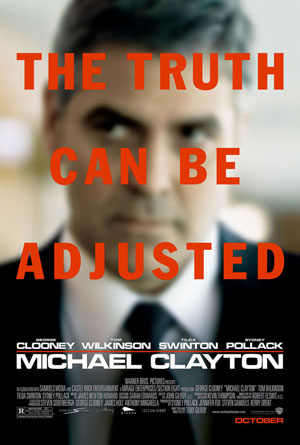

Michael Clayton feels like an exercise in restraining everything you like about George Clooney. It’s as if Tony Gilroy woke up every morning and asked himself, ‘How can I make the most personable and charming leading man of this generation dull and plodding? How long must I hold his charisma under the tepid water of my movie before it finally really drowns?’

Michael Clayton feels like an exercise in restraining everything you like about George Clooney. It’s as if Tony Gilroy woke up every morning and asked himself, ‘How can I make the most personable and charming leading man of this generation dull and plodding? How long must I hold his charisma under the tepid water of my movie before it finally really drowns?’

This isn’t to say that Michael Clayton is a bad movie. Which isn’t to say that it’s a good movie, either – it’s mediocre at best, a film that does not have half as much to say as it thinks it does, and that mauls its own narrative to hide that fact. Michael Clayton opens at the ending, with the titular corporate fixer gambling in an illegal poker game before being called off to deal with a client who just engaged in a hit and run. Weary and drained of life and conviction, Clayton’s advice to the guy is essentially ‘You are fucked’ – not quite the intro to a high powered fixer I expected. Then he goes for a ride, stops to look at some horses (really) and his car blows up. Time to flash back!

Gilroy, who wrote and directed, has stabbed his film in the heart right at the beginning. I love starting in media res, and I can stand films that open with some action before flashing back to See How We Got Here, but Gilroy doesn’t flash back far enough. Or he opens his film too late. Either way, the difference between the Clayton at the beginning of the film and the Clayton at the beginning of the story isn’t big enough. It’s like we’re only coming in at the last bit of this guy’s fall, which would have been okay if the gimmicky narrative of the movie didn’t keep me constantly wondering why his car blew up – since nothing else interesting happens for forty-five minutes.

Clooney trudges through the film like a man with a head full of cough medicine; Clayton’s undergoing a load of personal crises at the moment, and the irony is supposed to be that the guy who fixes problems for a living can’t fix his own. Except that we don’t see him being master of his universe. It’s like Gilroy hired Clooney as the shorthand for storytelling – ‘Hey, you know how Clooney usually is? Look at how run down he is in this film! That’s all!’ The latest case that Clayton has been called in to fix is the sort of problem that only originates in the word processor of a screenwriter: the head counsel for a chemical company in a long, ugly and evil case about small town people being poisoned has gone off his meds and during a filmed deposition stripped naked and confessed his love to one of the women affected by the cancerous poison.

Tom Wilkinson does his damnedest as the bi-polar lawyer, but Gilroy saddles him with speech after speech that sounds like screenwriter-ese. Gilroy has said that he was inspired by Network, but his attempts to capture Chayefsky-esque monologues fail, as does his whole tone. Is Michael Clayton a satire? The over the top Wilkinson stuff seems to think so, and maybe some almost-wacky hitman moments, but the rest of the film never even ventures near satire, unless having Clayton deal with his boring-ass family is some level of black comedy so dark I couldn’t see it. Looking back at it now, I would have liked to see a Michael Clayton done more in the tone of Network, but the reality is that the way Gilroy has written and shot his film makes you sea sick from lurching between one tonality and the next.

I would have also liked to have seen a Michael Clayton that gave Tilda Swinton just a little bit more. She’s got a terrific role as an executive at the chemical company thrashing about in an effort to solve the looming crisis in the lawsuit, and as always she’s terrific in it, but there’s a sense that she’s just getting shorted a tiny bit, like one more scene would have elevated her from really good to Oscar nominee. And she could still take a nom – she would certainly deserve it just for the scene where she’s getting dressed and practicing a promo interview in the mirror – but I feel like the movie denies her the one killer moment she needs.

Maybe the problem with Michael Clayton is the same that faces Network in 2007 – this shit does not seem like it’s all that out there. The events of Network, right up to the killing of Howard Beale on television, feel more and more ripped from yesterday’s headlines. And the ohmigod concepts of Michael Clayton – evil corporation willing to go to any… ANY!… lengths to keep from losing money in a lawsuit – felt old when A Civil Action did modestly okay. It makes the movie feel sort of like that kid who just found out the CIA suppressed democracy in Iran: hey, we’ve all been waiting for you here for some time, and none of your insights are new. Maybe Gilroy needed to make the villainy of the corporate types bigger to match the wackiness of Wilkinson’s character. Maybe he needed to make Michael Clayton a character who didn’t have a rain cloud over his head the whole film.

There’s nothing sadder than a prestige picture that just doesn’t work, because these kinds of films so rarely allow themselves to have fun. That means if the heavy, serious, important and actorly moments don’t connect, you’re left sitting through a movie that ponderously plods along from prestige point (a breakdown and monologue!) to prestige point (a long shot in the back of a cab that gives our star the opportunity to present his whole inner life only on his face!) with little joy along the way.