The Crop: Year One

The Crop: Year One

The Studio: Columbia Pictures

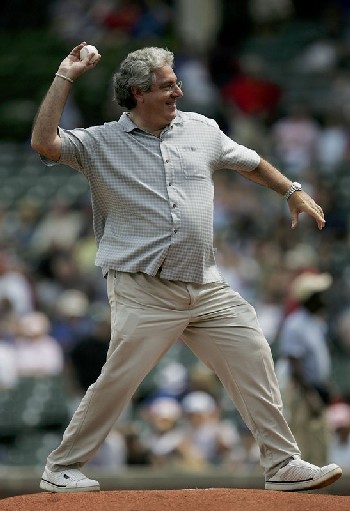

The Director: Harold Ramis

The Writers: Harold Ramis, Gene Stupnitsky and Lee Eisenberg (based on a story by Ramis)

The Cast: Jack Black, Michael Cera, Christopher Mintz-Plasse, Oliver Platt, David Cross, Vinnie Jones and Juno Temple

The Premise: It’s an historical conflation of Biblical distortions! When two primitive men, Zed and Oh, are exiled from their village, they wander forward through history, encountering the likes of Cain & Abel and Abraham & Isaac before settling down in the Las Vegas of the Old Testament, Sodom.

The Context: Years ago, in one of those almost lengthy, almost interesting Sunday New York Times profiles, Judd Apatow referred to himself and his contemporaries as the “Spawn of Harold Ramis”. For Apatow, it was a telling admission. Of all the talented writers, directors and performers to emerge from the comedy chaos of the 1970s, Ramis was the most ubiquitous: he appeared in National Lampoon’s hugely influential stage show Lemmings, spent two years on SCTV, co-wrote Animal House with Chris Miller and Doug Kenney, made his feature directorial debut with Caddyshack (arguably the most quoted comedy in the history of cinema), informed us that “print is dead” as Egon Spengler in Ghostbusters, and, nearly a decade later, guided Bill Murray into his existentialist prime with Groundhog Day. In between these triumphs, Ramis also had a hand in Meatballs, Stripes, National Lampoon’s Vacation, Back to School, Armed & Dangerous (best Steve Railsback cameo ever) and the top grossing film in Estonian history, Club Paradise. Though Ramis was never the sole author of these movies, none of the other National Lampoon/Second City/SNL alumni can claim a more consistent influence on the comedies of the 1980s – and, by extension, the comedic sensibilities of the Gen X-ers who devoured these movies, regardless of quality (no one should voluntarily re-watch Caddyshack II), via pay cable.

Whereas Ramis seemed content to direct, write and/or perform wherever needed, Apatow sought to establish a brand name; he wanted to imbue the loose, rowdy, improvisational aesthetic of Caddyshack and Stripes with genuine humanity. And, being an observant student of these films, he also wanted to ditch the lame plot contrivances – imagine Stripes with more Warren Oates and less Suburban Assault Vehicle – in favor of slightly more believable (or grounded) situations (you may debate amongst yourselves as to which is more plausible: McLovin’s wild night out with Officers Slater and Michaels or Thornton Melon executing the Triple Lindy). Finally, there’s the deemphasizing of Ramis’s overtly antiestablishment sentiments; Apatow’s frazzled characters are too concerned with finding stability to tilt at the powers that be.

But this is Apatow riffing on early Ramis. And early Ramis was, again, little more than a hazily defined piece of a shambling whole (and, from what I’ve read, an organizing influence). No one really took Ramis seriously as a filmmaker until Groundhog Day in 1993, his finest and, sadly, final collaboration with Bill Murray; suddenly, the man who gave us the infamous Baby-Ruth-in-a-public-pool gag was pondering man’s purpose in life and the possibility of happiness. This newfound critical respect earned Ramis some favorable notices for his commercially unsuccessful follow-up, Stuart Saves His Family, and allowed him to weather the complete artistic failures of Multiplicity and Bedazzled. It also helped that 1999’s Analyze This cracked $100 million domestically. What didn’t help was 2002’s dismal Analyze That, which pretty much eroded Ramis’s critical goodwill.

When Ramis roared back to form in 2005 with the deeply cynical heist flick, The Ice Harvest, it was barely noticed (or dismissed outright). Ramis was too far removed from the triumph of Groundhog Day; if he were ever going to direct something other than a zany comedy, he would need a benefactor.

Enter Apatow.

The Script: And here comes a zany Biblical satire that calls to mind Wholly Moses more than it does The Life of Brian.

Granted, it’s an awfully brainy Wholly Moses. Co-written with Lee Eisenberg and Gene Stupnitsky from NBC’s The Office (Ramis directed several episodes for the intermittently great show), Ramis’s narrative begins with the creation of the universe and shoots right into its loopy rendition of the Adam and Eve tale. For Year One’s purposes, Adam and Eve are Zed and Maya, and they aren’t on their own for long; in fact, we soon learn that they’re members of a primitive tribe. Unfortunately for Zed, he’s a gatherer, not a hunter, which makes him undesirable to Maya and just about every other female around. The same goes for Zed’s pal Oh, who has a thing for the highly solicitous Eema.

When it’s discovered that Zed ate fruit from The Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, he is swiftly exiled from the village for having violated the most sacred law of the land. (“Since the Great Turtle climbed from the sea with the Earth on his back, drank the ocean, pooped out the mountains and the first man fell from the stars.”) This, in a way, is fine by Zed; for years he’s been wondering what lies on the other side of the mountain range which, according to the villagers, represents the end of their world. Perhaps there’s more to life than hunting and gathering; perhaps, if he ventures out and makes something of himself, he’ll earn the respect of his people – and get in Maya’s loincloth.

Oh joins Zed on his quest out into the great unknown (and proceeds to get the worst of it from just about every obstacle that gets in their way), and this is where the narrative may confound. The first historical figures the boys encounter are Cain and Abel, who almost immediately get into their fatal dust-up. Having just witnessed Cain kill his brother without much remorse (he proposes to keep the very dead Abel warm by covering him in dirt), Zed and Oh accept the psychopath’s rather insistent invitation to have supper with his family. This almost works out splendidly for Zed, who is offered an evening with Adam’s daughter, Lilith. If you know your Old Testament lore, you probably have an idea as to how this would-be escapade ends. (Oh, on the other hand, shares a bed with Seth, who entertains his guest with a fart cantata.)

Before the boys can get too comfortable, Adam works out that Cain offed Abel, and soon they’re on the run. The next stop is a slave market, where Zed and Oh are briefly reunited with Maya and Eema, who are about to be sold into servitude. After a double cross by Cain, Zed and Oh are on their way to backbreaking, unremunerated labor as well.

Zed and Oh eventually escape from the slave caravan, which brings them to their next major historical run-in: Abraham and the fixin’-to-be-sacrificed Isaac. Our heroes actually prevent Abraham from offering up his son to God, and, after a near-miss on the circumcision, um, tip, they’re on their way to Sodom with the happy-to-be-alive Isaac.

The major failing of Year One is the Sodom passage, which occupies the entire second half of the narrative. Though the writing is still fairly sharp (aside from a dreaded “What happens in Sodom, stays in Sodom” utterance), the momentum of what was shaping up to be a Biblical “Road” movie is extinguished. And while Zed’s epiphany (after being enshrined as the “Chosen One”) is affecting, it’s not quite the finale of Groundhog Day. Or Bedazzled for that matter.

Or maybe it is. Reading Year One, I kept asking myself if I would’ve spotted Groundhog Day as a potential classic on the page. And then I remembered that I didn’t realize it was a masterpiece until the third or fourth time I caught it on cable.

So we’re back to unassuming Ramis. It isn’t quite what I’d hoped for after The Ice Harvest, but, then again, I’m one of eight or nine people who had hope for anything Ramis after that movie.

Why It Might Work: Despite the screenplay’s so-so hit-to-miss ratio, any film with an exchange like the following has the potential for greatness:

Oh: It’d be like sleeping with your mother.

Zed: Which was a big mistake. I see that now. You think it won’t be awkward the next morning but, trust me, you just want to rip your eyeballs out.

What It Might Fail: I compared this to Wholly Moses earlier.

What’s Getting’ Assessed Next: Somethin’ off the Black List.