Tipton and Black Blizzard (Carnivale S1, eps. 3 & 4)

“Heal the sick, cleanse the lepers, raise the dead, cast out demons. Freely you have received, freely give.” – Matthew 10:6

Brother Justin: “Who has more faith in God than those who have borne witness to His fury?”

That’s an excellent question, Brother Justin. In the face of tragedy, of the unjust and the inevitable, the human race has always turned to religion for answers and – barring that – for comfort. And it is eminently arguable that faith is strongest in those of us who are undergoing suffering, those who are desperate. For the Depression-era migrants and farmers of Carnivale, that desperation is a powerful fuel to the engine of faith. Tipton explores that desperation, that strain of faith, through the eyes and through the actions of its two mirrored leads – Brother Justin Crowe and Ben Hawkins as they ascend to “Prophet”-like status. When people depend on a prophet to bring sign of God’s presence in this world those prophets assume a truly awesome responsibility. They command the faith of the desperate, and there’s no faith more easily abused. It’s interesting to watch Justin and Ben’s respective responses to this responsibility. Justin embraces it with a zeal that’s messianic, filling the migrants with a passionate belief in their status as God’s people, and drawing a perhaps-intentional comparison between them (families who “wander in the wilderness”) and the tribes of Israel (thus also drawing an eyebrow-raising comparison between himself and Moses). Ben sweats every moment of it; unsure, uncomfortable. There’s certainly something Christlike in the way that Ben is crowded in by people clamoring for his healing touch, if not Biblically than certainly in terms of how musical theater has interpreted Christ’s story. I half-expected him to launch into an Andrew Lloyd Webber number and yell “There’s too many of you!” This dichotomy, and the confusion of morality in both these men and the people that surround them, make Tipton worth watching.

The question is: do you want to keep watching? The time has come to weigh in and cast your vote on whether to “Cancel” Carnivale all over again or “Renew” it and continue watching the show together. It’s my opinion that Carnivale is worth sticking with, but it’s your opinion that matters here. If you haven’t had the chance to form an opinion yet – if you missed my write-ups on Milfay (ep. 1) and After The Ball (ep. 2) – you can catch up by clicking the provided links. If you’d like to drop me a line for any reason you can do so at WhatIsWater@gmail.com. And if you’d like to join my tiny army of followers on Twitter you can do so by clicking this link. So. Go ahead and vote your conscience in the comments below or on Chud’s venerable message boards and let me know: should Carnivale be Cancelled or Renewed?

One more thing before I dig in: It’s come to my attention that Debra Christofferson (Carnivale’s Lila the Bearded Lady) and Daniel Knauf (Carnivale’s creator/writer/all-around apparent mad genius) both took the time to read and comment on my half-crazed ramblings re: After The Ball. This pretty much blows my mind. Should Ms. Christofferson and Mr. Knauf decide to pop back in this week I’d like to say thanks for taking the time to sift through my verbiage. I’m enjoying the show, and it’s evident that those involved were passionate about the material. It’s very strange and very cool to experience firsthand how technology enables communication between artists and their audience.

Now that we’ve cleared that stuff outta the way let’s talk some about Tipton. As in the first two episodes, not much really “happens” in Tipton as far as the overarching plot of the show goes (though hindsight may change my impression here). Instead Tipton continues to deal in Carnivale’s general fondness for opaque spookiness and deep-dish moodiness while dropping a few more breadcumb-sized bits of information about the larger story. The episode gives us a window into the sort of faith that Carnivale is dealing with/will deal with, and it conveys this in the form of two very-different-yet-very-similar spiritual settings: the apparently-genuine conviction and outreach efforts of Brother Justin and his newly-formed Dignity Ministry, as well as the far more cynical exploitation of honest faith by the members of the show’s titular Carnivale. This mirroring (yes, more mirroring) suggests some interestingly-unclear things about Carnivale’s conception of “faith” and “religion.” It further underlines the presence of decidedly non-Manichaen characters in a Manichaen setting (or, to put it faaaar less pretentiously: Carnivale continues to be a show about the clash between “Good” and “Evil” using characters that are neither “Good” nor “Evil” in the Black and White, binary sense of the words). That’s what interests me most about the show – not the quasi-Lynchian/Clive Barker-esque visions/jarred fetuses, although I’m a sucker for a creepy fetus in a jar (this marks the only time in my life that I will ever type those words). The carnival of Carnivale is chock-a-block with double-dealers, suspicious characters and potential dangers. Yet this troupe of rapscallions seems (“seems” being the key word when it comes to Carnivale) to be the de facto “protagonists” of the show – allies of or agents of “the forces of Light” that must (?) continually clash with “the forces of Darkness.” The carnival spends its time during Tipton trying to dupe the rubes out of their hard-earned cash by promising them something that is arguably deeply cynical, even sinful: fake “healing” in a time where “healing” (of the body, of the wallet, of the community, of the land itself) is what’s desperately needed. Does granting the illusion of that healing provide an arguable “good” to the community of Tipton? Is such a thing arguably comparable to the sort of “healing” that religion gives us generally? Or is the blatant hucksterism on display here all that matters from a moral point of view? I don’t know that there’s an answer to that question in the larger, cosmic sense, but I tend to think we’re meant to be conflicted about this as far as the show is concerned.

WE know that Ben Hawkins can actually heal people, and the folks who come to see “Benjamin St. John” in action clearly want to believe that Hawkins’ gift is real. But the folks of the carnival (with the exception, I think, of Lodz) don’t know that Hawkins has a gift and, once they become aware of Hawkins’ reputation via Jonesy, clearly do not believe that such a gift is real. This makes their actions deeply predatory and lends the whole operation a sleazy, opportunistic air.

By contrast, Brother Justin Crowe and his po-faced sister Iris are clearly working toward something that I personally would consider a deeply-positive spiritual and societal goal – an effort to feed, clothe and care for a population that has been forgotten or, worse, intentionally ignored. Sure, Justin has the tendency to KILL PEOPLE WITH HIS MIND when he gets upset (kind of a character flaw), but he’s also invested in achieving a demonstrable Good here (at least as I’d define it – those of you who worship at the altar of Ayn Rand will disagree, and will be unfortunately aggressive and weirdly-conscienceless in your disagreement). Despite being utterly convinced that Brother Justin will, at some point, embrace “Darkness” I would say that his mission represents the clearest form of “Good” that Carnivale has offered us.

This is kinda knotty stuff, and I’d really like to know if it was intentionally constructed this way. If so, it’s masterfully done and I’m impressed by the thought that’s gone into shaking up my expectations of a “war between Light and Darkness.” If it’s not intentional? Well, that depends, I think, on whether you think about what authors do or don’t intend, and whether you think about what artists are trying to convey in their art. For me (and I emphasize that this is personal opinion – your mileage may and probably will vary), if Carnivale’s moral waters are UNINTENTIONALLY muddy than I lose a good amount of desire to engage with it on the level that I want to engage with it on. I’d savor an opportunity to discuss this stuff with the show’s writers, but I respect the strange osmosis-of-meaning that Art creates in the mind of each person who views it, and I suspect that the show’s writers would rather we debate exactly these sorts of questions than step in and clear things up for us.

If I’m being honest, there’s precious little here that hasn’t already been effectively alluded to (the “cost” of Ben’s gift, as for instance) or already executed in a slightly different form (the opposition that Justin encounters here from Glenn Shadix’s Val Templeton is a magnification of the opposition he’s already encountered in the form of Carol Templeton – a point driven home by identifying Val as Carol’s cousin). As such, I honestly don’t have much to say about Tipton outside of some general comments and some wonky rumination. Lucky you. I’ll note that its great to see a number of well-known character actors popping up in this episode, from Shadix (a wonderful screen presence who, much to my surprise and dismay, died in September of 2010) to Michael O’Neill, to Charles Robinson (aka Mac from Night Court) to Matt McCoy, former star of Skinemax “thrillers” turned frequent (and frequently very good) guest player.

Aspects of Tipton that are interesting/cool/whackadoo/tantalizing/whatnot:

1) Ms Donovan makes clear what you and I had already guessed – that there are “rules” in place governing how Ben can use his power (hard to Believe Ben wouldn’t have figured this out as well, since he was right there when the crops around him died). Further contemplation brings further questions – was Ben responsible for making his mother’s home a barren place through the use of his power? Was the Oklahoma Dustbowl of Carnivale created in the same way? Does Donovan’s knowledge of the rules mean that Henry Scudder possessed the same abilities as his son?

2) For his appearances as “Benjamin St. John” Ben is given Scudder’s old tuxedo to wear and several characters remark on how its as if they’re seeing a ghost, which does a nice job of further confirming Ben’s heritage without giving us a scene where someone yells “You’re his son!” More interestingly, Lodz appears to have arranged it so that Ben will wear Scudder’s clothing, and there’s something quasi-talismanic about this act – an act that reminds me, for some reason, of the game of “Assumption” from the most-excellent Tim Powers book “Last Call”. The game of Assumption is played utilizing a Tarot deck, and the winner of the game “assumes possession” of the loser’s body and soul (this basic idea was repeated/homaged by the writers of Angel for their episode The House Always Wins). There’s a sense that Lodz is trying to test/activate/possibly Assume Ben’s powers here, and that sense is confirmed in the next episode.

3) As mentioned above, Justin and Ben’s lives continue to mirror one another in interesting ways. Both characters head religious services of different sorts, both wear ‘vestments’ in their respective churches (or ‘houses’ if you will) and both services visually reflect each other to some extent (see above). Both Justin’s migrant ministry and the carnival run into opposition to their presence in town from men who don’t want “the wrong kind of people” hanging around. The migrants and the members of Carnivale’s carnival also mirror each other – both groups of societal “outcasts” who are unwanted by the men who profess to watch over the communities they encounter. This consistent mirroring suggests that just as Ben gets a little more context on his abilities and his heritage in this episode (he can give life, but he needs to take it from somewhere else – a concept neatly illustrated to us already in the first episode – and he’s almost certainly the son of Henry “Hack” Scudder), so Brother Justin may have a similarly-revelatory experience in the near future. You don’t need to pick up on these things to enjoy Carnivale, but they definitely enrich the experience of watching the show, and they’re key, I think, to appreciating how much work has gone into the show on every level. Carnivale may not be interested in moving quickly (or hardly at all) as a narrative, but that doesn’t mean that the narrative here isn’t painstakingly-built.

For instance: the funeral service that we witness at the opening of the episode is the same service that Ben saw in the first episode, courtesy of his visions. Whether they filmed the season all at once and then went back to insert footage from later episodes into the premiere, or whether they shot the images at the time of the premiere and then made a point of including those images in future episodes is irrelevant. What matters is that Carnivale clearly knows where it’s going in terms of its own mythology and that encourages me to want to travel along with it.

That said, Tipton’s geography kinda confuses me. Hasn’t the carnival moved on somewhat considerably? Then why is the girl that Ben healed in the first episode in Tipton when Ben and Jonesy visit? Shouldn’t she be miles back by now? Or has her family been traveling to catch up with the carnival in the wake of her healing? If so there’s no indication here that that’s the case. Granted, Tipton and Milfay are in adjacent states but it’s a bit odd. Also a little confusing (or just evidence that I haven’t been watching closely enough): Ben finds Big Sky Farms and locates a woman named Rebecca Donovan who knew Scudder, and who might have been his lover. She tells Ben that she never met Ben’s mother, but the picture Ben has clearly shows his mom in front of a truck with Donovan’s former property’s name on it.

The ending of the episode – with the town’s Sheriff storming into the carnival’s revival tent and demanding that they heal his mother – aka Rebecca Donovan formerly of Big Sky Farms. Ben’s evident relief when Ms. Donovan refuses to be healed highlights what’s swift becoming one of the most important distinctions between Ben and Justin, mentioned at the start of this column. Justin’s abilities seem to manifest near-unconsciously at this point, and when they do he accepts them as signs from God, and doesn’t question them. Ben is rightly afraid to use his power – a power he must consciously choose to exercise – because of the very real moral dilemma that their use creates. How do you live with the ability to give life, knowing that you must take life from someone or something else in order to do so? How do you shoulder a responsibility like that? Seen in that light, Ben’s all-around reticence makes a bit more sense, and his conspicuous refusal to exercise his abilities says something positive (I think) about WHO he is. This scene also raises the spectre of a place that I’m immediately eager to see. Just before she dies, Donovan whispers the word “Babylon” to Ben, and at the episode’s end we watch as Samson tells Jonesy that Babylon is where they’re headed next. The look of horror on Jonesy’s face tells the audience everything we need to know: something dark is hovering just over the horizon, and this makeshift family is now headed directly for it. I can’t wait to get there.

“I will make the sun go down at noon and darken the earth in broad daylight.” – Amos 8:9

Lodz: “Telling you everything now would spoil the adventure.”

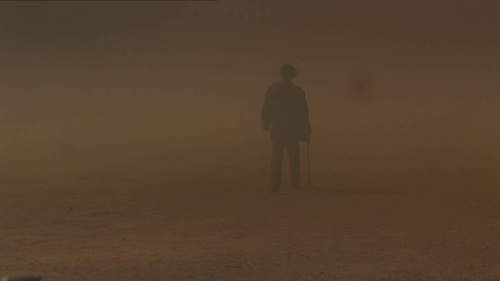

It took longer than it arguably should have, but Black Blizzard finally brings some much-needed color to some of the denizens of the titular Carnivale after two episodes in which these people and their lives remained almost stubbornly ill-defined. The imposition of an outside obstacle that the characters must all deal with in their own ways (a nicely-realized near-apocalyptic dust storm mixing what looks like CGI and practical, in-camera effects) allows us to see these characters in greater relief, allows us to begin to understand WHO these characters are – not as scenery or as archetypes but as human beings. We need that if we’re going to sign up with Carnivale for the long haul, because the show is clearly uninterested in moving its mythology or its larger plot forward at anything other than a snails’ pace (this is not at all a bad thing as far as I’m concerned, but I can see why it was a real problem for some).

As for instance: we knew that Samson was the diminutive, crafty “leader” of the carnival, but what have we actually learned about who Samson IS over the past three episodes? I’d argue that we’ve barely learned anything. The same goes for characters like Jonesy and Lodz and most especially Sofie – all of these characters became significantly more interesting to me as a direct result of learning something about what they seem to want or need during the course of this episode. Black Blizzard got me to care about some of these characters on an emotional level and that raises my hopes significantly for the show as a whole. I’d begun to worry that Carnivale would be an interesting intellectual exercise, but that it would remain emotionally-remote and less-than-galvanizing. Speaking of which…

Carnivale has a strange habit of setting good chunks of episodes during mealtime, a decision that makes sense from a budgetary perspective but that in my humble opinion doesn’t do the show any favors. Carnivale is already a slow, deliberately-paced thing. Having everyone sit down and stop what little motion they were engaged in, whatever interesting carnie-related shenanigans they’d have been mixed up in, seems like a misstep. And it’s a location the show returns to often enough that further drag starts to set in. When I saw that we were returning yet again to this setting I admittedly got a little frustrated. This time period is fascinating. This carnival is a great dramatic location, rife with possibility. These characters are promising. So now let’s DO something with them. Please. Having the carnies talk about where the plot is taking us, as they do here, doesn’t count. Yet almost as soon as the thought crossed my mind it vanished again, because Black Blizzard spends much of its time addressing its characters.

Namely, it forces these characters into cramped quarters and makes them talk to each other – mostly not about Signs and Portents, or Mysterious Baggage Cars, or Gentleman Geeks, but about each other. About themselves. The dust storm that pours through this episode clouds vision almost completely, but in doing so it gives us emotional clarity in terms of the characters. For instance:

Samson, the pugnacious proprietor of the carnival, is herein revealed to be both a vulnerable, sensitive soul and a manipulative @$$hole, all at once. Spending time with him as he plays first the sweetheart with his ladyfriend, then turns on a dime and becomes the vindictive, jealous lover when it becomes clear that he’s not the only one she beds for money is a rewarding experience in part because of how good Michael Anderson is here and in part because it gives us a real look into what makes Samson tick, confirms to us that he’s all-too-human (at least in terms of his emotions). I understood Samson’s vicious hurtfulness, even if I also found myself disgusted by it. That sort of complicated response is what I want from this television show.

Jonesy, previously seen as a roughhewn roustie loyal to Samson and with a bit of a soft spot for kids, is herein revealed to be a more complicated sort of fella – chafing at the chain of command in front of his subordinates and at Samson’s willingness to put the orders of Management ahead of the carnival’s monetary well-being. In a moment that’s fairly reminiscent of the Locke/Ben relationship from Lost, Jonesy secretly sneaks off to confront Management in Management’s trailer only to find that the trailer is empty, that there is no Great and Powerful Oz behind the curtain (or so it seems). At the episode’s end it’s clear that something has shifted in Jonesy and Samson’s relationship, even if Samson isn’t clear on what that something is, or why it’s shifted. I’m very much looking forward to seeing how this develops.

Sofie also gets some time to shine here, taking on an entirely new identity and using it to playact a life that’s not hers. Her scenes with the somewhat-gawky, earthily-charming owner of the local diner are alternately sad and charming. Her converstion with Apollonia at the episode’s beginning haunts the rest of it in retrospect and calls into question Sofie’s mental state as well as her own morality. What she does isn’t harmless, her claims to the contrary, and it’s clear that she let’s things go too far. And yet, her actions here are strangely sympathetic and surely understandable. She’s a young woman yoked to a mother who cannot do anything without her, and who has unfettered access to her daughters thoughts. Who wouldn’t want to escape into a fantasy in that situation? And is it happy coincidence that Sofie’s face is framed to resemble her mother when we first see her after she beds the townie?:

And then there’s Maude Lodz. I’m a relative newcomer to the show who knows little about the fanbase for Carnivale, but I’m going to guess that Lodz is a big fan-favorite. He reveals himself here to be one intriguingly-mysterious blind dude above and beyond whatever mystical hoohah enables him to read dreams and operate generally like he’s got 20/20 vision (While they’re chilling in their shack during this episode Lodz mentions that he gave up his eyes for a fraction of the power at Ben’s disposal – so how is it that he’s able to “see” so well? When he says that he “gave up” his eyes does it mean that he lost his sight? Or does it mean that he “gave them up” in the sense of offering their use to someone/something else? Does Lodz share the use of his peepers with another entity like, say, Management? Am I over-thinking things again? Magic 8-ball says: “Signs point to yes”). Adding to Lodz’ cache: it’s entirely unclear whether the cat is Good or Evil, but he’s pretty darn sinister no matter how you slice it. That’s an alluring mix of traits and the actor Patrick Bauchau sells that mix to us wonderfully well, evoking a kind of avuncular menace in his interactions with Ben. I get the sense that Lodz is covetous of Ben’s power, and that the “test” he gives Ben in Black Blizzard is the first step toward trying to seize Ben’s power from him in some form of “Assumption”.

And speaking of Ben’s power….up until now I’d assumed that the full extent of Ben’s abilities amounted to the healing or resurrection of other people. That’s clearly not the case anymore, and the shift in our understanding of Ben’s power significantly changes the stakes here. Hawkins displays the power to stop and start a massive dust storm. Suddenly, the potential importance of a “war” between Light and Darkness makes a little more sense to me. The victor may be able to shape the world to their liking, and unlike Ben’s healing abilities there do not appear to be attendant consequences to his use of these expanded abilities. We discover also that Ben is weirdly invulnerable. Questions that I hadn’t even bothered to ask (why didn’t Ben die of dust pneumonia the way that his mother did?) suddenly have thought-out answers.

“If anyone causes one of these little ones—those who believe in me—to stumble, it would be better for them to have a large millstone hung around their neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea. Matthew 18:6-7

Clancy Brown’s work continues to impress. Knauf and his writers have given him a heck of a role and he seems to know it. Being most familiar with Brown’s unimpeachable roster of badasses and bastards (often badass bastards) I’m enjoying watching as he employs a whole other set of acting muscles to powerful effect.

As for Brother Justin: he suffers serious defeat in this episode, and it’s tragic to behold even if I think that there should be a permanent moratorium on actors looking to the sky, sinking to their knees and shouting “NOOOOOOO!” One of the maybe-intentional, maybe-unintentional details I most enjoyed about this episode comes when Brother Justin quotes the Bible passage above in a fit of rage and sadness. If you weren’t familiar with Matthew 18:6-7 it would be very easy to assume that Justin had just made an enormous Freudian slip in referring to himself as God. I like that the quote chosen in this moment leaves it up to us, the viewers, to decide whether or not Justin is merely quoting the Word of God, or placing himself in the position of God.

Let’s talk a little more about thorny morality/a potential absence of morality here. Brother Justin’s choice in this episode is clear: return to his duties as Pastor of the Mintern First Methodist church, or remain with the migrants and be “disciplined…and reassigned.” On the surface this seems like a black and white choice. On the one hand you have the Mintern congregation which, so far as we’ve seen, is made up of priggish bigots who are closeted pedophiles. On the other, you have the destitute migrants of the new “temple”; men and women who can indeed be seen to some extent in the same light as the tribes of Israel. The choice, Biblically/ethically/morally/yadda-yaddaly-speaking seems clear. Brother Justin Crowe must stand with the migrants. It is the “right” thing to do. We have seen the Mintern congregation represented by a monster. We have seen the migrants represented by flawed, real human beings. The show itself has led us to feel this way. It wants us to want Justin to foresake the Church body and do what we’re always told true servants of God should do: feed and clothe and care for the sick, the lame, the poor. Tend to their physical and their spiritual needs.

But that’s not quite right, really. Not if we’re going where Carnivale seems to be heading. If things continue the way that they are now then Justin Crowe isn’t going to stay a nice man for very long. And that being the case, then choosing to stay with the migrants may be considered the “wrong” choice here. And if it’s the “wrong” choice then either returning to his Mintern congregation is the right choice, or both are “wrong choices”. That’s a hell of a thing.

Justin’s attention to the needs of migrant children, his grief over their passing, suggests that he and Iris probably had a rough childhood. I’m starting to wonder if Justin didn’t become a preacher out of a desire to atone for some past sin, if that sin might be rooted somewhere in that childhood. Related to this: I’ve been wondering how and why Brother Justin will end up crossing over to the Dark Side (assuming that he will), and in Black Blizzard we may have gotten (part of) the answer. There’s a sense of intense fatalism mixed with limited free will in this show so far – a sense that a series of tumblers are (slooooowly) falling into place; a sense that Justin and Ben can struggle against their destinies but only with great difficulty, and with no guarantee of success. The dead bodies of the migrant children and the destruction of “Dignity” in the form of the Dignity Ministry may signal the moment when a man trying his hardest to be Good begins to question just what the point of being Good is, anyway? Everything Justin has achieved so far, despite what seem like the noblest of intentions, has been through force, through fear, through manipulation (the migrant woman sees the light after Justin scares the coins out of her, Carol Templeton gives up Mr. Chin’s when Justin blackmails/just plain spooks him, Carol’s cousin and his threats seem to vanish when Justin appears to strike him with some kind of attack). Might the dead children in some sense represent the death of the “faith like a child” that Justin seems to hold? The rejection of New Testament forgiveness in favor of the Old Testament wrath that has been a far more successful tool for him? In favor of something darker still?

I have no idea. But I like that I’m thinking about this stuff, and I like that the show allows this kind of thinking without it seeming ridonkulous. The best television entertains us, moves us, while also engaging our minds. With Black Blizzard, Carnivale managed the feat of engaging my mind and moving my emotions. That bodes well for future episodes.

The episode ends with Justin brought low by grief and with the carnival still on its way to Babylon, the last-known location of Henry Scudder, a place with a wicked reputation – depending on who you ask, a group of 3 or 4 rousties and/or freaks were hung there – and the title of next week’s episode. As previously mentioned the town’s name contains some seriously-heavy Biblical significance. I’m told that I’m going to love Babylon, and I’m looking forward to writing about it. If you vote to Renew Carnivale, I’ll give my thoughts on the episode next Friday right here on Chud.com. So get going and vote “Renew” or “Cancel” in the comments below, or on Chud’s super-swanky, refurbished message boards. Enjoy your weekend, and be good to one another.

All screencaps courtesy of fishstick theatre.