This week, two events occurred that got me pondering about my favorite genre of fiction, horror. First, James Rolfe over at Cinemassacre posted a video where he and Mike Matei debated whether certain films should be classified as horror or not. Secondly, in the week leading up to Crimson Peak, there seems to be a media blitz happening in regards to distancing the film from the horror genre. Multiple reviews and videos have popped up that seem to be encouraged to call the film anything but a horror movie. Guillermo del Toro himself tweeted that he doesn’t consider Crimson Peak a horror movie but rather a Gothic romance. Our own Travis Newton compiled this marketing switcharoo right here.

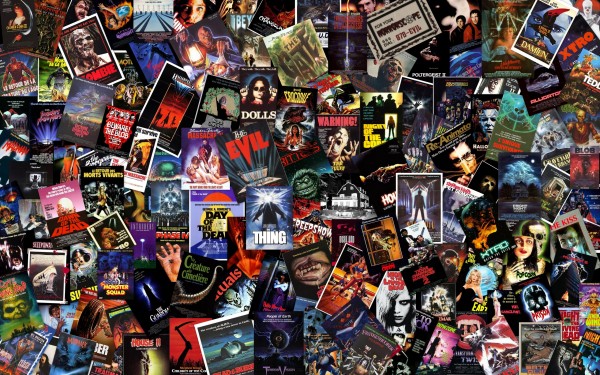

Throughout all of film history, “horror” has often been considered something of a derogatory term. Horror films often summon up specific images in a viewer’s mind or even suggest a certain kind of tone. There’s also a cheapness associated with the genre thanks to the majority of horror films being lower budget affairs. All these preconceived notions and multiple influences stir together into what the general public considers a horror film. But, in truth, there really is no such thing as a horror movie. In fact, Stephen King himself has been quoted as saying that there really isn’t a horror genre, but rather that most horror stories could fall under the banner of dark fantasy.

Horror isn’t so much a genre as it is a supposed intention, but that doesn’t really pan out. While we ascribe certain tropes to horror (if zombies, vampires, werewolves, or serial killers are in it, it must be horror!), the presence of those tropes don’t necessitate the intention of creating fear. Look at films like Fido, What We Do in the Shadows, or Serial Mom for such examples. But, if horror is an intention, then could such films like Schindler’s List, A Clockwork Orange, and American History X be considered horror films?

There are often attempts made to class up some films that might be called “horror” by sorting them under the moniker of “suspense thriller” or other such titles. This has always been the biggest indicator to me of how most people separate “horror” from other genres. It allows the viewer a perceived notion of betterness. “Oh, I don’t watch horror movies, but my favorite films are Seven, Psycho, and The Silence of the Lambs.” If something tries to pass itself off as a psychological thriller or a suspense film, I’m calling it a horror film.

I’ve always taken a much more inclusive view of the horror genre, recommending such films as The Night of the Hunter or The Manchurian Candidate with the addendum that, “I think it’s a horror movie.” I’d like to broaden my viewpoint to an exaggerated level: Everything is horror.

If horror doesn’t truly exist as a genre, then there are no “horror” movies. Therefore, anything could conceivably be a horror movie. The nightmarish visages of the Wayans brothers in White Chicks are much more horrifying than any Wishmaster film. The appalling antics of Jack and Jill fill me with more dread than Wrong Turn 2. And Requiem for a Dream terrified me beyond comprehension, something that Halloween 5 could never claim.

I love horror films, and that’s why I’m never afraid to find the horror film lurking within any romantic comedy or period drama. Instead of segregating these stories away from the “respectable” genres, we should embrace the fact that anything has the potential to be horror to the right viewer. So while Guillermo del Toro and the marketing machine over at Universal/Legendary are scrambling to entice audience members who wouldn’t be caught dead seeing a horror movie (or trying to appeal to award ceremonies who would never nominate a horror movie), I’ll be walking into this Gothic romance with the expectation that I’ll be seeing yet another entry in my favorite genre.

If you like how stupid I am, follow me on Twitter and listen to my podcast.