One of the most hideous innovations of the second World War was the imprecise, expensive, and utterly terrifying use of air raid bombardment on an unprecedented scale. It’s no mystery then why Death himself –the narrator of both the novel and film The Book Thief– soars through the clouds, looking down at the world below. (Only Roger Allam could provide said narration with such mercilessness and warmth at the same time.) It is he who guides us into the story of Liesel Meminger, a girl of 12 or 13 who by both black train and black car travels through the snow-white countryside to be delivered to her new foster home. This is only one of many foreboding images that coat Brian Percival’s melodrama of the impact World War II had on lower-class German villagers, as well as the Jews and Communists that suffered more stark fates. The story weaves through several years, time marked by the length of Liesel’s golden hair and the volume of words she’s inscribed on the basement walls in chalk as she learns to read.

One of the most hideous innovations of the second World War was the imprecise, expensive, and utterly terrifying use of air raid bombardment on an unprecedented scale. It’s no mystery then why Death himself –the narrator of both the novel and film The Book Thief– soars through the clouds, looking down at the world below. (Only Roger Allam could provide said narration with such mercilessness and warmth at the same time.) It is he who guides us into the story of Liesel Meminger, a girl of 12 or 13 who by both black train and black car travels through the snow-white countryside to be delivered to her new foster home. This is only one of many foreboding images that coat Brian Percival’s melodrama of the impact World War II had on lower-class German villagers, as well as the Jews and Communists that suffered more stark fates. The story weaves through several years, time marked by the length of Liesel’s golden hair and the volume of words she’s inscribed on the basement walls in chalk as she learns to read.

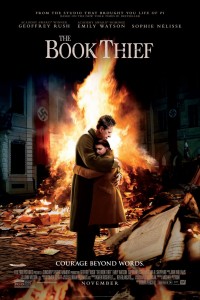

Liesel is delivered to the Hubermann household at the film’s start, and a multi-dimensional and beautiful dynamic is quickly developed between the girl and her new parents, Hans (Geoffrey Rush) and Rosa (Emily Watson). Sophie Nélisse is nothing short of a revelation as Liesel, playing against adults and children with equal grace. All eyes and curls, Nélisse subtly navigates the years and the heartbreaks and the small joys of this story, never failing to provide the film a warm, beating heart. But firmly couched in the traditional language of the prestige historical drama, The Book Thief struggles to contain the scope of the story and maintain each of the important relationships in Liesel’s life. The story derives its main tension from the appearance of Max, a young local Jew played by Ben Schnetzer, at the family’s doorstep. Obligated by both a debt to the young man’s father and a profound sense of decency, Hans leads the family in sheltering him through extreme sickness and risky Nazi inspections.

The relationship that forms between Liesel and Max would seem to be the core of the film, and yet it is never allowed to truly flourish as strongly as, say, her relationship with Hans, or even Rudy- a chipper village boy infatuated with her. The film dutifully explores the two bonding over their hatred of Hitler and love of books, but a relationship that should be utterly life-altering for Liesel is thinly sketched relative to others in the film. It’s by no means skipped over, but the brief poetic exchanges seem  insubstantial when this attractive, intellectual man is supposedly in their basement for months or years during a formative time in this girl’s life. There’s an entire movie there, and yet it is only the third or fourth most meaningful relationship in this film, and it restricts Schnetzer’s fine performance from becoming dimensional to any degree.

insubstantial when this attractive, intellectual man is supposedly in their basement for months or years during a formative time in this girl’s life. There’s an entire movie there, and yet it is only the third or fourth most meaningful relationship in this film, and it restricts Schnetzer’s fine performance from becoming dimensional to any degree.

Instead we experience the grand Holocaust drama filled with the majestic John Williams compositions that take us through the years. Brian Percival –frequently found behind the camera for episodes of Downton Abbey— consistently crafts effective scenes around compelling moments, but there is the feel of a highlight reel that is often the compromise of such adaptations. In fact, as vulgar as the comparison may be, The Book Thief ends up feeling remarkably like Harry Potter And The Very Important WWII Drama, as the adaptive structure is so similar. The collected scenes are too episodic to dig particularly deep into any particular emotion or bit of character growth, while the anecdotes are too constrained by the narrative structure of the film to create a proper sense of passing time. You’d be forgiven for thinking the film takes places over just a few weeks, were it not for some dialogue and Liesel’s lengthening hair.

As the film approaches its climax, there is a sequence that has Liesel expressing herself through prose I must assume originates from the book. For a brief instant the film opens up and descriptions of Emily Watson’s character as “clad in thunder” and Rush’s as sporting an “accordion for a heart,” make it clear why the book has been so well-lauded. Alas, it also illustrates why this is a novel that may have been better left as such, as its most powerful moments are, by their very nature, fixed on the page. No book is unadaptable, but some require more radical reshaping or deeper digging than others to transcend adaptation and become something singular. In fact, there are a few sequences in the film –particularly its last and, admittedly, most touching major scene– that achieve that sort of uniquely cinematic impact- enough that one wishes for more. Overall the film tugs the right heart strings and juxtaposes humanity and evil as expected from a rich war drama, and the many beautiful moments and performances it captures should not be ignored. That said, I suspect The Book Thief may end up serving mostly as a timely example of why Steve McQueen’s eschewing of typical dramatic filmmaking for 12 Years A Slave is becoming such a resounding statement this season. Perhaps we’ve outgrown this kind of high-concept atrocity drama and are ready for filmmaking that can find deeper focus amidst scale.

Jerking its tears, The Book Thief delivers viewers another danger-free emotional jaunt through WWII with the help of some unimpeachable performances. It also earns its title by gently pilfering a film’s worth of literary valuables from Zusak’s novel, without finding proper cohesiveness in the translation. At one point in his narration Death says he “is haunted by humans.” This film is haunted by its book.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars