Babylon & Pick A Number: Carnivale, eps. 5 & 6

“They shall be carried to Babylon, and there shall they be until the day that I visit them, saith the Lord; then will I bring them up, and restore them to this place.” – Jeremiah 27:22

Samson: “Looks like you didn’t make it out of town.”

Babylon Bartender: “Never do.”

What happens when we die?

Will we simply cease to be? Will we move on to “someplace better”? Will we ride the wheel around again and start over? Or will we find ourselves trapped forever in a dusty, unforgiving, inescapable hell? ….And is there justice to that eventual assignment? Is hell reserved for the wicked? Or just those unfortunate enough to stumble too close to the flames? Not all of us believe in the idea of an Afterlife, but I think we can all agree that dusty, unforgiving, inescapable hells are undesirable places to spend our time – in this life or in the next.

And yet that’s exactly where Carnivale sets up shop for what turns out to be a hypnotically-compelling and disturbing hour and a half of television. Babylon and Pick a Number offer us a glimpse at a special sort of horror – the kind that doesn’t jump out at you, but instead curls itself up slowly in your gut; icy and irresistible. These two episodes tell one story, and so it feels appropriate to tackle them as one column. To me, at their core, what these two episodes ask and then answer is a very simple, very troubling question: Are we the masters of our fate? Are we the captains of our souls? The answer Carnivale seems to give is “no.”

Babylon and Pick a Number function as two halves of the same haunting story, and they represent Carnivale’s best efforts yet. If the show maintains this level of quality and downright-spookiness I’ll be a very happy man. But before we launch into the substance of the episode lets talk about themes and references for a moment.

In the column for After the Ball I talked about the possible connection between that episode and Tolstoy’s story “After the Ball Is Over,” as well as the potential connection between the show’s titular Carnivale and the philosophical/theological concept of “carnival” and/or “carnivale.” I was fairly convinced that Knauf and Co. were intentionally referencing Tolstoy and potentially riffing on the Bahktian conception of carnival on the sly during After the Ball, and I was pretty goldurned impressed by the quiet intelligence and the writerly-chutzpah that I thought I saw there – not just because Tolstoy and Bahktin aren’t typically topics that television shows allude to, but because Knauf and Co. don’t seem to care whether or not I/you/we grasp their allusions and their references. There are no explicit references to Tolstoy in After the Ball, just implicit ones. There is no mention of the notion of carnival/e in the text of Carnivale, but there is subtext to that effect. Doing this kind of stuff takes a lot of work, and doing it this well – this sneakily – takes a lot more work. So is it intentional? Are those references meant to be teased out by people like myself, people with too much free time and not enough distractions?

Based on Babylon, I’m saying yes. Remember this charming Bible passage, quoted in full by Brother Justin during the events of Black Blizzard?:

“If anyone causes one of these little ones—those who believe in me—to stumble, it would be better for them to have a large millstone hung around their neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea. Matthew 18:6-7

I suggested last week that Carnivale’s writers had selected that Biblical passage to create questions in the mind of the audience about Brother Justin (is he referring to himself as God?) and to reference the migrant children who end up “stumbling” by the end of the episode. But it’s possible that there’s much more going on here than that. And it confirms to me that Carnivale is a show that’s interested in engaging with its audience on multiple levels. Allow me to explain:

In the Book of Revelation – the book of the Bible that Justin quotes from during Babylon – the large millstone that appears in the book of Matthew makes a second appearance during the portion of the Book dealing with…wait for it… the destiny of Babylon. An Angel appears to John and throws “a boulder the size of a large millstone” into the sea:

“And a mighty angel took up a stone like a great millstone, and cast [it] into the sea, saying, Thus with violence shall that great city Babylon be thrown down, and shall be found no more at all.” – Revelation 18:21

This action mirrors (yay! Mirrors!) the instructions that Jeremiah gives to the quartermaster in the Book of Jeremiah – instructions that relate to the city of Babylon: Jeremiah had written on a scroll about all the disasters that would come upon Babylon–all that had been recorded concerning Babylon. He said to Seraiah, “When you get to Babylon, see that you read all these words aloud. . . . When you finish reading this scroll, tie a stone to it and throw it into the Euphrates. Then say, `So will Babylon sink to rise no more, because of the disaster I will bring upon her. And her people will fall.'” (Jer 51:60-61, 63-64). Either the juxtaposition of these biblical passages and imagery is entirely unintentional and thus spectacularly coincidental, or Knauf and his writers specifically linked the Matthew quotation to the Revelation quotation. In other words, Brother Justin’s quote from Matthew in Black Blizzard leads directly into his quote from Revelation in Babylon, just as Black Blizzard leads directly to Babylon.

Now examine this portion of the Book of Psalms, also concerned with Babylon:

“O daughter of Babylon, who are to be destroyed; happy shall he be, that rewards you as you have served us. Happy shall he be, that takes and dashes your little ones against the stones.” Psalm 137:8-9

This could be the mescaline talking, but this particular section of scripture reads as a near-rebuttal to the words from Matthew that Brother Justin quoted in Black Blizzard. Coincidence? Probably, in this case. The larger point remains: either spectacular coincidence or serious thought was involved here, and I’m inclined to think it was the latter. But to what purpose (if any)?

The recurring image of the millstone reminds me of the pull of fate; Justin and Ben’s respective fates are like millstones around their necks, drawing them toward destinies they don’t understand.

Other thematic stuff: We learn via conversation between Lila and Lodz that Austrian chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss was recently assassinated by Nazis, which places the carnival firmly in the summer of 1934. I’m not sure whether this is just some period detail thrown in to ground us more firmly in a specific time and place, or whether this is a “story seed” designed to indicate that Carnivale will be tackling themes of fascism and/or using the rise of Nazism as a backdrop for its drama, present or future.

So what happens in Babylon and Pick a Number? Shockingly, quite a bit. Thus far Carnivale has heaved its plots along with all the speed of a geriatric tortoise, its episodes a study in atmosphere and murky, surreal imagery and encroaching dread. In Babylon and Pick a Number things escalate significantly: the carnival sets up outside of the oft-mentioned mining town of Babylon. There’s something deeply wrong about Babylon, a kind of nebulous unease that seems to hang over everything (the music in this episode helps tremendously – its wonderful stuff). That sense of unease only grows as the populace of Babylon – all men, all filthy, most of them curiously vacant-eyed – visit the carnival that night, and filter through the various rides, exhibits and games with the grim, determined shuffle of a pack of zombies.

As this is happening, Ben drunkenly ends up in a closed mine (how he got there, whether he’s even actually in there and not just passed out in front of it, are questions that have no answers) where he experiences a vision of Scudder and of the word “avatar” written over and over.

Back at the carnival, Samson senses the bone-deep wrongness of these strange men and orders the “cooch dancers” not to take their panties off (Samson calls it “the blow-off,” another instance of great “carniespeak”). Given what we’ve seen of these miners you’d think that Ma and Pa Cooch would listen to him, but Ma persuades Pa to let Dora Mae do the blow-off anyway, and the sight of her exposed lady parts (this isn’t TV, this is HBO, so we get a long look at them too much to my surprise) drives the miners into a sudden, zombie-esque frenzy.

Left to care for her injuries alone, Dora Mae is taken and hung, the word “Harlot” carved into her forehead.

That, in and of itself, would’ve made for a nicely unsettling story, but the narrative continues in Pick a Number. We start out getting a glimpse into Jonesy’s past (he had his knee smashed with a baseball bat by a smirking older man wearing the same team hat that Jonesy wears, which suggests that Jonesy was involved in some shady dealings) and things get even creepier as we learn the secret of Babylon and of Scudder’s connection to the town, receive another tantalizing glimpse of past events/the show’s mythology, watch the carnies exact vengeance for Dora Mae’s death, witness the death of Brother Justin’s faith, and end on an image that’s powerfully, effortlessly haunting; frightening and sad – the “ghost” of Dora Mae staring down at Samson from the window of a building in Babylon, then being drawn silently back and out of sight by the grubby, spindly arm of a Babylon miner.

This is Carnivale firing on all cylinders, and its exciting stuff. So let’s talk about some of it, and see what there is to see.

Samson: “You gotta give me something to tell them.”

More ambiguity over the existence of Management in these episodes, and over Management’s motives. Why IS Management directing the carnival to go to Babylon? I’m assuming it’s so that Ben can have his vision quest, but does he/she/it know what’s happened to the mining town? Worse…does he/she/it know what will happen to Dora Mae? Again I’m struck by the way that Management can stand in for God over the course of these episodes – metaphorically speaking. Mgmt. can also stand in for the devil, but the God metaphor works nicely. A “supreme being” (in terms of the microcosm of the carnival at any rate) that doesn’t appear to have physical form and so requires faith in his existence. A being that sends out directives through his high priest, Samson, and sees them carried out by his “people.”

So, metaphorically speaking, why would a “loving” “god” send his people to a place like Babylon? The moral ambiguity continues here as well.

Also continuing in this episode is the strange, drawn-out dance between Ben and Lodz. Ben starts out in Babylon informing Lodz that he’s figured something out – that Lodz doesn’t know half of what he pretends to know. Clearly Ben thinks that Lodz is up to something, and he’s right to think so. Lodz is just plain creepy, even when he’s playing wanna-be-Obi Wan to Ben’s Luke Skywalker. During Ben’s vision quest, Lodz sits patiently outside the caved-in mine, awaiting Ben’s arrival. It’s unclear whether Ben is laying at his feet that entire time, or whether he’s wandering around in the cave. They end where they began, with Ben telling Lodz to find his own way back to camp, and with sightless Lodz doing just that, confirming that his quests for assistance are probably an act. Possibly interesting detail to note: When we first see Lodz here he’s shaking in bed, a victim of what Ben calls the “clanks” and what I assume is the DTs. Only, last I remember, Lodz was well-stocked in the alcohol department. Is it possible that he’s drying himself out intentionally? Preparing himself for something?

Sofie spends the episode making a potentially Sapphic friend in cooch dancer Libby, Dora Mae’s sister. Sofie and Libby’s budding friendship and/or flirtation make this episode kinda poignant in a way. Libby draws Sofie from her shell some, and its obvious there’s attraction there which, red-blooded American male that I am, is never precisely a terrible thing. You know? Looks like I was wrong about Ben and Sofie being romantic interests for each other at least for the time being. Between these two and the sorta-queasy attraction between Ben and Ruthie they’ve got their hands full. Its nice to see these characters growing in depth. Libby’s revelation that she lost her virginity at “11…well, 12” is a quietly tragic one, aided enormously by Carla Gallo’s performance.

The mood darkens further as soon as the carnival crowd enters Babylon that night. Sofie and Libby run into the World’s Creepiest Projectionist, who has the air of a serial killer on his night off. The silent they watch, by the way, is Intolerance by DW Griffith; a film that features a recreation of Ancient Babylon as well as the notion of a generational struggle where past acts have influence on future events (or, under Fatalism, where future events have an influence on past acts – keep this in mind for later). The resident of Babylon that the carnival met on the way into town is also apparently the town’s bartender. When Samson notes that he didn’t make it out of town the bartender smiles and says “never do.” Hannah’s delivery sells the unstated implications of that exchange perfectly, subtly. By the time the carnies are really cutting loose, dancing and drinking, a group of silent, lantern-bearing men has gathered at the window. There are no special effects here, and no jump scares, just effective, slow-rising unease.

That unease increases and becomes fear once the residents of Babylon finally come to the carnival. Their approach is filmed like a scene out of Night of the Living Dead, the horde of miners faceless and in shadow as they silently pour through Carnivale’s gates. More than anything, that’s what these miners remind me of – zombies. Many of them carry vacant, dim-witted expressions on their faces, many of them move like sleepwalkers, shuffling along past the various exhibitions. The show little emotion, until the moment when Dora Mae’s cooch dance goes too far and sends them into a decidedly zombie-esque frenzy.

So are they zombies? Not in the literal sense, at least not so far as we see. But maybe they are in the figurative sense. We learn from Hannah’s bartender that Babylon may have become cursed thanks to “Hack” Scudder, who we know is probably Ben’s babydaddy, and who probably had Ben’s healing power. We know that Scudder killed one of the miners, that the mine subsequently collapsed, that afterward the miners all came back, and that they “keep coming back.” This all seems pretty Pet Semetary to me. Those who die in Babylon are cursed to come back in Babylon (as “ghosts” or as people? Its unclear) but they seem to come back “wrong.” Mean. Violent. Shuffling. Zombie-esque. Is that because Scudder’s power was spread over so many people? Why can’t they leave? This is also unclear. And somehow that lack of clarity ends up working to the show’s benefit. Not being able to understand what’s happening fully ends up making it more frightening.

And speaking of the mine….

Carnivale drapes itself in a lot of Judeo-Christian symbolism – the Bible quotes and signifying names and whatnot. But Is Carnivale an explicitly Christian narrative? Not according to Babylon. During Ben’s Long Dark (caved-in) Night Of The Soul he follows what might actually be Scudder, or what might be a “ghost” of Scudder through the passages and stumbles upon a section of the mine where “Tavataravataravataravataraetc.etc.etc.” has been carved into the wooden beams in one unbroken string of letters. Ben hurriedly writes “Tavatara” on his arm to remember these letters, but he gets it wrong (or so I think). What he’s really seeing here is the word “Avatar” or “Avatara” written over and over.

The appearance of the word avatar and the suggestion that “in every generation exists a creature of light and a creature of darkness” suggests that what we’re watching may be a kind of monomyth – a root cause of/explanation for the world’s religions. Hinduism is generally considered one of the oldest organized religions in the world, and the concept of “avatars” originates with them. The concept of Hindu “avatars” involves the gods descending to earth and assuming human form – something we already suspect is the case on Carnivale thanks to Samson’s opening monologue (a creature of light and a creature of darkness, born to each generation, sounds a lot like “avatars” of Good and Evil). Note that this concept is similar to (but not the same as) the idea of Christ being both divine and human. Perhaps, in the world of Carnivale, the “avatars” of light and dark inspired the Hindu concept of avatar. Perhaps the existence of Hell and Heaven’s representatives on earth is meant to account for the stories of Vishnu and Christ and Mohammed and Buddha and on and on anon (Was Herod a “creature of Darkness”?).

That’s heretical, even blasphemous, but it also feels right. Ben is an avatar. Justin is an avatar. Just as Scudder is (was?) an avatar. This just makes sense. What I don’t understand, as Scudder puts it to Ben during the episode, is “what that means”. How many of them are out there? Just two? Or can there be many avatars? Was Lodz perhaps once an avatar? That would definitely explain his interest in Ben. What are the purposes of the avatars? Are they meant to clash in order to thwart Armageddon? In order to “define” each generation? In order to settle some longstanding bet ala Job?

Beats me.

Now let’s talk for a second about the idea of Apollinarism. What’s Apollinarism? Apollinarism is the belief, first articulated by Apollinaris of Laodicea, that Jesus Christ had a human body and a human “lower soul” (i.e. – human emotions), but was possessed of a “divine mind.” Apollinaris also taught that human souls are derived from the souls of their parents.

Why is this gobbledygook relevant to Carnivale?

Well, for one, a prominent character on the show is named…Apollonia. For another, the idea of “avatars” dovetails nicely with the (widely held as heretical) Apollinarian idea that Jesus had a human body, human emotions, and a “divine mind.” Finally, Carnivale has all but stated outright that Scudder is Ben’s father. We’ve learned that Scudder had superpowers. It’s a natural leap then, to the idea that Scudder passed those powers along to Ben in a way comparable to the Apollinarian idea that the souls of children are created from the souls of their parents.

Kooky sh*t, right? And yet it all makes a suspicious amount of sense to me.

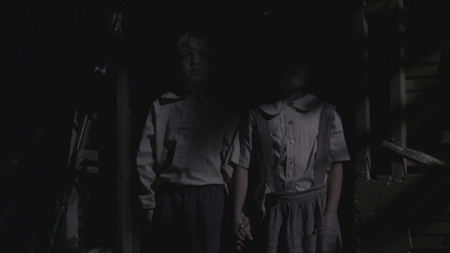

I haven’t talked yet about Brother Justin and his side of the story, because he’s largely absent from Babylon, popping up at the beginning and the end of the episode to quote some seriously heavy scripture about the titular city as he kneels in the ashes of the Dignity Ministry. But Justin appears slightly more often in Pick a Number and, as I’d suggested might be the case in last week’s column, the loss of his new church and the deaths of the migrant children have broken Justin’s faith. They also seem to have activated a whole new set of waking visions. Justin sees two children (are these the same children we glimpsed in the dreaming visions from episode one?) as well as a totally-unclear stick/handle/something or other which falls from the ceiling as he prays to himself. What the heck is that thing?

“Jesus, full of the Holy Spirit, left the Jordan and was led by the Spirit into the wilderness, where for forty days he was tempted by the devil.” – Luke 4:1-2

Justin cites Luke 4:1 here, a passage regarding Jesus’ time spent in “the wilderness,” resisting the temptations of the devil for forty days. By the end of these episodes he’ll set out into a “wilderness” of his own, attracting the attention of a radio personality in the process. The question is: once out in the wilderness will he resist the temptations of the devil? Or will he succumb?

I think we already know the answer to that one.

Speaking of visions – Ben experiences a doozy while wandering around the mines/laying unconscious at Lodz’s feet. He leaps into WW I, suddenly in the shoes of the soldier we’ve seen. We again see the bear (which you’ve helpfully noted wears a hat that says “Bruno” in Russian. I’m pleased that my initial translation – ‘Bear! Oh no!’ is at least phonetically similar to the actual meaning). But the most intriguing portion of Ben’s vision arrives when a younger-looking Lodz appears, suggesting that Lodz’ knowledge of, and dealings with, the “avatars” goes back to the first World War, and suggesting further that he and Scudder may have been friends/may have traveled together/may have joined the carnival at the same time. Also, the guy in the bear suit (Carnivale has a big budget, but not big enough for real bears I guess) apparently belongs to Lodz. Whether the bear is literal or metaphorical is another question. I just hope it doesn’t try to go down on anyone ala The Shining.

Lodz also has his eyes here, which means that he traded them at some point between the events here and when we first see him in the present day. As for the rest of Ben’s cool/surreal/spooky out-of-body (?) vision experience, I have no idea what we’re supposed to take from it except that this memory/history/moment has massive significance to the larger story.

As mentioned above I suspect that Justin and Ben represent the “avatars” of Light and Dark, and that their actions are self-directed, meaning that neither God nor the devil are telling them what to do. At the same time, the fact that Ben and Justin are “avatars” by definition means that they embody aspects of God and the devil and are perhaps “fated” to assume the characteristics of those roles. If Justin holds the “spark of Darkness” inside of him, then he can arguably struggle against it, but he can never be free of it. And if that spark is truly innate – if it is similar to the Apollinarian idea of the “divine mind” – then he can’t really even struggle, because his “higher mind” is already, by its very nature, a thing of “Darkness.” In addition, both Ben and Justin have been receiving visions, and those visions have been revealing themselves as glimpses of future people, future events, future places. The “choices” that Ben and Justin have made have led them, inexorably, to glimpse these visions in their “real,” waking lives, indicating that Justin and Ben are to some extent “fated” to walk the paths they are walking.

In a sense, “fate” is the figurative Millstone referred to in the Biblical passages above, dragging these characters along to where they must be, shaping them to be what they must be.

Paging Agent Cooper…

A brief note on the burial of Dora Mae: The ritual of giving the dead gifts to carry with them to the other side is an ancient one – you can see it in the burial rites of the Ancient Egyptians. It’s interesting to learn that Samson was a strongman at one point. Does he still have that strength? Management’s gift of a watch that never needs winding seems like a cruel joke, considering that Dora Mae is apparently doomed to wander Babylon for all eternity. But I wonder whether there’s a component of pity and sympathy to the gift as well. Is the watch meant to help Dora Mae hold on to the concept of the passage of time? To help mark the days until God will visit them, “bring them up, and restore them to this place”?

Despite all of the misdirection so far it’s pretty obvious that Management is going to have to show it/him/herself eventually, and I’m looking forward to seeing whether he/she/it bothers to explain itself, or whether it will simply ask “Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth?”

The idea of the “Carnie Code” is wonderfully Old Testament in execution (no pun intended) and further serves to underline the sense of Fate and Fatalism that underline these episodes. Hannah’s murderous bartender receives three literal “shots” at death via a kind of Russian Roulette when he picks the number “3” and is forced to stand there as a gun with one bullet chambered is clicks 3 times. Chance, or luck, or something else spares Hannah’s life, but there’s no escaping death for him. Samson returns to town alone and shoots him in the face (hardcore, Samson), ensuring that Hannah will spend an eternity haunting Babylon’s streets. You can argue that Samson exercises free will in the face of fate here, because he chooses to kill Hannah once “fate” (ie: the gun) spares his life. But as with previous episodes there’s a real sense that life in the world of Carnivale consists of a series of tumblers sloooowly falling into place. Hannah’s from Babylon, after all. And as he tells Samson, he never does manage to make it out of town (a detail that confuses me).

And speaking of confusion…

We get a lot of partial beginnings-of-answers in Babylon and Pick a Number, but what we don’t have answers for are the mystical shenanigans that serve to power the narrative of these two episodes. Everything about this place and its population of spooky dudes is ambiguous. We’re given very little in terms of outright explanations, and as mentioned somehow this ends up making everything that much creepier. We’re told that Scudder killed a man named “Buttridge” (heh) and that after the miners attempted to bring Scudder to justice there was a cave-in which killed all of them. But then “they came back, and they just keep coming back.”

What does that MEAN? Are these miners “ghosts”? Not traditional ones, since they interact with the living and lay their hands on physical objects without difficulty. Are they zombies as suggested? Possibly – they sure act like zombies but we never see them dine on flesh and there’s obvious intelligence to some of them. When Dora appears at the end of the episode she’s unmarked – her forehead no longer bears the word “harlot.” Is this because she has literally risen from the dead, healed of her past injuries? Is this because she is now a spirit, and so unmarked by life’s physical scars?

And if it’s the dead that are trapped in Babylon then why can’t John Hannah’s character leave before he dies? And if Hannah is stuck there, then why aren’t the carnie-folk?

There’s no answer, and, interestingly, no real indication of how the life that these miners lead is different from the life that the majority of people in Depression-era America lead. That’s the thing – the people of the Dust Bowl are already living in a dusty, unforgiving, inescapable hell. They don’t need Babylon to feel like they’ve been trapped and damned. All they need to do is look around. And the people of Babylon aren’t truly all that different than the collection of self-interested, brutal men we’ve been witnessing all along.

What really makes Dora Mae’s fate especially haunting, especially sorrowful, is her solitude. The members of Carnivale’s carnival may wake up with grit in their teeth, may not have any coin in their pocket, may deal with unsavory folks and experience horrific tragedies – but they do all this together, as a ramshackle family. They stand united.

Now and perhaps forevermore, Dora Mae will stand alone.