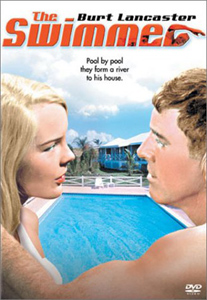

The Saddest Movie Ever Made: The Swimmer

It‘s

It‘s

back! For the triumphant second edition of this column — currently on track

for a blistering quarterly publication schedule — I’ve picked a movie that

couldn’t be more different from the subjects of the first installment. From

Japanese cyberpunk we’re going straight to sixties suburban malaise, courtesy

of Burt Lancaster and The Swimmer.

Don’t worry that I’ve arbitrarily picked this movie from a stack of DVDs. This

one is totally relevant to the situation at hand, and it’s also one of those

near-masterpieces that deserve more love. Based on a story by John Cheever, The

Swimmer is the story of a man who reappears in his old neighborhood,

acting as if nothing has happened, and decides to swim home.

There are

movies that draw you in slowly by putting out a single piece of bait, which is

then dragged step by step back to some place you don’t want to go. The

Swimmer is one of those. It’s definitely not horror, not even what I’d

call a thriller. There’s a mystery here, and a deepening feeling that it’s all

a lie. Think of Blue Velvet, if the whole movie revolved around what caused

Jeffrey’s father’s heart attack. It’s also a memorable, brutally sad movie.

You’re

thinking…what? John Cheever? Not a name associated with great film adaptations.

Then again, neither is Frank Perry, who adapted the story with his wife

Eleanor, who gets screenwriting credit. But Perry’s fascination for dysfunctional

families and Cheever’s with suburbia came together perfectly. In a landscape

where literary adaptations are typically mangled beyond recognition, The

Swimmer is both faithful and adventurous.

Granted,

with a tale that runs a mere ten pages in The

Stories of John Cheever, there shouldn’t be much room to go wrong. But most

of the dialogue, and many of the film’s specific encounters, were invented by

Eleanor Perry for the film. She’s right on the money the entire time, keeping

the tone and intent, but filling out both plot and meaning. There’s evidence to

indicate that Cheever had either Odysseus or Narcissus in mind when he wrote

the story, and Perry’s new opening and the film’s construction cements it.

Summer

fades. Like a lost hero, Ned Merrill appears out of nowhere. He walks straight

onto an old friend’s estate and jumps in the pool as if he owns the place. No

one bats an eye, and a drink is waiting to meet his hand as he rises from the

other end of the pool.

.jpg)

This is

the beginning of a journey across the wealthy spread of Westchester County. Ned

visualizes a crystalline path of water which will take him home. "Pool by

pool, they form a river, all the way to our house. I’ll call it the Lucinda

River, after my wife." For reasons no one can fathom, Ned Merrill wants to

swim home.

But the journey

isn’t as simple as that. Pools mean houses, which mean people. In conversations

with old friends and enemies, there’s this nagging sensation. He stares off

into space and obsesses over the beauty of the day and the water. He’s a

sleepwalker, totally lost inside himself. We join Ned Merrill as his manufactured

reality is in full swing. We don’t watch him create the fantasy life, but we

sure as hell get to watch it crumble.

.jpg)

The

magnificence of The Swimmer is the way that Ned’s own story and realizations

are married to observations about class and race and what happens when

different levels collide. These aren’t grand, shocking revelations, but that

doesn’t make them any less effective. And with every step, Ned moves away from

old, ‘polite’ society and closer to the truth.

Cheever

didn’t have much sympathy for the plight of the social elite, and neither does

this film. In the beginning, the old money families, when faced with Ned’s

awkward appearance, talk about trivialities. Their hangovers, or the tech specs

of a water filter. As he moves on, each encounter reveals more personal details

as the people become less polite. The vulgar new rich talk about their money,

and then it’s broken homes, vaguely antisocial practices and misplaced sexual

desire.

.jpg)

Every

step of the way, it all traces back to some facet of who Ned is, and what

happened to him. When it all comes together, it’s nothing less than the

American Dream gone totally south. Since he appears out of nowhere, and because

so many sequences are touched with the air of dreams, Ned’s failure takes on a

mythic quality. It’s bigger than the fate of a single man.

I feel

like if this movie were made today (see below) that there’d be a shocking twist

reveal to demonstrate that Neddy isn’t all there. But here he comes apart in

layers. The Swimmer is a story told in glances and small movements.

You’ll get as much information out of a couple sideways glances as from any

dialogue. Burt Lancaster is brilliant — golden and muscular at the beginning,

then aged and shivering at the climax.

.jpg)

Everything

isn’t perfect, of course. Here and there, the intentionally oblique photography

veers into absurdity, and a few moments are grandly overplayed, more by Frank

Perry and the editors than Lancaster. In particular, the conclusion is too

grandiose, when a few silent shots would have served perfectly. There are

probably even people who’d write off the film, based on the visual style and

acting technique, which is so late-’60s pop it almost hurts.

There are

also a few moments when Frank Perry and Burt Lancaster seem at odds with one

another. That may be part of the reason Perry eventually walked away from the

picture, leaving the most intense encounter to be directed by a young Sydney

Pollack. (Lancaster was in Pollack’s next movie, Castle Keep, which is

supposedly the film watched by Ronald DeFeo, Jr immediately before killing his

family in a famous Amityville, NY home.)

Those are

squabbles, though. I’ll go on record as saying this is one of the best

marriages of film and prose I’ve seen. In the spectrum of small, forgotten

films, it’s huge.

(I hate to

even touch on this, but it can’t be helped. Rumors have swirled for years about

a remake, and they’ve intensified to the point where Alec Baldwin’s name is

commonly attached to the film. Shudder.)

.jpg)