"There is a large, loud question right at the center of “Cruising,” and because the movie lacks the courage to answer it, what could have been a powerful film dissipates its force and leaves us feeling merely confused and annoyed. The question is: How does the hero of this film, an undercover New York policeman, ultimately really feel about the world of homosexual sadomasochistic sex he is assigned to infiltrate?" – Roger Ebert, 1980

"There is a large, loud question right at the center of “Cruising,” and because the movie lacks the courage to answer it, what could have been a powerful film dissipates its force and leaves us feeling merely confused and annoyed. The question is: How does the hero of this film, an undercover New York policeman, ultimately really feel about the world of homosexual sadomasochistic sex he is assigned to infiltrate?" – Roger Ebert, 1980

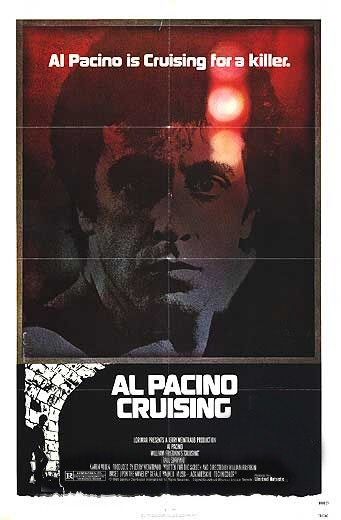

Lost amid the renewed hubbub over William Friedkin’s Cruising, the gay serial killer flick which makes its long-anticipated/feared debut on DVD this Tuesday, September 18th, is the incontrovertible fact that, for all its queasy-making content, the film is still stunningly squeamish when it comes to the idea of its protagonist having sex with another man. For an inveterate flouter of standards like Friedkin, this timidity is curious; he’s certainly not shy about depicting the more notoriously outré behavior favored by the gay S&M underground during the pre-AIDS era, as evidenced by the film’s envelope-shredding "highlight" of a man being fist-fucked in the middle of a nightclub. But these are periphery perversions; Pacino’s only watching. And he never partakes. Late in the third act, just when it looks like the viewer is about to watch one of the most popular actors of the 1970s get it on with another man, Friedkin abruptly opts to resolve the picture’s murder mystery element. Whew!

That he fails to resolve it satisfactorily – Friedkin throws the audience off with the discovery of yet another murder that may implicate Pacino’s deep undercover cop, Steve Burns – further exposes the film’s lack of thematic focus. Combine this with the half-assed police procedural – via Gerald Walker’s novel, but reconfigured by the on-duty peregrinations of NYC Detective Randy Jurgensen – that provided Friedkin an excuse to examine a socially aberrant subculture that clearly fascinated him, and Cruising should be as easy to dismiss today as it was in 1980. But there’s a roiling, unsettling texture to the film that cannot be denied; it may be fatally flawed (Friedkin admitted to me that the dual father-son conflict which besets both Burns and the serial killer, Stuart Richards, is a Freudian non-starter), and it may play up the kinds of homosexual stereotypes that plagued the community for years (e.g. the running "Blue Oyster" gag in the Police Academy movies wouldn’t exist without Cruising), but there’s something genuinely compelling about this movie. One doesn’t need to like Cruising to take it seriously as an absorbing piece of cinema. Accounting for why it’s absorbing, however, ain’t exactly easy.

Friedkin was three years removed from the most exhausting filmmaking experience of his life, Sorcerer (a superb remake of Wages of Fear that’s also on tap for a DVD reissue), when he took on Cruising. After the agreeably entertaining caper flick, The Brink’s Job, Friedkin the provocateur was ready to plunge mainstream audiences into a heretofore unseen world of leather, whips, chains and amyl nitrate-fueled hook-ups. To best achieve this immersion, he received permission to shoot in many of New York City’s most notorious S&M bars, which bore ominous monikers like The Mine Shaft or Ramrod. And when it came to capturing what went on in these sweaty, dimly lit establishments, he didn’t flinch; indeed, Friedkin and cinematographer James Contner depict happenings like "Precinct Night" in all their nightstick fellating glory.

The problem with Cruising is that there’s only one seemingly sane gay character fluttering around the outskirts of this world, and he’s not only insubstantial but completely abandoned once Burns begins to make headway into his hunt for the killer. Though it does at first feel like the character of struggling playwright Ted (Don Scardino) has wandered in from a more honest dramatization of post-Stonewall gay Manhattan, he’s also the audience’s best chance to perhaps understand the allure of the leather clubs and, most crucially, get to know Burns, who remains closed off to his girlfriend (Karen Allen) and superior officer/mentor (Paul Sorvino).

Once Ted disappears, Cruising turns into a Big Gay Tour through hell, and this is precisely why the film is still largely reviled by that community. The deliberate suspense built by Friedkin in each of the film’s intensely disturbing murder sequences hinges on two things: the inevitability of violence and the possibility of seeing two men fucking. To Friedkin’s credit, the former element is excruciatingly effective because, at the time, he’d already proven that he didn’t give a shit about taking care of his audience. And it pays off brilliantly in the first murder, where Friedkin shoots the killer drawing his knife along the back of the actor and plunging it in all in one take; the startled reaction of the actor enhances the viewer’s sense that they’ve just watched an actual stabbing. But it’s impossible to not resent Friedkin for playing up the horror/titilation factor of gay sex – which, at the time, was as big a taboo as reelecting Jimmy Carter – as a means of throwing the audience off balance.

This doesn’t mean Friedkin personally found the concept of gay sex off-putting; it’s his opportunism, which did nothing but reinforce cultural hostility toward homosexuality, that’s objectionable. This is why it’s tricky to suggest that Cruising is somewhat more palatable today than it was in 1980; even though many Americans now understand that not all gay men scurry off under the cover of night to cramped underground bars named after euphemisms for buttholes, the film is still savagely insensitive. But the surface of it is so haunting (particularly Jack Nitzsche’s desolate electronic score) that one can’t help but watch. It may not be defensible (at least, not in my estimation), but it is to be experienced. And while Friedkin’s now invoking everything from the looming AIDS epidemic (he’s talked of "mysterious deaths" that weren’t reported until 1981) to the ambiguous finale (even though he chided me for claiming that the film had an ambiguous narrative), what he should really do is clam up and let a new audience comprised of people who’re unfazed by homosexuality have their say. There’s no undoing the past, but there may be a future for Cruising that doesn’t entail its being a pop cultural punch line. Considering the film’s previous critical reputation, that’s progress.

The "Deluxe Edition" of Cruising (is it too late to rechristen that the "Party Size Edition"?) hits the DVD retailer of your choosing September 18th.