Silver Surfer #1 (Marvel, $3.99

By Adam Prosser

Comics fans talk a lot about the difference between modern and classic comics, but the discussion is often more on the content or the superficial writing and art styles. What I don’t see acknowledged as much is just how radically different the basic narrative rhythms and structure of comics were back in the Golden and Silver ages. Sure, we talk about “compression” and sometimes pause to marvel (or, more often, chuckle) at how drastically old comics can swerve between panels—the way you might get a robot duplicate or an alien invasion thrown into a story at the last moment, usually as a sign the writers were desperate to wrap the thing up within the allotted number of pages—but it runs deeper than that. The very best Silver Age comics have a style to them that’s confident in itself, yet feels utterly unlike modern comics storytelling (or even the kind of comics that came before or after), to the point where the modern reader sometimes finds it off-putting. The key, though, is to understand just how different the intent was. Modern comics are heavily inspired by film and TV, and attempt to emulate their pacing; as we’re constantly exposed to those media, it feels “natural” to us. But older comics didn’t necessarily think of themselves as films trapped on a page. They might be more inspired by books, or static artwork, or collage. The beat poets were a huge influence on pop culture at the time, and definitely inspired the Marvel bullpen as well.

The fact of the matter is, “story” is actually only one of the elements in a comic, and it’s not even necessarily the most important one. That’s so out of line with our current thinking that it feels weird to even type, but it’s true. Those older comics tended to put the emphasis on the art, and even the best writers, like Stan Lee, were often more concerned with things like dialogue and character beats than with the plot of the comic. It’s not hard to see that a lot of those old comics were being made up as they went, with the basic narrative sometimes being simply a hook on which to hang the artwork. Plotting and narrative are the aspects of art that speak most directly to our logical left brains, but the greats of the Silver Age were interested more in addressing their audience’s creative and emotional right brains, through iconography, through subtext, through the sheer power of the artwork and compositions. Just as the “story” isn’t necessarily the most important thing about a rock song, or a poem, or a painting, so it wasn’t necessarily the point of a classic comic.

I hasten to add that Silver Surfer #1, the comic I’m actually reviewing if you can believe it, has a story. It has a good story, even, though like many comics these days it can be a little hard to tell if it will pay off based simply on the first issue. But it’s drawn by a guy, Mike Allred, whose prior work suggests he’s one of those guys who gets the narrative-transcending properties of old comics. That’s not to say he doesn’t know how to convey ideas, character, and action via artwork anymore than it is to say that about the old masters. It just means that he knows that the images on the page mean more than just showing you what’s happening at a given moment.

Writer Dan Slott, meanwhile, is more of a left-brain kinda guy—as writers tend to be—but he, too, seems to have dialed back on his trademark dense plotting, snappy dialogue and clever riffs on Marvel Universe continuity (though all those things are still there) and allowed the comic to exist in this “transcendent” dimension. The story actually follows two parallel narratives, one of them (naturally enough) about the Surfer of the Spaceways being called on to defend a bizarre, hidden tourist planetoid as part of his attempts to make up for his prior collaborations with Galactus. The other involves a girl named Dawn who’s living a completely mundane life on Earth, helping her father manage a bed & breakfast, and whose connection to the other storyline is bafflingly unclear even when they’re forcibly thrown together.

I’m sure Slott, of whom I’m a fan, will turn this into something clever and entertaining. But as I’ve hopefully conveyed by now, the real appeal of this issue isn’t what’s going to happen. It exists, zen-like, as an artifact unto itself, something to look at and marvel at, even beyond Allred’s typically ideosyncratic artwork. I missed his work on the FF books and elsewhere in the Marvel U., but his classic creation Madman has some of the same dreamlike spirit of the old Silver Age comics, and he’s, wonderfully, managed to transfer some of that into the Marvel Universe with Silver Surfer. It’s such a perfect way of tackling a character who’s always been strange, psychedelic, and far removed from reality. We talk a lot about how superhero comics are modern day myths, but myths are rarely about sophisticated narratives; they’re frequently more like ideas than stories. Taking this tack for Silver Surfer helps him reassert his place as perhaps the most mythical superhero of them all.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Sandman Overture #2 (DC Vertigo, $3.99)

Sandman Overture #2 (DC Vertigo, $3.99)

By Cat Taylor

I’m really happy that Neil Gaiman is writing more Sandman stories. Like many people in my age group, his original run of Sandman was my favorite ongoing comic series in the 80s and 90s. There was just so much to like about it. Whether it was because you were a Bauhaus-loving Goth and it appealed to your dark-fiction urges, or whether you were a high-brow mythology and literature lover who enjoyed the inclusion of ancient stories and figures in modern comics, or whether you just love a good fiction/horror story, Gaiman was the comic writer for our generation.

After the knee-jerk elation at reading something like “Gaiman to write new Sandman series,” a bit of hesitation set in and a dark cloud of fear emerged. “What if Gaiman Phantom Menaces all over the new series? Can my heart stand another molestation of my childhood?” While the first issue of the new series was a slow intro, one thing it thankfully did was alleviate any such unnecessary fear. Gaiman’s still got it and he’s keeping the new series fresh, yet in tune with the atmosphere and style of his original series. Of course, there was really never anything to worry about since Gaiman has remained a prolific comic and novel author of many different properties, and even his worst works are better than average.

As revealed in the first issue, Gaiman is picking up the new Sandman series roughly at the point where he last left it. The Sandman/Morpheus/Dream we most remember from the old series is still “dead” and the new guy, “Daniel” is running the dream-world. In issue number two; all the different incarnations, or aspects, of Sandman discover that the death of the “classic” Sandman has created a situation that will cause the destruction of the entire universe. While the various incarnations say that this isn’t their concern, they feel compelled to individually yet simultaneously investigate and correct the problem. The whole scenario here is both simpler and more complicated than I’m making it sound because Gaiman doesn’t shy away from the confusion of multiple incarnations of higher-level beings. To use a movie analogy, Sandman Overture is to Crisis on Infinite Earths, what Primer is to Back to the Future. However, Gaiman takes a few shots at his own pseudo-intellectualism in making this so complicated by letting some of the characters call each other out on their pretentiousness.

While Gaiman’s writing is definitely the star attraction in any of his comics, J.H. Williams III is probably the best possible artist to be handling the new series. It takes a special kind of artist to effectively convey the surrealism and uniqueness of the dream world and Williams nails it. Each page is brilliantly illustrated with beautiful foreground and background details that I could examine with interest for hours even if there wasn’t a word on the page. It’s been a long time since I’ve had that kind of love for a comic book artist. While I’m at it, I also need to give credit to the equal superb colors supplied by Dave Stewart.

If there’s a weakness in the new series so far, it’s that the first two issues feel a bit slow and drug out. It seems like each issue was about five pages longer than necessary and the cynical side in me thinks that DC may be encouraging Gaiman to pad the story so they can sell more trade collections later. Regardless, I have enough faith and confidence in what I’ve read so far and Gaiman has more than proven that he knows what he’s doing over the years.

5 out of 5 stars

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Snowpiercer Volume 1: The Escape (Titan Comics, $19.99)

Snowpiercer Volume 1: The Escape (Titan Comics, $19.99)

by Graig Kent

A few weeks ago the returned-to-form NBC comedy Community presented what is perhaps my favourite episode of the series yet. In “App Development and Condiments”, the ever-susceptible students and faculty of Greendale are introduced to a new peer rankings smartphone app called Meowmeowbeenz, which allows them to rate other people who have joined this not-so-social network on a scale of 1 to 5, with the hitch that the higher one’s been rated, the more weight is applied to their ratings. In typical Greendale fashion, things get crazy out-of-hand and within days a futuristic looking society has evolved on campus,with people grouped by their rank, the 5’s having total sway over the progress of the school, the 1’s considered the dregs, and everyone in between trying to climb over each other to move up.

Through this episode, Community aims its satire gun at the sociological impact of social media and online culture as it bleeds into and becomes inseparable from the real world, all under the guise of well used but rarely spoofed Science Fiction trope of extremely well-defined classes and hierarchical societies. We’ve seen these types of societal layers as recently as The Hunger Games or the forgettable Justin Timberlake vehicle In Time but it’s been a part of science fiction for a very long time.

Case in point, Snowpiercer, a French graphic novel (Le Transperceneige) by Jaques Lob and artist Jean-Marc Rochette, first appearing in serialized form in 1982. Set in a post-apocalyptic world that has literally frozen over, the titular train, the “Snowpiercer” (aka Saint Loco, aka Olga) is a heavy duty, near perpetual-motion machine dragging behind it a thousand cars containing the last of humanity on an endless journey through the white wastes. On this train, a person’s status increases the further towards the engine they get, and naturally the living conditions prove more favorable as well.

The people at the back, the “tail-fuckers” as they’re called, are an almost unknown commodity to those further up the train. As the world was falling apart (an indeterminate time ago, years at least), they were the last to clamor onto the train, fighting for space and food and utter survival aboard unheated cargo cars. One man Proloff, escapes the tail, finding himself forward on the train, in a place where he shouldn’t be. The military, who call home squarely in the middle of the train, seize him and pair him with a “level 3” sympathizer, a woman from a group of advocates for the lower compartments.

They’re shaved down and quarantined before eventually taking a journey up the train, exposing Proloff to a life he hasn’t seen since the clamoring that brought him aboard, and some things, like Mama (a vat of living, regenerative tissue that supplies most of the train its meat) he’s never seen. Through this sojourn up the train, Lob exposes the reader to the structure of life on the train (including religion, drugs and sex), as well as slowly exposing its origins in nebulous ways.

Titan Comics presents, for the first time in North America, Lob and Rochette’s story in an English adaptation, largely in anticipation of the domestic release of Joon-Ho Bong’s adaptation. The advance hype for the book often list it as a “classic” of French comics, but it’s unfortunately an oversell.

The main problem with Snowpiercer, at the very least in this form, is its packaging. Since it was originally presented in serialized form, it doesn’t read as well when presented as a whole. Each segment is, to one extent or another, compartmentalized, but in the formatting of this collection it all runs together without transition or any indication of chapter breaks. There are a half dozen recaps of the book’s main premise which seem extremely repetitive when reading in a single sitting.

Beyond that, there isn’t altogether much of a narrative to Snowpiercer. The story is an exploratory one, not really contingent on its characters at all. Proloff is the eyes through which we’re presented this world, but the guards escorting him up the train and his advocate/lover might as well be talking directly to the reader for all the presence he actually has. If there’s any sort of social critique (anti-Nukes perhaps or an examination of elite conservatism and class bias?) it’s kind of lost to the era of its production.

As it stands it’s an intriguing look at a highly implausible, some might say doomed society moving onward with no direction and very little hope for the future. Or perhaps that’s the critique, that if we as a society can’t see fit to help elevate the less fortunate and equalize ourselves into a societal balance that we’re inevitably doomed.

Is there good? As an exploration of a distinct future/post-apocalyptic society, yeah it’s quite satisfying for fans of that sort of thing, with intriguing ideas that, while not unique to this story, combine to form an interesting whole. Rochette’s art is great, in stark black and white it has the feeling of a newspaper strip, with panel composition taking more priority than page layouts. The details laden in the book, from character design and clothing to the differences in train car interiors, really build the world. He captures the claustrophobia, such that any amount of space feels vast in comparison. It’s truly Rochette’s show more than Lob’s tell that lifts Snowpiercer out of forgettable territory.

There’s a second collection now available from Titan (written by Benjamin Legrand after Lob’s passing in 1990) which opens up the world, and that sort of broader exploration of the train, the world outside, and the (possible) conspiracy that brought humanity to this point seems to be what this first volume was leading into. In many ways this first volume seems like a prologue, an introduction to something bigger, more revealing. It certainly doesn’t feel like Proloff is a main character, rather that it’s the environment that is the show. (I will review Volume 2 in a forthcoming column). I’m curious to see Bong’s interpretation of this world, as this story doesn’t demand it be a direct adaptation, and he could really tell his own story with it.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Amazing X-Men #5 ($3.99, Marvel)

by D.S. Randlett (@dsrandlett)

Let’s get this out of the way: I love Nightcrawler more than is rational. I’d even go so far as to say that he’s my second favorite superhero despite the fact that he’s something of an also-ran in the “best mutant” sweepstakes. He’s always played a second fiddle role on the X-Men (although there was that time he saved the day by teleporting behind Magneto to bust his head with a lead pipe, serving alternately as a straight man sounding board for Wolverine and the team’s wisecracker. But there’s always been something more there, and before they killed him off in 2010’s Second Coming storyline, Marvel seemed to sense this. There had been several attempts to get the character his own ongoing, or to push him to the forefront of the team. In the case of the latter, this only really worked in Excalibur (still one of the very best versions of the character), but in the case of the former creators often struggled with finding an angle into the character. In a lot of ways, Nightcrawler became something of a symbol of unfulfilled potential, and what better way to make good on the character than a dramatic death? Instead of putting a stamp on the character and closing the book on him, the death of Nightcrawler only accentuated the fact that there was still something for the character to say, and we’ve been waiting decades for him to say it.

Unfulfilled potential is a good descriptor for Jason Aaron and Ed McGuinness’s Amazing X-Men, a series that bears all of the hallmarks of the worst impulses of latter day Marvel comics. Where DC at its worst can steer its characters into a useless and sham seriousness, Marvel can go toward the other extreme, chasing a sense of fun while providing no real sense of character or content. Many of the big emotional beats in these first five issues fall completely flat without a sense of buildup or payoff. The reunion of Wolverine and Nightcrawler is a completely wasted moment, and the “hero shots” are without any real heft. Aaron’s script in this run is, much to my chagrin, completely rote. And look, bringing characters back from the dead is hard (and often pointless), but such stories do provide opportunities to focus on what these characters represent. Aaron focuses on the least interesting stuff about Nightcrawler and pays the most interesting stuff the barest possible lip service. One of the best things about Nightcrawler is that he’s a bundle of paradoxes: a religious demon, a man who is able to find happiness despite intense oppression. In Aaron’s script, Nightcrawler is a guy who likes pirates. There is some stuff in these first five issues that does work. Storm is great, for one, and the ending of this story does open up some interesting threads for my favorite mutant, but very little stands on its own.

The mostly empty script is a real shame, as Ed McGuinness turns in some absolutely great work here. His depiction of Nightcrawler, getting back to Dave Cockrum’s classic costume design, is fantastic and the aesthetic of the series grows out of that. This is easily some of the best work of his career, and he manages to imbue the narratively inert “hero shots” with some great aesthetic weight. McGuinness also puts a lot of thought into Nightcrawler’s fights with Azazel, giving their encounters (which are uninhibited by space as they bamf around) an appealingl sense of choreography. The art also has a lot of character that’s missing from the script, and if there were more weight here narratively, McGuinness could bring out the pathos of these characters along with the high adventure.

Amazing X-Men is not terrible, but not particularly good. I hope that Aaron’s departure and the arrival of Chris Yost and Craig Kyle as the writing team brings this book the narrative voice that it so sorely needs. They’ve got a great artist, and some great characters to work with. Let’s hope that the series, like a certain blue elf, comes to life.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Nemo: Roses of Berlin HC (Top Shelf, $14.95)

Nemo: Roses of Berlin HC (Top Shelf, $14.95)

By Adam X. Smith

While getting ready to write this review I got drawn into a conversation with a former CHUD writer about Ridley Scott’s recent turkey The Counsellor in which said writer compared the script’s palpable misogyny to the work of Alan Moore and Frank Miller, saying they found Moore’s work “to be as misogynist and troubling as Miller’s — he just hides it better, and under a more elite veneer”. While not specifying the nature of this veneer, it revolved mostly around the portrayal of women in Watchmen and Lost Girls, as well as Mina Murray in League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. I’m not trying to dismantle their argument – they’re entitled to their opinion, even if I disagree – but that was essentially the meat of it.

Now I will admit that I have a glaring bias here, and that I may not always express myself to the best of my abilities, but I will reiterate now the point that I made then, which is that I don’t consider Moore’s supposed misogyny to be even a shadow of that dripping from the work of Miller, whose entire back catalogue only seems to deal in four preset female personality types: spunky teenagers, imperilled ingénues, evil sex goddesses and less-evil-but-still-morally-questionable sex goddesses. I could be wrong, I could be right. All I can say is that Moore at least bothers to try to be representative of women as something other than sex objects, even if they aren’t the ones people pay attention to when they read his books.

To wit, Janni Dakar aka Captain Nemo II, who has gone from being a secondary character in the first part of LXG: Century (moonlighting as Pirate Jenny from The Threepenny Opera) to getting her own trilogy of graphic novels. Last year we had Heart of Ice, in which a still young and inexperienced Janni battled Lovecraftian horrors and rival adventurers on a quest to reach the South Pole. This year, we get Roses of Berlin, in which Janni and Broad Arrow Jack must rescue their daughter and son-in-law from the clutches of Adenoid Hynkel, dictator of Germany-Tomania, and battle through sleepwalking stormtroopers and Carl Rotwang’s gynoid Maria to the centre of the Berlin Metropolis.

Those familiar with the LXG franchise will be pleased to hear that the crossover elements continue to come thick and fast, with appearances from the aforementioned Great Dictator, Doctors Mabuse and Caligari and the clearest look so far at Moore and Kevin O’Neill’s reimagining of WWII-era Germany (think Fritz Lang’s Metropolis but with swastikas double-crosses), as well as the return of Janni’s nemesis, the immortal African queen Ayesha. Like the individual episodes of Century and Heart of Ice before it the book acts as a discrete done-in-one story set in a specific time and place in the canon, attesting to the ease with which Moore’s plotting fits into long established backstory Easter eggs from earlier in the series whilst retiring the largely episodic nature of the first two volumes in favour of yomping around a particular environment and era (rendered superbly by O’Neill and colourist Ben Dimagmaliw) for 56 pages, which might seem a bit dodgy in terms of pacing but in actuality gives Janni’s rescue mission an appropriate sense of urgency and purpose – rather than simply jumping from pirating it up in New York to deciding to boom straight for the South Pole as in Heart of Ice, the timeframe and motivation of her rush to Berlin makes a lot more narrative sense.

But yes, I know the elephant is still in the room, so returning to my earlier point: is this story, or the characters in it, inherently misogynistic? Well, that’s a tricky one to be certain, and thinking about it only makes it tougher for me to call. Ayesha and Maria are hardly high benchmarks for female representation, but in their cases I’m liable to blame the source material – Ayesha sharing a creator with Allan Quartermain is hardly an excuse for her being a bitchy ice queen, but it certainly makes logical sense. Also, they’re villains – you’re supposed to hate them. However, in being such a despicable character, Ayesha is all the more a dark mirror of Janni Nemo: despite being from Africa, Ayesha is pale white, while Janni is portrayed, like her father, as being of Indian Sikh lineage; Ayesha is eternally young (spoilers) [but not immortal], while Janni is approaching middle-age but still is more than a match for most everyone she encounters; Ayesha maintains her foothold in Western society by associating herself with powerful men willing to do her bidding (Hynkel, Charles Foster Kane), while Janni as captain of the Nautilus is essentially Queen of the Pirates, feared and respected by her crew and many enemies in spite of being a woman of colour in an age of fascism.

Fundamentally, though, what sets Janni and Hira Nemo apart as female characters is that they are resourceful, tenacious, are under-estimated by their opponents every step of the way, and in spite of there being a scene in a state brothel (this is LXG after all – there is a certain expectation of low-grade smut), neither of the Nemo women have to get their tits out or otherwise debase themselves in service of their goals.

So we return once again to the question: Does this sound like the work of someone who fundamentally hates women? I don’t believe it is. I think that when it comes down to it, you cannot portray a character complexly and with integrity if you cannot empathise with them in some manner. It’s the old “no villain ever believes they’re the villain” chestnut writ large, and even though Alan Moore’s work is at bottom a highly stylised and well-produced piece of fan-fiction with all the baggage that entails, it’s the very fact that he considers himself a fan of these characters and their progenitors that makes me consider accusing Moore of misogyny to be reductive and missing the point – you might just as well accuse The Cement Garden or Lolita or Fight Club of advocating incest or paedophilia or soap-based terrorism.

I am Raggedy Adams. I need no sympathy.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

All-New Ghost Rider #1 (Marvel, $3.99)

By Jeb D.

If there’s one pleasure that corporate superhero comics can still provide today, it’s watching the emergence of amazing new artistic talent. That’s not to say that writers can’t make their own mark, but the demands of trademark protection and intellectual property exploitation have the tendency to circumscribe even the best efforts of writers like Jason Aaron or Greg Pak; at their best, they generally provide satisfying variations on established continuity. On the other hand, if an artist can just make sure that the costumes are recognizable, they frequently have the opportunity to expand on their storytelling tools in ways that most writers don’t. Artist Tradd Moore’s work on the Luther Strode series has had him flying somewhat under the radar over the past couple of years, and he’s contributed to Ales Kot’s Zero, but this new Ghost Rider series looks like the breakout of a major talent.

Structurally, this is about as “New” a Ghost Rider as you could ask for: in Felipe Smith’s script, not only do we have a non-white protagonist taking on the flaming mantle, but he’s not even riding a motorcycle. Our new spectral-rider-to-be is Robbie Reyes, a Latino teenager from East L.A., whose job at an auto shop helps to support his disabled younger brother Gabe. When thugs steal his brother’s wheelchair, and rough Robbie up in the process, he decides to enter an illegal road race for the prize money that will allow him to take his brother and escape the deadly life of the ghetto. Of course, he has to “borrow” a car from work without telling anyone–a black ’69 Dodge Charger–but that turns out to be the least of the risks he’s taking, on this issue’s way to a stunning, violent conclusion, and lead-in to Robbie’s discovery of his new identity.

It would be hard to think of a more hackneyed comic-book setting than the urban “mean streets,” where our hero usually faces the first of his challenges, but Moore’s eye for imaginative detail brings a kind of exaggerated realism: the environment becomes a striking visual treat, feeling lived-in but with just the right tinge of colorful fantasy for a comic-book hero, while all the characters are well-defined; larger than life and “cartoonish” in the best sense of the term. Huge kudos to colorists Nelson Daniel and Val Staples: even the earth-tones in this book just pop off the page; and Moore and his colorists combine to bring unusually distinctive life to the largely non-white cast, with a fluidity that reminds me a bit of Kyle Baker. And given that our new Ghost Rider will evidently replace motorcycle mayhem with muscle-car madness, Moore appears to be having the time of his life with the racing scenes: tires screech and smoke, there are perfect cuts from the speedometer to Robbie’s hand on the shift, foot on the pedals, and a classical hero’s determination in his eyes. As the race flies by, Moore drops in some foreshadowing that you’d probably need a second viewing to catch, so perfectly does he move your eye along, racing across panels and through the gutters.

And if Moore’s the largest part of the artistic package, it’s clear that this is a well-thought-out team effort: Manny Mederos provides some nice video-game style graphic design on the credits page, and Smith himself contributed one of the variant covers.

I’ve never worked up much interest in Ghost Rider as a character, and I really figured that Aaron’s recent psychotic run on the book was as much singed-skull action as I’d need for the foreseeable future. But even if I’m not wholly convinced that making the rider a Hispanic muscle-car racer is enough of a conceptual rebirth to invest me in the character, I’m absolutely onboard for the first arc, just to see what other eyefucks Moore, Daniel, Staples, and Smith have in store for me.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

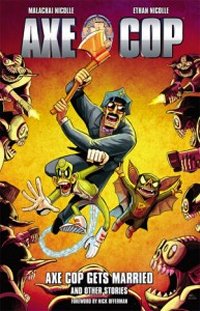

Axe Cop TPB vol. 5 (Dark Horse, $14.99)

By Cat Taylor

Although I assume most people who read this column are already familiar with the concept of Axe Cop, there may be a few readers who need to come up to speed. So, for the benefit of the minority, Axe Cop originated as a web comic where the talented adult artist, Ethan Nicolle, took the stories and playtime imaginings of his five-year old brother Malachai, and drew them in comic book form. Ethan made practically no attempt to make logical sense of the stories and drew them as close to what his little brother was telling him as possible. The results have been absurdly hilarious. Since that time there have been several trade collections of the work and even an equally hilarious Axe Cop cartoon series. I am a huge fan of the comic and cartoon and I think the concept is brilliant.

As you may imagine, the concept in its purest form has a limited shelf life because children grow up fast and almost five years later, there is a big difference in the imagination and world perception of a nine-year old as opposed to a five or six-year old. In this trade collection, you can mainly see a change in the level of unintentional hilarity and absurdity in the book’s main story, “Axe Cop Gets Married.” It’s a longer story that actually has some sense of a narrative flow. While much of the story is still pretty funny due to the still childish imagination on display, the more solid structure and longer narrative proves to be a weakness for Axe Cop.

The strongest works in this collection are the shorter stories that appear to come from Malachai’s mind when he was possibly a year or younger. One of these stories puts Axe Cop in the background because he’s taking his Birthday month off to sleep and eat cake for the entire month. As a result, a pack of dogs get superpowers and fight crime in his place. However, the funniest bits of all are the one and two page comics that answer questions from readers such as “Is there anything that Axe Cop is afraid of?” Apparently, Ethan reads these questions to Malachai and then draws Malachai’s answers in comic form as Axe Cop story shorts. One theme that recurs frequently in both the reader questions and more “proper” comic stories is characters killing themselves or each other so they can resurrect themselves in more powerful mummy form. How they are able to turn themselves into mummies after they’re dead is never explained but that’s the kind of absurdity that makes Axe Cop so great.

Something that occurred to me while reading this trade was just how wonderfully synchronous all of the events have fallen into place to allow Axe Cop to come into existence. It’s a series of events that could almost never occur in any other parallel universe. Consider that first you had to have two brothers who were over 20 years apart in age yet who are still close. The younger brother had to have a vivid imagination and be more into superheroes and monsters than sports. The older brother had to be a talented comic artist with a strong sense of cartoon character design, narrative illustration, a unique style, and the ability to artistically convey the humor he saw in his younger brother’s stories. Finally, the older brother had to have the intelligence and imagination to realize that drawing his little brother’s stories as comics would be hilarious and worth doing. Plus, he had to have way to widely distribute the results. If you ask me, the fact Axe Cop exists is just short of a miracle. If this is last we get of Axe Cop due to Malachai growing up, then I say we were lucky to have ever had it in the first place and I’ll just look forward to more cartoon adaptations. However, there is hope for an extension of life. As you would discover by reading the notes about how the story of “Axe Cop Gets Married” came to be, Ethan married a woman who has two children who are younger than Malachai was when he first dreamed up Axe Cop. Now, Ethan and Malachai play Axe Cop with the step-kids. So, there are two new young and naïve minds that may be able to drag this concept out for a few more years and hopefully keep it fresh. If not, putting Axe Cop on extended life support will likely become sad. If this is the first you’ve heard of Axe Cop, you’ve really been missing out. Look up the older comics and watch the cartoons. If those don’t make you laugh then I don’t understand your sense of humor.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars