I have interviewed Paul Greengrass more times than I have interviewed anyone else ever, and I have learned one valuable thing: when talking to this man, get out of his way. Paul will hold forth on a topic for a long time, and you just let him go with it because it’s never blustery or long winded – the guy has something to say. Always.

I have interviewed Paul Greengrass more times than I have interviewed anyone else ever, and I have learned one valuable thing: when talking to this man, get out of his way. Paul will hold forth on a topic for a long time, and you just let him go with it because it’s never blustery or long winded – the guy has something to say. Always.

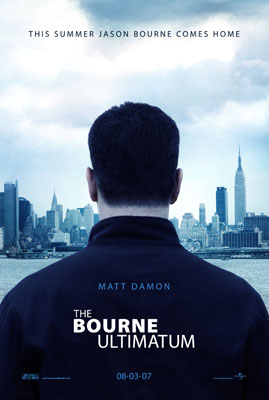

This latest round took place at the Four Seasons in Beverly Hills, after I had seen what is easily one of the very best films of this year, and without a doubt the best action film I’ve seen in a long time: The Bourne Ultimatum. Paul had been working on the film right up until the last second; in this interview he mentions tweaking things on Thursday night – I saw the movie on Friday night. But unlike the junket interview I did with him for United 93, where he seemed exhausted and worn down by the emotions of that project, Paul was fresh and excited, even having worked so long and hard on the film. It’s obvious that these movies energize him, recharge a battery in him, and I hope he keeps that battery charged – it’s obvious that Paul Greengrass is one of the top directors working today.

I feel like this may be the most consistent trilogy of all time. When you started this one, did you begin with Supremacy and go from there, or did you approach it fresh?

I watched Identity and Supremacy back to back. That’s kind of where you see where you need to go. You see straight away in that final scene in Supremacy he’s arrived in New York – clearly a while later after Moscow – and it’s a perfect end to Supremacy. But when you watch the two films in a row with a thought to the third, you can see something must have brought him to New York. Something must have happened after that phone call. That’s what gave the shape of Bourne Ultimatum. It was an attempt to answer that question. Once you ask yourself, what brought him to New York?, the answer has to be The Answer. He must have gone there because he thought he would find The Answer.

[The following question and answer contain some spoilers. Swipe to read]

What’s interesting is that in the end the answer he gets isn’t even the one that we’re expecting. The answer isn’t that he was coerced, that he was kidnapped, the answer is that he volunteered and then he made a very conscious choice. How important was it for you that he wasn’t brain washed, that he chose to sit up and shoot that guy in the corner of his own free will?

Vital, I think. It’s like any quest story, the journey is ultimately the most important thing. And the true quest into identity cannot have an easy answer. What he learns is that, most importantly, while at the end of Supremacy he learned his name, identity is about much, much more than your name. If I told you my name, it wouldn’t tell you about my identity. Identity is a moral identity, what kind of a man was I? Was I a killer or did they turn me into a killer? Those are the sort of issues, and for the character to work you have to feel that it’s not easy for him. If he just found out that they had brainwashed him, it would be a cheat. It would remove from him the responsibility for his dark past. I think the fundamental appeal of the character rests on the idea that he has courage enough to confront the darkness of his past and renounce it in order to walk towards the light. He’s a character in search of redemption; a very moral character, Bourne, which is why I think he’s so contemporary. The morality is there, but never stated. Innate.

One of the main thematic elements of the film is the surveillance society that we live in. I couldn’t help but think about the role CCTV had in catching the people involved in the recent London attempted car bombings and the Glasgow airport attack.

They tracked the cars that attacked the airport, literally tracked them in real time.

On one hand the film shows the surveillance society as obtrusive, and we cheer when Bourne gets around it. On the other hand, tracking those guys real time was obviously vital and necessary.

What do I make of it myself? I love, love, love the fact that it’s that complex in the Bourne films, it’s not black and white. There are no easy answers to these questions – we need the best intelligence we can have to protect the citizens of a free country. On the other hand, we have to have some boundaries to the intrusions into the lives of free citizens, otherwise it’s no longer a free society. Those two things are in tension, and I don’t have the answer. It’s not my job to provide the answer, because I’m not a politician. But I do tell stories, and the best stories are complex, and I think that’s a complex issue and anybody who pretends it’s simple or one sided is, I think, a demagogue or a propagandist.

When we talked about United 93 we talked a bunch about the theoretical aspects of terrorism, of who is a terrorist and why they use those tactics. What struck me about the Glasgow attack is how all these people were doctors, which doesn’t fit the angry poor person profile.

It’s incredible.

I’m curious what your take on that aspect was.

I’m very reluctant to get into it, and the only reason is because while I’m aware of it, it came at a time when I was literally – I finished this film Thursday night. We were going 18 hours a day, seven days a week. I feel like I don’t want to give a knee-jerk reaction, that I need to get home and read up on it. But it’s clearly a terrible and dreadful thing, very, very troubling.

But I feel very lucky as a filmmaker, because I get to do the films I want to do, and I get to express myself in distinctive ways. I get to go and do United 93, which is obviously about something that I want to explore myself, but then when it’s done, I want to go off and have fun and make a mainstream commercial movie. Having said that, what I love about Bourne is the quality – the interesting thing is to make a good movie in the mainstream. That’s the challenge: can you make a good movie in the mainstream? It seems to me that the danger is that we get ourselves into a state of mind where we say good movies can’t be made in the mainstream, and I don’t accept that or believe it. There are lots of great movies made in the mainstream, of all kinds.

For me, Bourne is front and center about entertainment, fun, with quality. But what’s front and center in the Bourne franchise is that this is a real man in a real world – it’s not a superhero, it’s not CGI, he doesn’t have magical powers, he doesn’t have gadgets. He’s a real guy and you’re on his shoulder with him, seeing him as he processes information, makes choices and executes them. That’s incredibly thrilling and rewarding, and I love it. I think directors like to do their thing. There’s a sort of showman inside every director, because essentially what they’re doing is telling their story and putting it on a screen, whether it’s a small arthouse movie or a big mainstream movie, there’s an element of ‘Come see my show!’ about it. What’s brilliant about a Bourne movie is that it allows me to strut my stuff, but also fight in the mainstream for quality. And I believe in that.

I’ve come to Hollywood later in my career; I’m not a young boy, I’m in my prime. I have a lot of years of good films to go. I didn’t plan to come here, and none of my films I’ve made – you wouldn’t expect that a small film about a massacre in an Irish town 30 years ago would lead to Hollywood! I came to do Supremacy because I liked Bourne Identity – that was what brought me, I didn’t come to just make a generic film – it brought me to have an adventure here, and I thought I would like to see if I could do something good in the mainstream. I had never tried to do it before. And I enjoyed it, and I looked at the film when it was done and thought, ‘Well it looks like one of my films, I’ve enjoyed the process, I’ve been respected, and I fought the fight to have it be a good film’ – along with everybody else, nobody was trying to stop me. Then I thought I needed a rest, I needed to go off and make my kind of film again, and see if I could do one of my sorts of films out here. That led to United 93. When that was done I decided I had to finish that Bourne story – I wanted to know what the end of the story is, apart from the audience! I wanted to have another go at the mighty Wurlitzer, knowing now what I knew, and having done what I had done. And also – I don’t want to come across all altruistic – it’s a smart move too. If you work in the mainstream, you get the ability to do what you want to do in between. But that’s of course very much in my mind; I did United 93 and they were very good to me, Universal, and I was happy to come back and do my bit in the mainstream.

I believe really, really a lot in what’s possible [in Hollywood]. Most people in my experience, all they want is the best possible movie. They’re willing to invest a lot of money to give you the opportunity to find the best movie. This movie for sure. Nobody once – not even once – on this film had a conversation with me about money or resources. Not even the teensiest sense of… you can tell when people are getting anxious. They kept an eye on it, but it never got out of control and Frank [Marshall] and Patrick Crowley are brilliant producers. You’re making a Bourne movie and you’re evolving your story as you go – they’re not airline meals, Bourne movies. You live off the land and find it as you go, and you have a plan but it evolves and changes. That’s OK when you’re making a little movie, but when you’re operating on this scale, it’s a risky endeavor. Literally Thursday night I wanted to tweak something in the mix on reel six. I spent an extra day. We’re literally right to the last moment; this thing is out, however many prints it is, ten days from now.

Bourne, to me, having done two films, proves you can do good films in the mainstream and studios will support you and that actors will give you their best work and the films can be challenging and entertaining and much loved and have that little bit of chili in the mix that you and I might be looking for to show that it smacks of reality. That they can be edgy and stylish and yet go into multiplexes around the world. I’m proud of everybody who worked on the film, and I think it’s a good film – although you’d have a better sense of it than me –but I believe… it’s a mighty art form. I love it, you love it. I went to the cinema to see Shrek 3 with my kids and we loved it.

They’re hard work, they really are. What keeps you going is different from what would animate you on United 93; it’s a commercial endeavor and you’re trying to make it work broadly. What keeps you going is something I’ve only seen once before, on Supremacy, and it’s what a hit feels like.

It feels good.

Of course it feels good, gratifying on a personal level. But I’m old enough to not be swayed by that. It’s good because it gives you opportunities as a filmmaker, and I’m keenly aware of that. But what drives you through is that sound and feel that you get with the big boom. It’s like hearing perfect pitch. You see in the audience, when I snuck into the back of Bourne Supremacy after it came out, you give them what they want and then some, and when they come out there’s that bubble of excitement. You’ve just given a huge amount of people a tremendous amount of pleasure, and shown you can do a good film in the mainstream.

When you do a Bourne movie you have all those days where it just does not work, and you come off set knackered. You’re exhausted and get disheartened – ‘How the fuck are we going to make this film work?’ – and what keeps you going is that dream that you can complete a much loved story in a way that challenges and surprises and exceeds expectations rather than barely meets it. If we’ve done that and proved that you can make contemporary cinema in the mainstream, that cinema in the mainstream doesn’t just have to be the provenance of comic book characters and CGI worlds – although I love those movies too – but that the contemporary world can live in mainstream cinema.

You talk about your films and the mainstream films –

They’re all my films. I don’t see them as not my films, but they’re different instruments. One is the chamber and the other is the full orchestra.

So which one is Imperial Life in the Emerald City going to be?

Good question. We’ve optioned the book Imperial Life in the Emerald City, but the screenplay that Brian Helgeland’s written is much broader than that. It’s basically a film about the Iraq conflict; it’s about what went wrong and why. The answer to your absolutely excellent question is that what I want to do is take the sort of impulses that led to United 93 and play them out on a much bigger scale. Why? Not because I have vanity of scale – I could go and make a big movie tomorrow. It’s because it’s the biggest issue in our world today. As much as I believe that the cinema that I watch and you watch needed to address 9/11, it needs to address Iraq. And that demands scale. I think if you’re going to address that subject credibly, you have to be there. We only go there in soundbites on TV, but we have to be there for two hours and live it and understand it. So it needs scale. And that’s my next challenge: can I, in this environment, make a film like that, and the answer is that so far I’ve only been encouraged down that road.