It’s time for another thrilling edition of Late to the Party, a column title which I have come to realize is not as original as I first thought. There’s some sort of meta-recursive lateness going on behind-the-scenes, here, and it makes my inner ears kinda hurt. Anyway, this here is the introduction to my bi-weekly article mapping those films for which I have very little excuse for not having seen, yet. In the past couple of weeks, I have taken a look at Die Hard and Conan: The Barbarian; today, something a little less in the couch-and-crackers realm. Entirely by accident, it seems I’ve somehow missed…

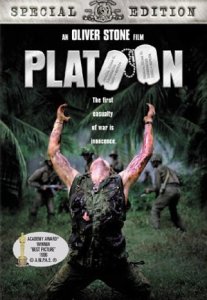

Platoon

I’m not naturally a war-like individual. I was born with a birthmark in the rough shape of "4F" stamp. Were I born tens of thousands of years ago, I would have been a walking endpoint for my own genetic line. I’ve never considered joining the military, harbor a faint and wholly unjustifiable disdain for those who do, and really hate the ad campaigns for all the armed forces. I’m a civilian, through-and-through.

And yet I love war movies. I’ve tried for a few years to come up with a defensible position as to why, but nothing’s come up so far. "Do you just like the emotions?" asks my wife. "Nope," I say. "Gunfights are cool."

"Then are you in it for the blood and bullets?"

"Not a chance. How cold do you think I am?"

"Then put on the headphones because that junk is too damn loud."

I think I am often drawn to the human component of war. Just recently, I was discussing Children of Men with a co-worker (a kindly old Austrian woman who is exactly the kind of senior I want to be when I grow up, except not a woman or Austrian.) She had been entirely absorbed by the film, except for the combat sequences in the refugee camp at the end. Too much violence for her taste, she said. I countered that the brutality was beautiful, and she requested I stay a safe distance away from her patients at all times.

I’m being ever-so-slightly facetious, but I do think that those last scenes of Children of Men are among the most powerfully attractive that I’ve seen in the past few years. (You’d be forgiven for discounting that based on this column’s premise.) There’s a kind of root humanity on display in the middle of street-level conflict, a simplicity and romance that’s hard not to admire, and occasionally envy.

In that regard, it seems to me that war gets displayed in fiction this century and last in a similar light to the one that shone on sailing in the nineteenth century. Not that young men didn’t go off to war full of ideals back before the advent of the Red Baron, but it was the sea that drew the imaginations of novelists. But take a look at the work of some of those novelists who succumbed to their own simple cravings for tall ships; to a man, they defuse the power of the romance. Read some Melville for a great example, particularly the first few chapters of Redburn. Young men get suckered in by their unfounded envy of that other life — be it sailing or combat — and the lucky ones live to warn against it.

Oliver Stone was an soldier in the Vietnam conflict, and his time there informs Platoon with the strength of the disillusioned. I’m going to try as much as possible to remain focused on the fictions, regardless of their basis in history or the experience of our military-minded readers; I can’t presume to know the first damn thing about actual combat situations and wartime relationships.

What I can comment on is how strangely compelling it is to witness a situation stripped of all guile. It’s that simplicity thing again; it’s inherently absorbing to confront scenarios in which all the complications have been reduced to a binary trigger-pull. Violent situations summon violent responses; the people in them lose the shutters that cover their impulses.

That means war fiction is concerned with portraying the bare best and base worst that humanity is capable of; the only cloaks pulled over emotion are those of courage, which are thin covers. The unfortunate result (for the characters, anyway) is that they may discover who their comrades are behind the facades.

Between Willem Defoe and Tom Berenger, Stone created the perfect bed to breed disillusionment. For Charlie Sheen, the progression from point innocent to his personal end has less of the madness of hell his father went through in Apocalypse Now; it’s an earthbound conflict between the two father figures he serves under. What I love about Sheen’s struggle is that it’s not at all about maintaining innocence despite all odds; there’s no doubt his innocence is the "first casualty of war." Defoe’s character possesses none of the ignorance/innocence that traditionally composes half of the good-and-evil dyad. Defoe is not God (despite the frequent Christ references) and Berenger is not the devil.

The question becomes: Where do you go after innocence? Or, to go with the naval theme, where do you go when you make landfall again? Whatever you do, you’re going to have to do it without the help of illusion.

It might get me burned for saying so, but I love the fact that the prime antagonists in Platoon are the Americans themselves. That’s an illusion that we’re all better for having stripped away: that our own group, whatever it may be, is infallible. It’s not so. To get topical, we Americans have had way too many examples in the recent Iraq conflict of how we’re fighting, on an individual level, with ourselves. War fiction is never an outwardly focused endeavor; it’s always a context for violent internal upheaval, wars of succession in the brain.

You could rightly guess from my position on real-world war that I’m kind of a pacifist. At the same time, I get an absurd amount of reward from war movies. How am I supposed to reconcile those positions? I’ve never liked the argument that humanity couldn’t understand good if there was no evil; however, I can argue that putting both in the same place highlights the disparity. Maybe I just love to see how good people can be. That sounds trite and entirely plausible.

I, uh, also love to see people getting their legs blown off. Especially when it’s a young Dr. Cox fumbling a grenade. Go figure.

Come back in two weeks. I promise, you’ll wonder how sometimes I even manage to keep breathing.