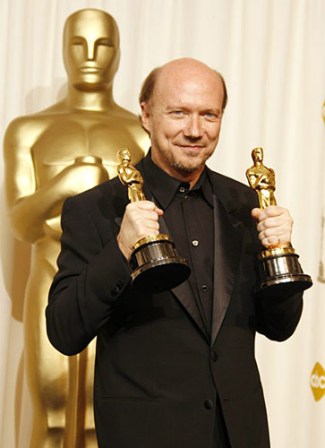

Paul Haggis is one of the most divisive artists of our era, and not just because of his politics. After Crash, his microcosmic examination of race relations in America, shocked many industry observers by winning the Academy Award for Best Picture in 2006 over Ang Lee’s generally favored Brokeback Mountain, Haggis has been either hailed or derided for his bluntly confrontational style. It’s not so much about what he’s saying as how he’s saying it: some find his candor refreshing; others find it heavy-handed. All that matters to Hollywood is that they’re finding it: the low-budget Crash grossed a surprising $54 million at the domestic box office, while the six movies he’s scripted have combined to tally an impressive $381 million.

Paul Haggis is one of the most divisive artists of our era, and not just because of his politics. After Crash, his microcosmic examination of race relations in America, shocked many industry observers by winning the Academy Award for Best Picture in 2006 over Ang Lee’s generally favored Brokeback Mountain, Haggis has been either hailed or derided for his bluntly confrontational style. It’s not so much about what he’s saying as how he’s saying it: some find his candor refreshing; others find it heavy-handed. All that matters to Hollywood is that they’re finding it: the low-budget Crash grossed a surprising $54 million at the domestic box office, while the six movies he’s scripted have combined to tally an impressive $381 million.

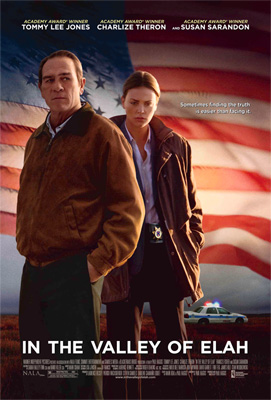

America is all exposed nerves at the moment, and Haggis seems determined to work each and every one of them; thus, after tackling racism in Crash, euthanasia in Million Dollar Baby, and the human cost of wartime propaganda in Flags of Our Fathers, Haggis has at last moved on to the biggest argument starter of ’em all, Iraq, with the confidently mounted In the Valley of Elah. Starring Tommy Lee Jones as Hank Deerfield, a proud ex-military man investigating the mysterious disappearance of his son who’s just returned home following a tour of duty in Iraq, Elah uses the conventions of the police procedural as a means to investigate the psychological toll of urban warfare. Emotionally, it’s also a father-son tale in which the former comes to realize just how little he knew the latter.

Though more classically structured than Crash, Elah is nevertheless another "social problem picture" through which Haggis hopes to provoke debate and, most importantly, effect change. In speaking with him a few weeks ago at the Beverly Hills Four Seasons, I found the Oscar-winning filmmaker to be genuinely concerned with the welfare of our enlisted men and women; like most Americans, Haggis is angrily dissatisfied with the care our troops are receiving upon returning home, and Elah is his way of asking the kinds of questions that might motivate the public to shame its government into action. This is the way Haggis operates: his art isn’t merely informed by his conscience; it is his conscience.

As this makes Haggis sound like the most humorless bastard on the planet, it’s important to stress that he’s actually a very affable guy. He’s also incredibly gregarious; I got the feeling that he could’ve sat in that hotel room and vigorously hopped from one topic to another for the entire afternoon. But while he’s certainly a man of many opinions, he’s also quite curious. Before I could get the tape rolling, he was peppering me with questions about CHUD and internet journalism in general. He had just expressed his enthusiasm for the democratic nature of the medium when I finally hit record.

Q: There’s also the downside, where it gets too democratic and there are too many voices, many of which are uninformed.

Paul Haggis: Oh, yes. There are a lot of loonies out there. The thing I find about the internet now that I’m quite uncomfortable with is that the cynical voices have sort of taken over the internet. That’s why we have a lot of reality TV which is about torturing people. It might be a reaction to what’s happening politically and feeling like we have less and less power. There’s that story in the movie that I got from an animal rights activist: there was this kid who was accused of torturing chickens at a slaughterhouse. It’s completely true, and it’s what happens a lot: these kids who work in slaughterhouses get paid minimum wage, and, after a while, you kill enough chickens that you become inured to that kind of violence pretty quickly. And then you start poking their eyes out and having "fun". And you do it because you feel so powerless. Our baser nature is to take it out on something that has less power than us. That’s why bullies pick on kids, and kids blow up frogs.

Q: Viciousness toward animals has been in the news lately, what with Michael Vick and his dogfighting indictment. There’s been an intensely negative response toward Vick, but some people are still working through it. Their defense runs along the lines of, "Well, we shoot deer!" And I’m like, "Fighting animals to the death is something else entirely." But what fascinates me is why is this incredibly rich man participating in this? And if you’re comfortable with torturing and killing dogs, what’s the next step?

Haggis: Exactly. And that’s why I wanted to use the chicken story in the film. This is not something that’s isolated. How do you become inured to that kind of violence? And then compare that to what these kids have been experiencing [in Iraq]. I had a couple of Marines over at my house yesterday morning for coffee. We were talking about the film. These are proud Marines. These are guys who really wanted to serve their country. And decorated soldiers, not lower-ranked guys. And one of them said, "You know that scene in your movie where they [play around] with the burnt bodies in that bus? We came across a body just like that. We all took pictures with it, put our arms around it, and put a hat on it. It wasn’t until I got home and saw those pictures that I said, ‘Holy shit, what was I doing?’" At the time, you see enough of that. When you’re in the center of that, and people are trying to kill you, you’ll make terrible decisions. It feels normal. It feels like the right thing to do. "It’s black humor. We’re trying to deal with it." And you are. The mind is trying to cope.

Q: It’s survival.

Q: It’s survival.

Haggis: It is in an odd way. And it’s fine as long as you stay in that state forever. As long as you’re always at war, you’ll be fine. (Laughs) But come home, and then see what happens to you. And that’s what’s happening to our men and women. There are 52,000 cases of PTSD (Post-Tramatic Stress Disorder) reported. Those are the ones that the Department of Defense says, "Yes, these are cases of PTSD." So there’s got to be, what, 200,000 to 300,000 more? Because it’s a real stigma for anybody to admit this. A solider yesterday was saying, "When I went in for help, my immediate senior, who was on the same career path as me, said, ‘You have two choices: you can get help or have a career.’" So he didn’t seek help, and he ended up going nuts in Iraq. They brought him in, and he finally saw an Army psychiatrist who said, "Yes, you desperately need help, and we’re going to get you help." What the Army did was throw him in the brig. They put him in solitary confinement for three months with a straitjacket and a helmet. That was their treatment.

Q: You’re kidding me.

Haggis: Now, this is one of their top guys! This isn’t some screw-off. This is a tough son-of-a-bitch who’s there fighting and doing all of this stuff. He was an officer.

Q: So piling trauma upon trauma was their way of helping him?

Haggis: Yes. When they brought him home and released him, he went back to them and said, "I have PTSD". And they said, "Nope, you have a pre-existing behavioral condition. You brought this with you. The war had no effect." This is, again, somebody who was promoted three times during boot camp; he was so good at what he did. And he’s a nice, sweet kid. But he had a "pre-existing behavioral condition." And out of that 52,000, only 20,000 have been allowed help because the other 30,000 have pre-existing behavioral problems.

Q: Do the Marines that you talk to feel like it’s been worth everything they’ve incurred?

Haggis: I didn’t know how marines and soldiers were going to react to this film; that’s why I wanted to show it to them right away. So we took a rough cut out. We showed it to a lot of them. If they all hated it, I wanted to be prepared. Obviously, I was still going to finish the movie and release it, but I wanted to be prepared. And like 99.9% were very positive toward the film. They say, "This is the experience. This is what’s happening to us. This is what happened to our buddies. And we’re very glad you didn’t make this into a political film." I think it is a political film, but it isn’t a partisan film. We don’t come in and say, "The Democrats were right from the very beginning!" That wasn’t the point of the film. And I think the soldiers really liked that. Some believe that it’s the right thing to be there, or at least they went there for a good reason. Others believe it’s a terrible thing. They’re really split down the middle.

Q: The film is definitely incendiary. It’s coming from a place of anger, and that anger seems to be incited by the fact that there is an overriding moral wrong being committed. Morally, something has been done wrong in conjunction with this conflict. In the two films that you’ve written and directed, you really are concerned with moral issues. And you do it within a framework of what I believe is the modern equivalent of the social problem picture: the kinds of movies that were very popular in the early 1960s, the 50s and even back into the 40s with Gentlemen’s Agreement and so on. They’re films that tackle these societal problems in a very blunt manner.

Haggis: What I try to do is make a really entertaining picture that talks about some of these things that deeply concern me. As you said, there’s a long history of this; it’s not like I invented it. And, yes, I like it. I think moral quandaries make great drama. And, yes, you can just run off and do a moral quandary about whether you should cheat on your wife or not… and, you know, that’s good drama, too! I’m probably going to do one of those next; I’ve got a little romance I want to do. But Crash… who the hell knows where that came from! That was just me sitting around, and the experience of living [in Los Angeles] for thirty years starting to overwhlem me. So I wrote that story never thinking it would be anything. I didn’t know what it was – maybe a TV show. But then [Bobby Moresco] and I got together. It wasn’t like a master plan.

With [In the Valley of Elah], because of what was happening in Iraq and our soldiers was so monstrous, what we were asking them to do was so impossible… I felt the need to do something about it, to address that issue and ask questions about it. Because our government, Democratic and Republican, are really good at keeping this stuff out of the news. They don’t want us to be thinking of these things. They want us to be thinking about simplified issues we can vote on. "Gay marriage! That’s what’s important!" It’s like, "What!?!? What is that!?!?" But that’s what we have to have elections on, not that we’ve undertaken urban warfare. I mean, did we not learn from thousands and thousands of years of history about this kind of warfare? About what urban warfare is like, and the toll it takes not only on the villains we’re trying to kill, but the population we’re trying to get through to kill them and our own soldiers. We thought Vietnam was bad. What these very brave men and women have to put up with, most of whom are there for what they believe are the right reasons. Maybe a few guys go wanting to get the hell out of some small town (laughs), but even then, no one goes over there thinking, "I am going to do wrong. I’m going to kill civilians." Who thinks like that? But that’s what you’re faced with in urban warfare. And we act like didn’t know this?

Q: And as a filmmaker, you kind of take a direct address to the audience. It’s a very blunt approach. "Over the course of this drama, we are going to address these very serious issues." Characters will voice messages that you want the audience to walk out with. And there’s a criticism that you’re telling us what to think rather than figure it out for ourselves.

Q: And as a filmmaker, you kind of take a direct address to the audience. It’s a very blunt approach. "Over the course of this drama, we are going to address these very serious issues." Characters will voice messages that you want the audience to walk out with. And there’s a criticism that you’re telling us what to think rather than figure it out for ourselves.

Haggis: I think Crash is very different from this one. In Crash, characters said things that no one in their right mind would say. I didn’t know if Crash was a movie or not. It was a bunch of stuff where I said, "You know what? I want to mess with people! I don’t care if it’s a movie or not; I just want to mess with people. I want to turn people around in their seats. I want them to leave that theater spinning." I don’t know… I figured if people paid ten bucks [to see it], it was a movie.

[In the Valley of Elah] was much more classically structured and classically shot because I wanted to talk about America. So it’s shot like a John Ford film. (Laughs) I really wanted to tell the story through a character whose point of view is very different from mine, whose experiences are very different from mine, someone about whom we’d go, "That’s an American. We’re proud of him. Yes, he has flaws, but we know him and we respect him and, in some way, we want to protect him. We don’t want him to have to see the horrors that are really out there." There’s an innocence in that character, that John Wayne or Henry Fonda character. So that’s what I wanted: a character we want to protect. And tell that story through his eyes rather than mine.

Q: Although he is of the Vietnam era. They’re not new to atrocities.

Haggis: Still, there are many folks out there that came through Vietnam who strongly believe that what we were doing there was right. They’re very proud of their service, and are very America and the values we hold here. Yes, he came through Vietnam, but if you go to the heartland, you’ll find a lot of people who still believe in the values Hank believes in.

Q: It’s strange to see how, even today, people will say "We were one surge away from winning Vietnam!"

Haggis: It’s ridiculous. It was a stunning and embarrassing defeat, and we all know this. But, yes, it’s history. You have to constantly try to rewrite it, don’t you? That’s why I ask the question of David and Goliath in this, because I know that history is told by the victors. I was fascinated by the David and Goliath story because you have this kid… he was a kid who came in and said, "I will fight this giant." So the king gives him this armor that’s too big, and David goes there with five stones in his hand to fight this giant that all the king’s soldiers and champions won’t fight. He’s so brave. He stands there, he knocks this guy down with a stone, and he wins. And I thought, "As brave as this kid is, what kind of king would send a kid to fight this giant?" He’s going to get killed, right? And all these warriors are huddled back saying, "You go kid. You don’t need an army. Just take these stones and you’ll be fine." Well, yeah, he killed the giant. He was incredibly brave and, probably, incredibly lucky. But, knowing history, I also asked myself, "Okay, this standoff went on for forty days. I wonder how many kids the king sent out into the valley before David. All these kids we’ll never know about. Kids who were brave, who threw their stones, and were just crushed." History is funny. It tells the stories we want them to tell.

In the Valley of Elah opens in limited release this Friday, September, 14th. It will expand throughout the rest of the month.