I want to be friends with Todd Haynes. He’s incredibly smart and funny and very laid back and cool. He’s exactly the kind of guy you could spend hours with having a series of terrific, intellectual but also hilarious conversations. And he’s one of our most exciting and fearless filmmakers, taking cinema to the edge in ways that no other big name has done in decades.

I want to be friends with Todd Haynes. He’s incredibly smart and funny and very laid back and cool. He’s exactly the kind of guy you could spend hours with having a series of terrific, intellectual but also hilarious conversations. And he’s one of our most exciting and fearless filmmakers, taking cinema to the edge in ways that no other big name has done in decades.

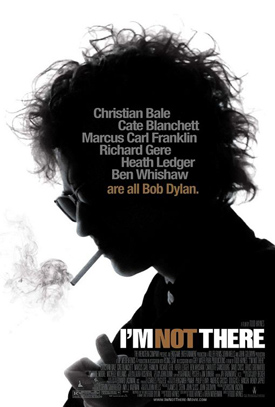

His latest film, I’m Not There, is an absolutely brilliant look at not the life of Bob Dylan but the idea of Bob Dylan. Six actors play different incarnations of Dylan, and I think this method is more faithful to the man than any biopic could ever hope to be. I’m Not There plays like a great Dylan song – cryptic, often odd, but also filled with truth. And utterly engaging, of course.

Haynes did a small press day in LA last week. When I say small, I mean there were five of us with him. I was worried at first, thinking this would be one of those ‘What was it like working with Heath Ledger?’ press days, but the group was smart and canny, and Haynes was allowed to talk about interesting things, theories and concepts.

I’m Not There is playing now in some cities.

Can you talk a little bit about the genesis of this film?

It came in the year 2000; this was a time when I was getting back into Dylan music with a fury. I just had to listen to Dylan. It was an interesting time because I was planning to leave New York for a little while to write my script for Far From Heaven and drive across country, which I love to do. I made all these cassette tapes for myself for the ride. I landed in Portland Oregon, where my sister lives, and there was an empty house where I could work in. I would write Far From Heaven by day but at night I would thirst for more and more Dylan. I was encountering stuff I’d never heard before and reading some biographies and reading a lot of the interviews from 1965 and 66. It was this great time of pure obsession. It was in that moment where this idea, this concept of looking at him as a series of different people, a cluster of different selves, came to me. With that idea came the idea to make a film.

So was it his personal life or his music that obsessed you most?

It was always about the music. But the music and his life were so closely constructing the other. They were in this constant mirroring of the other. I decided the film should be made up of the moments where that was the most true – where the music and his creative imagination and the genres he was getting into were reflected in some way in his life and his activities.

I really had no real expectations that we’d get rights from Dylan, and there’d be no way to proceed without them. And I had another project that was my practical focus. I think that made it better, that I didn’t even really expect it to happen. And then it did. It was just a complete surprise.

Was there something about your life in that period that made you so open to Dylan?

I think it was just about change. I think I needed some change in my life, and I ended up staying in Portland. I fell in love with the city and that whole different environment. Fantastic people. In New York you get very stingy with your time and space; you get very guarded with your time and space. If somebody came to the door and buzzed the door without you knowing they were coming you’d be like, ‘OH MY GOD! THE NERVE!’ I didn’t really like that side of myself, but I saw most people were like that there. In Portland I suddenly felt open to things and people and available. It became this amazing feeling of rebirth. All the people I knew were ten years younger than me. All the people I knew in New York were settling down and having babies, and my life wasn’t like that. I felt like I had more in common with these younger people in Portland. Now of course they’re all having babies and settling down!

Can you talk about collaborating with Oren Moverman on the script?

Oren first came into

the process when out of the blue shortly after we got rights to the

film concept, Jeff Rosen called me up and said, ‘Would you also adapt

this for the stage?’ I was like, ‘What?’ I was still just reeling from

getting the rights for the film, and I don’t think of myself as a stage

guy. I did theater stuff in high school and college, but not since

then. But I started thinking about how the concept of a stage venue

provided things even a film couldn’t, where the characters could share

the stage at times, or share a song. Things could happen that were

interesting. But it was still too much for me to take on by myself, and

I was still about to go off and do Far From Heaven. So I called Oren

up, who is a friend and a great screenwriter, and I said, ‘Oren, will

you help me? Can you do the stage thing with me while I do the script?

We can brainstorm together.’ So he came out to Portland and we had a

brainstorming session on how we might adapt it to the stage, and what

would be the theatrical tropes that we would replace with cinematic

styles. It was just really fun, we both felt like we were imposters in

a medium that wasn’t ours, and that made it even more cool. Then I had

to go off and do Far From Heaven, and somehow this just kind of

disappeared as a real thing. We were hearing rumors about the Twyla

Tharp production, and that’s what this became – which was fine, I had

my hands full. So I proceeded to get into the script, and I worked for

a good year if not more on the script and the research. I had a big

mass of a movie, and so much of the process after the research was

elimination and exclusion. What was redundant, what’s the best way to

make this point when I have twenty examples of it from Dylan’s work.

That’s when I called Oren again and said, ‘Do you want to come and

finish this with me?’ I could have fresh eyes, someone I trust who has

really been on the inside with me and he was there. To make this thing

happen was going to take a lot of people, a lot of creative

partnerships.

Oren is Israeli, but

he found himself getting so into the gospel period, the Christian

period. Even when I found myself being ‘Okay, it can’t be that long,

let’s just move on!’ he’d be like, ‘No! Todd! We have to get into that

more!’ He’d keep writing more scenes.

I read that you were making mix tapes for your actors.

They’re really good!

Can you give us an example?

What were you sending Heath Ledger or Cate Blanchett to help them

unlock their characters? Was it music from the time, was it Dylan only?

For Richard Gere’s

story, for Billy, it was music that spanned many years of Dylan’s life,

but it was all music that reflected his story. There was Basement Tapes

stuff, country music, weird covers of traditional songs that came up in

Dylan’s life, whether it be the Basement Tapes period or covers he did

in the early 90s. And then stuff from his most recent records, like

Cold Iron Bound and High Water were songs that kind of discussed this

imminent sense of Biblical catastrophe looming that was part of the

imagination of that story. Robbie’s mix was all love songs. It’s my

favorite ones and they tell a story – the more optimistic, heart

wrenching ones are at the beginning and the ones about divorce and

conflict from Planet Waves and Blood on the Tracks are at the end. It

ends with Sarah. It’s such a beautiful collection because those songs

are gorgeous. Jude’s is absolutely specific to the Blonde on Blonde and

Highway 61 electric period. It includes live recordings and studio

cuts. Jack’s songs goes back and forth between protest songs and gospel

songs, so it’s an interesting shuffling from one to the next. Woody’s

[Marcus Carl Franklin] are more Woody Guthrie-influenced stuff, Dylan’s

earliest recordings, the Minnesota Tapes. Arthur’s [Ben Wishaw] are the

more visionary songs, the poetic influenced that opened up the

possibilities. Those span the entire career and it begins with Series

of Dreams, which comes much later, and which the film could almost be

called A Series of Dream.

Do you have a favorite Dylan song?

I get that question,

and it’s a hard question to answer, but I’m always content to say Sad

Eyed Lady of the Lowlands, because it’s so epic and so magical and it

always gives me shivers. So sure, I’ll say that one. But there are so

many and they pop up on the iPod and you’ll have forgotten one and

it’ll feel fresh, and other times you’ll be like ‘Not this one again!’

and skip to the next.

Can you talk about your casting process? How did you come to choose these six actors?

Sexual favors. Only way to do it today in Hollywood.

I wish.

No, these actors, I

just love them. I’m so in love with them. Now we’ve been doing press

together… Cate’s been busy, she’s had to do a lot of stuff for

Elizabeth, but she’s so proud of it and she’s so pleased with the cut.

She was so passionate about what I’ve done. Heath has been doing so

much with it… they’re such extraordinary people, and they’re artists.

They want to put themselves in unknown situations and take risks and

it’s not easy. I saw some of them suffer, experiencing bouts of lack of

confidence. Feeling like they’re naked and they’ve never done acting

before, which just showed they were putting themselves on the line for

this, even though the amount of time they needed to spend on this film

was so much less than for a film where they were the single lead, which

is mostly what they do. They just cared so much about what they were

doing.

How involved was Bob Dylan?

He was not involve at

all. He basically gave us permission, gave us the rights to his music

and life. And then he basically carried on with his own stuff, which is

what he does. He just isn’t that interested in stuff about his past and

people’s interpretations. It’s no small feat that he gave us

permission; it was maybe something about what I wrote, or my films that

I sent him, but I think it was mostly the concept made him do something

he had never done before, which was say okay. But from that time on it

was always through Jeff Rosen, who was always a very helpful and

reliable conduit. He’s there to anticipate Dylan’s feelings, I guess,

but mostly that was manifested through a tremendous amount of respect

for my creative imagination.

Has he seen it yet?

I don’t know. I don’t

know. I actually saw Jesse Dylan last night, his oldest son, who was

the one who actually put the DVD in his dad’s suitcase before he

embarked on the latest tour, and he said, ‘I haven’t heard anything,

Todd! I’ll call him again, I’ll ask my dad if he’s seen it.’ But he’s

just doing his thing.

Have you met Dylan?

No.

Did that make it easier or harder?

It didn’t make it harder. It was just something I didn’t need to do, for what I was doing, what I was after.

Each of these aspects of Dylan are so fascinating, but one that I keep going back to is the protest era version, Jack Rollins [Christian Bale]. You take that version of Dylan and have him become the evangelical Dylan. Also you only present him in documentary footage, distancing us from the character. Can you talk about those decisions?

The reason I wanted to tie the protest era Dylan with his Christian period is I found really interesting similarities in the moral and ethical drive that was behind both of those periods in his life. Of course they’re very, very different, and they have different political interpretations, clearly, but that need to have the answer and to be supported by a doctrine and a following characterizes both of those periods in Dylan’s life, as well as an uncustomary lack of a sense of humor. In both those periods of his life he was pretty dead serious. He still did incredible work – the protest songs are among his most famous and enduring and the gospel songs are exquisite – so in a way the music transcended the politics of each. But I felt like it helped me understand the Christian conversion better.

I definitely thought if it was a documentary it would put the Jack Rollins character in a legendary status, out of our direct access, and frame him within a frame in the film. That would give it an extra legendary brand to it. But that same documentary would find him out in real time, in the mid 80s when we imagined it taking place. They would discover what happened to Jack Rollins in the real time of the documentary.

Speaking of finding him out, there’s a scene in the Jude [Cate Blanchett] era where he’s found out as this suburban Jewish kid.

All of these characters run the risk of being unmasked, because they’re all adopting a new guise, a new self, a new narrative that the artist is creating. But that means he’s remarkably vulnerable to being discovered, and that’s very true of Dylan. It’s almost amazing to think of how shocked he would become when people would find him out or reveal truths about his past that he was trying to make fuzzy or more mythical. That felt like an important tension to carry throughout the whole film, which is why at the end the same actor who plays Mr. Jones returns in the form of Pat Garrett to basically unmask Billy the Kid and send Dylan back on the road, back on the train, back into the world.

There’s been a lot made of the six different actors as Dylan, but there’s also very different directorial styles for each Dylan, and within those styles there are a number of homages and nods to other filmmakers.

I sort of realized fairly quickly that all of these psyches of Dylan I was settling on had their roots in the 60s – which made sense to me and an appropriate backdrop – and the way they should be differentiated should come from the cinema of that era. It’s something I always like to do with my films, and it was true of Far From Heaven, where we looked very closely at the cinematic language of these melodramas and particularly Douglas Sirk movies, and try to get inside that practice from that era of filmmaking. I’m a filmmaker, and I’m working in a media that has a long and interesting history, but where the stylistic vogue changes all the time. The 60s – which again, Dylan was drawing from the lifeblood of this period, and it would ultimately draw on his – was an amazing period for cinema as well, particularly European art film, which my film quotes avidly. Ultimately [it was about] finding the voice of the hippie westerns of the late 60s that I think were ushering in that rich period of American cinema that would be the 70s period. They were starting to use these long lenses and flares and a soft palette, a painterly kind of approach. This was more true of movies like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and McCabe and Mrs. Miller than it was for Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, so [cinematographer] Ed Lachman and I were looking more at those first two examples, at least in terms of the lenses and palettes of the Billy story. But yeah, it’s Godard all the way for the Robbie [Heath Ledger] and Claire story, and Fellini – most notably 8 1/2 – for the Jude story.

Chronicles Volume 1 came out while you were getting this underway. Did that have any effect on your approach?

Not really. It blew me away. I thought it was another gift from Dylan to the world. I think it’s just a gorgeous piece of writing. One thing [that changed] the script was Gorgeous George. I loved the Gorgeous George part in Chronicles and I had to have him in the movie. I just thought it was a nice touch. Similarly to his films that he’s associated with, from Masked and Anonymous to Renaldo and Clara – they’re films that I watched, of course, and they’re fascinating and problematic and confusing and they probably affirmed some of the things I was trying to do than even Chronicles did, but they didn’t change what I was doing.

The Scorsese documentary as well as Chronicles sort of demythologized Dylan a little bit. Watching your film I kept think you were remythologizing him. Did that cross your mind, or do you think it crossed his?

I don’t think his approval of mine and his involvement in the Scorsese project, which was actually a project that was long in the making, way before Scorsese even got involved. All the interviews with Dylan and other people were conducted by Jeff Rosen, his manager, and they happened years before he gave us permission [had anything to do with that]. It wasn’t my intent to mythologize him or protect his ambiguity. Well, maybe the ambiguity is in the movie, but to me I felt like each of these stories and each of these places he occupied are incredibly specific and concrete, and he wrote and left behind in each place he occupied an unbelievable amount of work that explains it and exhausts it. There are all these little houses that he built, and they’re all solid, and they’re all very specific and they all have their own architectural style to them, and their own ambience. I wanted to have each of them stand but the way – now I’m really going on this metaphor. I’ve never done this before! – the neighborhood they occupy and the geography of one to the next is not straightforward. There isn’t a perfect linear or teleological connection throughout, but they are all very specific and concrete. To me.

Going with the idea of mythologizing Dylan or not – you have the electric performance at the Newport Folk Festival, and you have the Pete Seeger character picking up an axe and going after the wires, which is something Seeger swears he didn’t really do. Does it matter to you to capture the actual truth or the inner truth of Dylan’s life?

It’s both. It’s a combination, where the two meet. No, Seeger didn’t literally pull an axe off the wall and aim at the cords, but he expressed a desire to do so. What did happen, though, is that the day before when the Butterfield Blues Band, Mike Bloomfield’s band, played they were given a dismissive introduction by Alan Lomax, who was one of the promoters of the festival – I can’t remember if he did it himself – but this was an electric blues band playing at Newport. It wasn’t like Dylan was the first to go electric at the festival. It’s an amazing story – Alan Grossman, Dylan’s manager, who also represented this band, was irate at the dismissive intro, and these two big burly guys got into a physical fight and were rolling on the floor. There was all this dust – they got into a physical fight! And Albert Grossman was always known for his cool-headedness. So that story, combined with the Pete Seeger – at least the stated intention. He was definitely upset and was not happy at the level of the sound and as he would later say was mad that you couldn’t hear the words – to me it all coalesces into a fury and into a state of intolerance about the change in Dylan’s music, how it was deviating from the mandate of the folk ethos. So what I do in the film is not that big a deviation from the truth or making mythic something that wasn’t there.

You know how Dylanogists are – they’re going to come to the film looking for a one to one correlation between what’s on screen and Dylan’s life, looking for exact matches between scenes and characters. Do you tell people to not come to the theater with that, or do you want them to come play with the links?

Well, play, but there’s really no reality. It’s about music. It’s about creation. It’s about an intensely fascinating artistic subject. Reality is such a sad thing to impose on a such a rich body of work and such an amazing period in an amazing life. But I do want people to play and not be burdened by checking off sources and where it all comes from.

You had a longer cut and the Weinsteins wanted you to trim the film. Are you happy with the film at this length?

I am happy with it. It’s long already. It’s just that it’s not long in minutes; it’s just so dense and there’s so much going on. You have to think about the experience of a viewer – how much can they take? There might have been times when I was scratching at myself, wondering if it was better longer. Sometimes it’s more pleasurable to have breathing room – there’s very little breathing room in the movie now. If somebody goes up to pee and comes back they miss twenty chapters. But I had final cut, and Harvey was concerned about length and he had questions about the Billy story, but he wasn’t alone. A lot of people did. I have a process I go through, and it has very much to do with showing cuts of the film to people. It’s not just all my best friends who tell me what I want to hear – that doesn’t help me. I need people to be honest, and we write up our own questionnaires. When it’s a producer or distributor, they have their process of vetting how a film plays, and it’s usually the classical testing process. My films don’t test – they usually test very poorly. They do not reflect how the films are regarded. There’s no relationship. Far From Heaven got 19 out of 100 on the testing score, and then at the end of the year when they add up the reviews, it was the best reviewed movie of the year. It was the most successful of my films at the box office as well. I know my films need contextualization, and they need the press to set the films up for the world. This film actually tested 45 out of 100, the highest any of my films had been scored.

Fluidity of identity is a big part of this film, as it is in glam rock. What do you see as the connection between Velvet Goldmine and I’m Not There?

There’s a lot of really interesting similarities, but I think there are fundamental differences. One of them has so much to do with British traditions, a self conscious, ironic relationship with identity and the pose. The Oscar Wilde idea of the pose. Inverting provided wisdom and common beliefs, and playing around with those inversions. Very much to do with homosexuality, gay sexuality and bi sexuality. [I’m Not There] to me is so very American. Dylan embodies these different phases of his life not in a self conscious ironic way, where he’s planning it out and it’s about dressing up and painting your face. He is like some Method actor or some amnesiac who basically completely enters these phases and almost makes himself forget what happened before. There’s something very American in that, in that we are kind of exuberantly innocent all the time. Even when we uncover our hypocrisies, it’s like we never knew they were there before. ‘Oh my God, slavery! SHOCKING!’ The thing is that we keep repeating our own revelations. It’s a much less reflective and analytical procedure, this one, but it’s completely fascinating and I think intensely American.