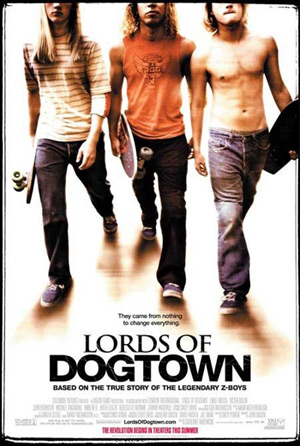

I have met many people who lament that the documentary Dogtown and Z-Boys already covered the first days of skateboarding, so why do we now need a narrative feature version? Besides the fact that almost no one sees documentaries, there’s an important reason for the existence of the new film Lords of Dogtown – it’s trying to build mythology.

I have met many people who lament that the documentary Dogtown and Z-Boys already covered the first days of skateboarding, so why do we now need a narrative feature version? Besides the fact that almost no one sees documentaries, there’s an important reason for the existence of the new film Lords of Dogtown – it’s trying to build mythology.

Every sport has its mythology, its legendary figures and their heroic and groundbreaking feats. Now it’s skating’s turn, and screenwriter Stacey Peralta (who not only directed the Z-Boys documentary, but was one of the Z-Boys himself) and director Catherine Hardwicke have created an impossibly golden endless summer for the pioneers of street surfing to live in, skate in and grow from boys to legends in.

Venice, California, also known as Dogtown, was a seaside slum with a huge abandoned pier that made a great obstacle course for the thrill seeking surfers who congregated there. Among them was a group of younger kids, who didn’t get respect on the waves but whose antics on primitive skateboards inspired surfboard entrepreneur Skip Engblom to start creating better shaped boards, with acrylic wheels that could offer skaters gravity-defying powers. He whipped a bunch of these kids into a team – Team Zephyr, and thus the Z-Boys – and began taking skating competitions all over the place. Meanwhile, a massive drought hit California and the kids discovered that emptied out pools created amazing skating spaces. Slowly and surely these kids became pop culture icons and celebrities, and their lives began to change and blow apart.

Lords of Dogtown isn’t just a sport mythology film, it’s a coming of age film as well, and I think that’s what I liked best about it. As the three main skaters – Tony Alva, Stacey Peralta and Jay Adams – become more well-known they have to figure out how they will deal with the coming money and fame. Each chooses their own path, and as great as the film was when it was about this ragtag group of kids just discovering what they could do, it almost gets better as they scatter and face adulthood in different – and sometimes seriously destructive – ways.

Hardwicke has gathered an impressive young cast. Emile Hirsch follow’s Jay’s journey from confused and angry kid to full blown screw up with complete conviction. Hirsch has a fiery presence that’s hidden in the beginning, but once he discovers punk rock (in a scene so ridiculous and over the top that it had to be intentional) he lets it explode. Victor Rasuk swaggers as Tony, cocky beyond his years and completely real. And Elephant’s John Robinson pulls off the trickiest role, Stacy, with aplomb. Stacy’s the square, the quiet one. Stacy and Tony both sell out – Stacy in the nerdiest way possible, wearing lame jumpsuits and hawking lame products, Tony in the most Elvis way, wearing flashy but lame jumpsuits and hawking himself. Jay, meanwhile, keeps his ethics but loses his way, descending into anger and crime.

The film’s MVP, though, is Heath Ledger as Skip. It takes some time to get past the fake teeth and the egregiously Val Kilmer-esque stylings, but once you get used to it all, Ledger makes Skip breathe. And what’s more incredible is that besides the ludicrous teeth Ledger is acting behind a stringy mane of hair and almost constant sunglasses, plus he’s playing someone who is constantly keeping up appearances of being chill. Ledger’s the beating heart of the film.

Actually, I may take that back. The beating heart of the film could be the amazing soundtrack that’s been compiled – it’s not full of the obvious choices but is still stuffed with the great rock of the 70s, a perfect accompaniment to the world that Hardwicke has crafted. Here the sun is golden, but it’s the setting sun, and the beaches and streets of Venice are gritty. This isn’t where the Beach Boys hang out, and the music rocks accordingly. When Jay skates at his first competition, it’s to Black Sabbath.

It’s that gritty world that makes the movie work. Hardwicke propels us propulsively through the only kind of dilapidated world over which an equally dilapidated Skip Engblom could hold court. And it’s that reality that allows the viewer to relax and enjoy the mythmaking inside. It’s not a perfect film – some of the editing could have been tightened up, and not every performance works (I’m looking at Shia LaBeouf clone Michael Angarano here), but Hardwicke understands teens – which she has already displayed in Thirteen. None of the main kids ever feel false, and the story – even when it’s been sanitized to protect the skaters still living and consulting on the film – feels intrinsically true even when it’s not factually true.

I walked out of the screening of Lords of Dogtown almost bouncing. The film is a rush, a kinetic spectacle that puts you right back into your own 16 year old shoes, when the creation of a counterculture didn’t just seem fun, it seemed plausible. These kids pulled it off, erecting a whole new underground around them. And really it isn’t just the skaters who come of age in this film, it’s their whole underground scene.

8.5 out of 10