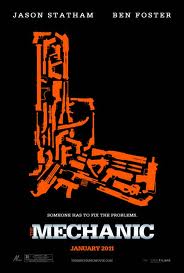

This weekend sees the release of Jason Statham’s newest wam-bammer, The Mechanic, which is a remake of the semi-classic 70’s hitman film of the same name starring Charles Bronson and Jan-Michael Vincent (available on Netflix Instant). The remake, which features Ben Foster taking over for Vincent, follows the story beats of the original very closely, which may explain why original screenwriter Lewis John Carlino shares screenplay credit with remake writer Richard Wenk (writer/director of the delightfully silly 80’s horror-comedy Vamp), even though he did not actually work on the new film. Though this generational crediting is fitting, as this is a bit of a legacy project. The original film was made by the legendary producing team of Irwin Winkler and Robert Chartoff (Rocky, The Right Stuff, Raging Bull), and the old fellas joined their sons David and Bill (Rocky Balboa) on the remake.

This weekend sees the release of Jason Statham’s newest wam-bammer, The Mechanic, which is a remake of the semi-classic 70’s hitman film of the same name starring Charles Bronson and Jan-Michael Vincent (available on Netflix Instant). The remake, which features Ben Foster taking over for Vincent, follows the story beats of the original very closely, which may explain why original screenwriter Lewis John Carlino shares screenplay credit with remake writer Richard Wenk (writer/director of the delightfully silly 80’s horror-comedy Vamp), even though he did not actually work on the new film. Though this generational crediting is fitting, as this is a bit of a legacy project. The original film was made by the legendary producing team of Irwin Winkler and Robert Chartoff (Rocky, The Right Stuff, Raging Bull), and the old fellas joined their sons David and Bill (Rocky Balboa) on the remake.

The remake is directed by Simon West, who blew up on the scene in the late 90’s as one of Bruckheimer’s Angels with Con Air. He followed that success with The General’s Daughter and Lara Croft: Tomb Raider, then sort of disappeared into television for the 00’s, briefly re-emerging pointlessly for the When a Stranger Calls “remake” (I put it in quotes, because they only remade the original film’s prologue). Now he’s back in action with another, significantly more faithful remake. He also directed the pilot for TV’s new superhero drama, The Cape (which is frankly more fun than it has any right to be).

I sat down with West recently for a little tete-a-tete.

CHUD: Forgetting that you’re a filmmaker for a moment, do you have a general opinion on remakes?

West: I’m a bit more hard on sequels than remakes. Cause remakes to me, you know, you can always site the classics. They make Hamlet every year. They make Pride and Prejudice every year. If you’ve got a really good story, why not update it every decade? I wouldn’t want to make The Godfather again, just because… what would you do? But most films from forty years ago, unless they’re beautifully made – well, even if they are beautifully made – there is no harm in it. Because if it’s a good story, why not? Every new generation… they’re never going to watch those films, they’re never going to find them buried on Netflix somewhere, and watch it. They want to go to the cinema and watch a movie on the big screen. So why not retell the story? Look at what’s happening with True Grit. Everyone wants to see it. And it’s up for Oscars. So what’s the big problem? [The remake] might make you go watch the old one. When I saw The Birdcage years ago, it made me want to go watch [La Cage aux Folles]. I probably would have never seen the French film if I hadn’t seen the American one.

CHUD: I think that’s actually happening with The Mechanic already, before the film has even hit theaters. A lot of people I’ve talked to weren’t even aware the new film was a remake of anything.

West: Yeah, yeah. Exactly. I personally don’t think there is any harm in it. I don’t know why people are so reverential. People have been telling the same classic tales for thousands of years. Sagas. Fairytales.

CHUD: I know Winkler and Chartoff had been trying to get this remake off the ground since the 90’s, well before the recent remake craze. I also know they’d previously been planning a much less faithful remake. Had they already moved towards original script by the time you came aboard, or were you instrumental in bringing it back?

West: No, I think out of frustration they’d gone off on all these tangents, and there were so many permutations, I don’t think they new which one to send me. So they sent me the original, the type-written one by Carlino; you could see the literal cutting and pasting they did back then, with cut and glued pieces of paper that were then photocopied. I also hadn’t seen the original film, so I went and watch that. And they’re actually quite different. There’s much more detail in the original script that never made it into the film.

CHUD: Story detail or character detail?

West: Character detail. The character was written much more articulate. But then it went to Bronson, and Bronson is a man of few words. So that all got simplified down. But the structure was really good. Then I was looking around for a [new] writer, and I read the 16 Blocks script, from Richard Wenk, and it was a great script. From page one he did such an amazing job establishing the characters. And he agreed to come in and do [the remake]. And he had eight weeks to do a page one rewrite. He just used the structure of the original, then rewrote every word to modernize it. And we had to re-invent the hits, and also make it much more up to date in action. Cause if you watch the original again, [current audiences] would not accept that kind of action. They are much more sophisticated. They wouldn’t accept that you could break into someone’s house by punching someone in the face and stealing their van. That’d go “What?” But you could do that in the 70’s. And people would accept it and move on. But now you have to be much more intricate. I think [in the original] they got into a house by pretending to be a pizza delivery guy, or a chicken delivery guy. People would just not accept that now, because it has been done so many times.

CHUD: Would you consider the changes that were made to Ben Foster’s character part of that modernizing? Did you feel he needed more motivation for his actions?

West: Yeah. There were holes in the original script. And if you talked to Irwin Winkler about it, [while working on the remake’s script] we’d say, “Oh, we haven’t quite cracked this,” and he’d say, “We never cracked it in the original.” It had to be much more water-tight. People are very good at picking things apart, saying “this doesn’t make sense.” But in those days, people let it go. They were less critical of the plot. Now people look for the holes. Everyone is a film expert. So it had to be much more motivated. So it could hold water.

CHUD: Once you’ve got your script locked, how slavish are you to your storyboards? Do you need to have everything completely planned out?

West: With action you really have to storyboard, because there are so many people involved. You have stuntmen, and you can’t just tell them on the day, “I want that car to be cut in half by another car,” because they’ll say it’s going to take a week to prep. All the action is very carefully storyboarded. And then, dialogue, with the actors – the actors want to do what feels natural. I don’t see the point in storyboarding that stuff.

CHUD: Speaking of the actors. Obviously Jason Statham is coming from a very different place as an actor than someone like Ben Foster. Did you find that you needed to work with them in unique ways in order to get their best performances?

West: Yeah, I see what you’re saying, but that’s the same with every actor. You’ll have a scene with three or four actors in it, and they’ll all have a different technique. So depending on the actor, I might point the camera at them and let them do ten takes, then I’ll point it at another actor I’ll let them do a huge preparation before one take. And then the others, I let them ad-lib and make up stuff. You just have to learn very quickly what it takes to get the best out of each one. That’s the first couple of days [on set]. You’re psychologically analyzing your actors. And you might have done that before the shoot, just talking to them. And you feel where they’re strong and where they need help. It’s not for me to teach them how to act. It’s for me to create an environment in which they can do their best work. So they feel comfortable. Ben liked to have a lot of conversations beforehand; days beforehand. Then Jason liked, just before every scene, just to remind him what his mindset is in that scene. Like, “okay, you just killed your best-friend.” So I tell him where his head’s at, then he’s fine and is off into the scene.

CHUD: Was there any particular scene or sequence that you found difficult to crack while shooting?

West: With a film like this, it’s really all time. These actions sequences, you could spend weeks shooting them, but with a film like this – that isn’t $100 million film – it is always about not having enough time. I had six days to shoot the big end sequence, and then of course, the first day the big car stunt, the pyro didn’t work and the car spun out of control and missed [its mark] completely. So that day is lost, cause it took a whole day to set it up and we had seven cameras on it, and only an hour of daylight. On a big budget movie you just come back the next day and do it again. We couldn’t do that. So then you have to condense the action to fit to five days. Then it rained. So we had four days. And it was overcast those days, so we were actually losing light on both ends of the days. So adding up the hours, we now had just three days to shoot this. It’s time and money that is the only problem.

CHUD: While I’ve still got you here, I’d like to ask you about your Salvador Dali film (Dali, potentially with Antonia Banderas as the painter). Is that actually happening?

West: It’s all financed. We’re just waiting for the final permission from the museum that handles all his work. We need their say-so before we can use [his work]. They’re obviously very protective.

CHUD: Is this a project you originated yourself?

West: Yeah. About four years ago. I’ve had it financed four times. Has fallen apart four times. Now I finally got it financed again. Now we just need the foundation to sign off the final permission, to give us access to the work. Because this is all going to be CG and 3-D and we’re going to go into his paintings and into his head. And it’s going to be a big extravaganza. Sort of Willy Wonka meets Alice in Wonderland meet Dali.

CHUD: Before I set you free… what is your favorite Dali painting?

West: Well, I learned while researching and going over there, that a lot of his early, less famous stuff is really interesting. He had a lot of different techniques. I really love a painting he did that you can only see if you put a bottle in the middle of it. In the 30’s/40’s they made these bottles of wine – or maybe it was a liqueur – that was silver. And he saw this, and he was great with 3-D, and he used to paint in stereo, and he made this picture with a hole in the middle. And it doesn’t really mean anything until you put the bottle in the middle, and you look at the bottle, and that curved mirror bends all the imagery around so that you see a painting. It’s just genius.