, Dmytryk adds extra visual panache by swooshing his camera over Ryan’s left shoulder, editing together a flurry of rushed images that is spectacular as it is exciting. Additionally, Dmytryk’s usage of incredible high-key lighting centered around natural sources (like lamps, overhead lights, desk lights, etc.), adding depth and shadiness to characters, allows the emotional aspects of the picture to be ramped up by the shocking turn of events. By doing so, he makes you focus on the character’s actions alone, because all else around them falls off into space. There’s nothing left to focus your eye in. This is a tremendous visual style to mold, and best of all, it was all really a side-effect from the budgetary restrictions imposed on Dmytryk and his B-picture.

This is a Robert movie all of the way. The three wise R’s, Robert Ryan, Robert Young and Robert Mitchum, all ground their performances into great portrayals, never once going over the top or into an area that you might find sheepishly bad. Ryan was just starting out his career and would play another sadistic morally corruptible man (especially in Bad Day At Black Rock) in his future roles, hence the typecasting you see him fall into later on. At this point, though, Ryan is the sneering bigotry that metastasizes itself into the horribleness of the situation regarding Samuels. His Montgomery is a man who thinks he did the right thing, a man who thinks he can beat the rap and play the field to any advantage underneath his festering visage. Ryan plays it for all it’s worth. Robert Mitchum’s Keeley is a man who just wants to help out, a man who looks out for his buddies. It’s a role for which Mitchum can inject the necessary gravitas into, allowing Keeley to have a swagger that suggests otherwise, even though in the end, he just wants to help. Robert Young’s Finlay is, as already mentioned, the moral center of the film, although every once and a while his innate peachiness (especially equating the Anti-Semitic killing to that of a cruel story involving his Irish grandfather) does get in the way and bog down Crossfire during its most dramatic moments.

"Leonard, if Hartman finds us here, we’re going to be in a world of shit!"

"I AM … in a world… of shit!"

RKO did indeed beat Gentleman’s Agreement to theatres with Crossfire, becoming the first film to focus around those who would cruelly foster Anti-Semitism. It’s still a testament that it still works to this day (better than Kazan’s film), as both a social-consciousness film and a film noir, as all involved definitely brought their A-game to a B-film. Their hunch was correct. This is a damned fine film.

9.0 out of 10

The Look

Presented in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.33:1 (Academy aperture/fullscreen). The imagery appears a little darker than some of the other films in WB’s boxed set (like Born To Kill and Dillinger). Still, most of the film is rather crisp and not hard to make out in between the expressionistic lighting and shadowy characters.

8.0 out of 10

The Noise

It’s best when hanging out at Chevy’s

house to not mention Funny Farm.

Dolby Digital 1.0 Mono. It’s a nice sweet track, filled with gunshots, flesh being punched into the lair of Death, and a hell of a lot of shifty clothes rustling in the breeze. Above all, you can hear it splendidly.

9.0 out of 10

The Goodies

You get a commentary track with Film Historians/Authors Alain Silver and James Ursini (who both wrote a good albeit short book on David Lean) with additional audio excerpts with Director Edward Dmytryk. Ursini and Silver are both incredibly informative and left no pauses as they recount the key films of noir’s classical period, Dmytryk’s trio (this film along with Murder, My Sweet and Corner), the social realism prevalent in films of the era (such as Blackboard Jungle, Crisis and Elmer Gantry) on top of just being a rather interestingly aural time. Occasionally Dmytryk will pop up (most of the time he’s set up by Ursini and/or Silver as in: "and here’s what Dmytryk has to say…") and this is where the meat-and-potatoes of the track really is. He speaks in depth about his dalliances with the HUAC witch trials and their aftermath. He’s got some great things to tell you, and overall, it feels like he’s watching the film with you, even though he was probably recorded just talking about the film. It’s wonderful.

"A little less Norris and a little more Gossett, Jr. on that one."

Finally, there’s a featurette: Crossfire: Hate is like a Gun (runtime: 8:56) which showcases a variety of backstory and history regarding the film and its rush to beat Fox and Gentleman’s Agreement. Discussion ranged from the radical departure of Brooks original intent to please the Hays code (the MPAA before it existed). Dmytryk gets his face time in, and like the movie itself, brings his A-game and slam dunks the proceedings into overtime. He’s sharp as a tack, very lively, and filled to the brim with pertinent information that is interesting as it is fun to listen to. I wished the interview was longer, but c’est la vie. I especially liked the breaking down shooting styles remark (very off-the-cuff) that glossed over how Dmytryk shot Ryan with different lenses, ranging from a 50mm in the beginning to a 25mm to express a subliminal distortion from the rest of the cast. Fascinating stuff, but really mentioned as a throw away!

6.5 out of 10

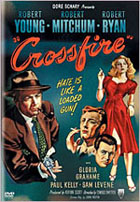

The Artwork

Not the greatest. It feels photoshopped, although the ‘classic’ imagery is strangely painted into a collage of heads, guns, and a giant smoking noir Grahame. The centerpiece tagline fits and gives you an inkling into the films’ own world, but as a whole, I’m not that jazzed about the films cover art. It’s fine for the vintage aspect it presents, but maybe (if there’s a next time) some better original art (if there was any)?

6.5 out of 10