As announced on Saturday, this was the winner of TIFF ’07’s People’s Choice Award. Way to go, Canada!

As announced on Saturday, this was the winner of TIFF ’07’s People’s Choice Award. Way to go, Canada!

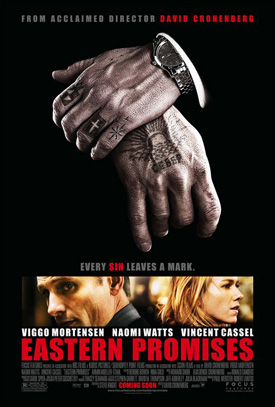

With Eastern Promises, David Cronenberg has made the most accessible film of his career. Applying long-standing interests in transformation and duality to familiar subjects (gangsters and their victims) he’s turned out a tale of mafia machinations that prizes simplicity and craft as highly as brutal violence; certainly all are present in equal measure.

Thirty years after releasing a film that was arguably a singular moment in elevated exploitation (Rabid) Canada’s most famous auteur is once again working with exploitation. This time, as a subject rather than methodology. When a young Russian woman dies while giving birth the protective midwife Anna (Naomi Watts) takes her diary, employing her uncle (and ex-KGB stringer) as translator in hopes that the book will lead to blood relatives for the surviving infant.

Passages within lead Anna to a restaurant and encounter with the proprietor’s grandstanding son Kirill (Vincent Cassel) and Kirill’s driver Nikolai, for whom Cronenberg once again enlists Viggo Mortensen, increasingly a Gibraltar of an actor. Both men are associated with the Vory V Zakone, an arm of the Russian mafia, in service to Kirill’s father Semyon, played with a deceptive affability by Armin Mueller-Stahl. Intimations of sexual slavery soon arise; the orphan may be the child of rape or forced prostitution.

Cronenberg’s career was once visually characterized by latex and malleable flesh; now his calling card is surgical precision. Eastern Promises may be the most efficient gangland thriller ever made. There’s not an inch of fat, as every frame of film moves the story forward. It’s quietly awe-inspiring to watch a director move with such grace and surety from one stripped-down scene to the next.

Anna’s protective instinct for the orphaned newborn and Nikolai’s seeming attraction to her are wrapped up into a vision of mob violence and power struggles that sidesteps tropes and story beats we’ve come to expect from gangland legends. As in A History Of Violence, Cronenberg’s fascination with dual natures plays out in the public and private faces of Nikolai, Kirill and Semyon, and transformation comes from the ink signifying status within the Vory V Zakone.

Cronenberg’s old obsession with the body and means of altering flesh may have been muted in the past decade, but echoes ping through Eastern Promises. The gang and prison tattoos that garland Viggo Mortensen’s hands and body are semaphore code for his criminal history; in the Vory V Zakone you can perform admirably and achieve respect, but you’re not a made man until you’ve been allowed to inscribe stars on shoulders and knees.

Then there’s the scene that’s as sure to etch Eastern Promises in memory as the sex scenes did A History Of Violence: a brawl in a tiled bathhouse sees Viggo facing off fully unclothed against two Chechnyan thugs. Cronenberg is never one to shy away from violence though he accepts the sight of bruises and blood rather than relishing them, and this scene is drawn out to an almost uncomfortable extreme. Expect the audience’s kicking and struggling at the end to reflect the action on screen.

At a festival like Toronto a full-frontal fight scene doesn’t seem so outrageous; particularly this year, when Young People Fucking is a high profile title and male actors from Heath Ledger (I’m Not There) to Lee Kang-Sheng (Help Me Eros) are proudly acting not just commando but, you might say, classical Greek.

It’s another story altogether in the multiplex. Viggo’s nude fight scene makes Nikolai look like a fighter able to come out on top (just leave that alone, please) despite great vulnerability, but also makes Viggo appear to be one of the most courageous actors working today. Though he’d likely avow that adhering to a Russian accent for the duration of a feature is more intimidating; he pulls that off well, too.

Steve Knight’s script, unfortunately, is almost as stripped-down as Viggo’s fight scene. There’s obviously a lot to be praised in elegance, but from a director less confident with actors and the camera Eastern Promises would seem as pallid as the faces of Viggo’s defeated assailants. It certainly makes little sense that Anna would ever be allowed to live beyond her second encounter with the Vory V Zakone gang. Knight’s attempts to justify Anna’s actions are elevated by Cronenberg’s sure touch with his four leads, but never quite made as lifelike as the interior life of the mafia.

There’s also a pale attempt at a twist, or what might have seemed like one on the page. Cronenberg has never bought into the twist — he resists the Shyamalanization of third acts at all costs — and as in A History Of Violence, doesn’t allow the film to submit to the indignity of a faux shocker reveal. His approach is that what would be a twist elsewhere should be an inevitable piece of story driven by character, and that’s almost the case here. Even so, Knight’s would-be twist is a trope the size of a red London bus, and Cronenberg is at least grazed by the bumper.

The director has also rarely been one to write or characterize outright villains in his films, which might account for why William Hurt’s gangster in A History Of Violence seemed so over the top. For the audiences turned off by that performance, I present Armin Mueller-Stahl. As Semyon, the actor is blankly ferocious and unburdened by compassion. Mueller-Stahl makes an exceptionally chilling adversary, and offsets some of Knight’s attempt to eke extra pathos out of Anna and her maternal instinct. Ironically, Semyon humanizes the film more than any other character, lending a deep-rooted unease to what might be David Cronenberg’s New Exploitation.

8.1 out of 10