Conquering the Classics

Not long ago Bart realized he needed to expand his horizons beyond sequels and superhero movies. What could be better than tackling the American Film Institute’s Top 100 Movies list? At last count he’s only seen about half of them, so Bart’s goal is to watch all of them in a year’s time, and review every stinking one of them, placing each in their cultural context while bringing a modern sensibility to the viewing experience.

How is it that I’ve never seen Ben-Hur? Ranked #100 on AFI’s Top Movie list, the film’s lasting legacy is certainly the fabled chariot race. It’s bizarre seeing imagery that has become so entrenched in film language in its original form. Ben-Hur is also in the long tradition of swords-and-sandals, a genre of fiction that has never gone away but has had a resurgence in the 21st century with Gladiator and 300. Although Ben-Hur certainly has a grand story, it doesn’t veer into the fantastical like comparable sword-and-sorcery tales that are more medieval in their aesthetic. Instead, it’s grounded in the historical imagination by the ever-present Jesus Christ. Although the Christian Messiah is not a “character”, per se, in this 212 minute epic, his effect on protagonist Judah Ben-Hur is important and emblematic of evolving social standards and expectations in Hollywood and the United States.

How is it that I’ve never seen Ben-Hur? Ranked #100 on AFI’s Top Movie list, the film’s lasting legacy is certainly the fabled chariot race. It’s bizarre seeing imagery that has become so entrenched in film language in its original form. Ben-Hur is also in the long tradition of swords-and-sandals, a genre of fiction that has never gone away but has had a resurgence in the 21st century with Gladiator and 300. Although Ben-Hur certainly has a grand story, it doesn’t veer into the fantastical like comparable sword-and-sorcery tales that are more medieval in their aesthetic. Instead, it’s grounded in the historical imagination by the ever-present Jesus Christ. Although the Christian Messiah is not a “character”, per se, in this 212 minute epic, his effect on protagonist Judah Ben-Hur is important and emblematic of evolving social standards and expectations in Hollywood and the United States.

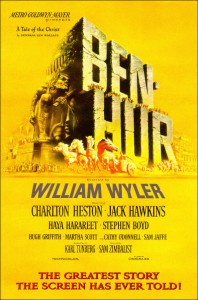

Based on the 1880 Lew Wallace novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, one of the bestselling novels of all time, the story had already been a hit on the stage and brought to the screen twice before in 1907 and 1925. Released in 1959, this film was directed by William Wyler, written by Karl Tunberg (with a number of uncredited screenwriters, including Gore Vidal), and stars Charlton Heston. At the time, with a budget of $15 million, it was the most expensive movie ever made. This was quite the gamble for MGM that paid off with critical acclaim, a $70 million gross, and 11 Academy Award wins that have only been matched by Titanic in 1998 and The Return of the King in 2004. When AFI’s list was first released in 1998, Ben-Hur was actually #72 on the list, but for the 2007 updated list (the list will be updated again in 2017) it fell 28 spaces to allow for new films released between 1996 and 2006.

The story follows Ben-Hur, a rich Jewish prince and merchant in Roman-occupied Judea. When a new governor arrives, along with Ben-Hur’s old friend Messala (Stephen Boyd) who is now the commanding officer of the Roman legions, political unrest leads to trouble. Eventually Ben-Hur is framed and sent to the galleys while his mother (Martha Scott) and sister (Cathy O’Donnell) are put in prison. Ben-Hur, of course, swears he will return and have his vengeance. After years as a slave, he eventually becomes a charioteer, setting up the famous race scene. Amidst all this, Ben-Hur keeps encountering Jesus (Claude Heater) at key moments of the New Testament Gospel, eventually witnessing the Crucifixion and, through that, attaining a kind of emotional and spiritual peace.

Minus the Biblical element, that doesn’t sound far off from Spartacus or Gladiator, or really any warrior-of-antiquity tale following the hero’s journey to the letter. It’s a sprawling tale, covering several years, but it does feel a bit haphazard at times. Ben-Hur having been in slavery for three years is revealed rather jarringly, and his time as a charioteer in Rome is skipped over entirely. This gives the movie an episodic feel that, while certainly a byproduct of the adaptation process, feels truncated and, in the case of Ben-Hur’s relationship with the paternal Arrius (Jack Hawkins), underdeveloped. Still, credit where credit is due, those elements could have been removed all together, but are kept in as building blocks that ultimately lead to the fateful chariot race, and Ben-Hur’s gradual story arc from pacifism to cynicism and vengeance to peaceful, faithful forgiveness.

There’s a fascinating discussion of fate running through the narrative as well, with divine intervention being represented on opposing sides by Ben-Hur’s Judaism and Messala’s belief in the Roman Emperor (and, really, himself) as a god-on-Earth, and Arrius’ atheism and random chance on the other. Certainly the plot is Christian in its leanings, but director Wyler was Jewish (joking at one point that only a Jew could make the ultimate movie about Christ), and intended with Ben-Hur to make a movie that would appeal to all religious faiths. That means that even devoid of doctrine the abstract concept of Jesus as a purveyor of peace and passive resistance works as a meaningful influence on Ben-Hur’s evolution as a character, and makes for some transcendent imagery.

Although Wyler won for best director in 1960, there were criticisms at the time, in both American and French circles, that he was simply a journeyman director. The French New Wave was at its height, with the auteur theory pushing the envelope for what could be achieved in cinema. Wyler certainly doesn’t dally in non-linear filmmaking, forsaking the montage and the flashback (practices made famous by Eisenstein and D.W. Griffith in previous decades, but railed against by Roger Ebert in his 1969 review of Midnight Cowboy). Instead, although his camera can be stagnant at times, simply staging the actors in symmetrical frames in a fashion reminiscent of the theater, it’s all in service of capturing that transcendent image. He understands pacing and the importance of music, with standout examples being the frantic rowing scene preceding the battle with the Macedonians and, of course, the chariot race. Both scenes lack dialogue, with the former relying on the Miklós Rózsa’s thundering score and quick cuts to communicate Ben-Hur’s struggle and the latter being completely devoid of score, with only the hoofbeats and grunts of men projecting the power of each moment.

This all wouldn’t be possible without Charlton Heston. Certainly his acting style is more Old Hollywood, lacking the naturalistic verve of Lee Strasberg’s “Method” that was so popularized by Marlon Brando at the time, but he’s an engaging presence. He and the rest of the cast go broad and stagey, with Heston famously covering his face instead of shedding real tears, but it fits the heightened nature of the plot. Stephen Boyd, in particular, is a standout as Messala, communicating haughtiness and humanity with equal aplomb. His death scene, covered in gore that I didn’t expect for 1959 (although the following year’s Spartacus did have a shocking dismemberment scene) has a fire and intensity that far outshines his peers. Hugh Griffith, the Welsh actor painted up as the Arab sheik Ilderim, is also much needed comic relief in an otherwise grim narrative.

It’s hard to not bring the baggage of 2013 along with me. The religious angle isn’t necessarily exclusive to 1959, as the entire plot hinges on that specific historical period, but it is fascinating to see how it’s handled. The portrayal of Jesus’ teachings isn’t very subtle, with characters like Balthasar (Finlay Currie) and Esther (Haya Harareet) managing to quote the Sermon on the Mount verbatim, but thematically tie in nicely to a story of a man that learns to let go of his hate and anger, a truly universal story. It’s also, from a narrative point of view, completely self contained, as anyone can watch this movie and understand why the characters would be affected by Jesus’ life, as opposed to, say, The Passion, that provides little context for the significance of its plot.

It’s unfortunate, as well, that Ben-Hur never truly veers from the path of the righteous, still showing respect to the scrap of Torah beside his door even when he claims to doubt miracles, being justified in his want of vengeance and not once being corrupted by his time in Rome, so his redemption is never in question. I also expected there to be more of a subversive aspect to the film, having read Gore Vidal’s comments that he injected a “gay subplot” into the film. Vidal was “pansexual” and believed everyone had the potential to be attracted to members of both sexes, so knowing that it’s hard not to read into the early scenes between Ben-Hur and Mesalla. Their open affection for one another and the overtly-phallic nature of their spear-throwing scene led me to believe there would be a hidden love story between them, but almost immediately they turn on one another and there’s great pains to show Messala had a crush on Ben-Hur’s sister Tirzah and Ben-Hur himself is in love with Esther. The one real letdown, regardless of Queer theory, is that Ben-Hur and Mesalla’s friendship is undercooked, with later scenes lacking any hesitancy implying their shared history.

It’s unfortunate, as well, that Ben-Hur never truly veers from the path of the righteous, still showing respect to the scrap of Torah beside his door even when he claims to doubt miracles, being justified in his want of vengeance and not once being corrupted by his time in Rome, so his redemption is never in question. I also expected there to be more of a subversive aspect to the film, having read Gore Vidal’s comments that he injected a “gay subplot” into the film. Vidal was “pansexual” and believed everyone had the potential to be attracted to members of both sexes, so knowing that it’s hard not to read into the early scenes between Ben-Hur and Mesalla. Their open affection for one another and the overtly-phallic nature of their spear-throwing scene led me to believe there would be a hidden love story between them, but almost immediately they turn on one another and there’s great pains to show Messala had a crush on Ben-Hur’s sister Tirzah and Ben-Hur himself is in love with Esther. The one real letdown, regardless of Queer theory, is that Ben-Hur and Mesalla’s friendship is undercooked, with later scenes lacking any hesitancy implying their shared history.

A classic that still holds up today, with beautiful matte paintings putting CGI to shame, compelling characters, and rousing action that remains clear in both geography and stakes, Ben-Hur deserves its place on the list. It would be a shame if it doesn’t make it through the 2017 draft.