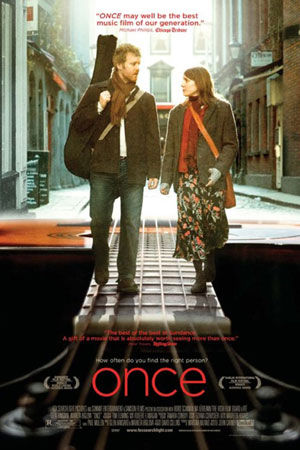

I would have attended the press day for Once no matter what, but the fact that there was going to be a musical performance sealed the deal. Glen Hansard and Markéta Irglová, the stars or Once and real life musical collaborators, came in and did a trio of songs from the film as well as a cover of Van Morrison’s Into the Mystic (which they had wanted to use in the movie, but apparently Van wasn’t playing nice with licensing). Markéta joined Glen on vocals and he played the same impossibly battered guitar that he used in the film. I wish I could have recorded the performance, mainly for myself, but also because I think hearing them play would sell you guys on seeing the movie (to hear some of their songs, visit their MySpace page).

I would have attended the press day for Once no matter what, but the fact that there was going to be a musical performance sealed the deal. Glen Hansard and Markéta Irglová, the stars or Once and real life musical collaborators, came in and did a trio of songs from the film as well as a cover of Van Morrison’s Into the Mystic (which they had wanted to use in the movie, but apparently Van wasn’t playing nice with licensing). Markéta joined Glen on vocals and he played the same impossibly battered guitar that he used in the film. I wish I could have recorded the performance, mainly for myself, but also because I think hearing them play would sell you guys on seeing the movie (to hear some of their songs, visit their MySpace page).

After the performance, Glen and Markéta were joined by John Carney, the director and writer of the film. Glen and John are Irish, so they can talk; Czech Markéta was much more quiet. Their film was one of the hits of Sundance, and it’s poised to be a minor arthouse success (if there’s any justice – seriously, this is one of my favorite movies of the year), but they were taking it all in stride, and John especially came across as a voluble and ingratiating Irishman; I can’t wait to see what he does next.

Once opens this Wednesday. For the love of god, go see it.

Does this film come from your past in music, John?

Carney: I come from a reasonably musical family. My older brother was a music lover and he made it his things to go out and discover weird bands in the 70s and 80s that no one else knew about and brought them home and exposed his younger brothers to this kind of obscure music. We had a piano, and he kept his guitar under the bed and I wasn’t supposed to play it, so I would play it in the middle of the night. Then I met Glen and I joined his band and I played in The Frames for a few years. Then I got bitten by the whole film thing, and I went to seek my fortunes as a film director, which was a weird thing to do in Ireland at the time, since there was no Irish Film Board and it wasn’t state subsidized and there was Jim Sheridan and Neil Jordan and they had their houses up in Dorkey. It was kind of a funny time.

I made a couple of films, and myself and Glen had said we should do something – could I use his songs in a film, or shoot a video in a band, could we have our two artistic endeavours cross together. But it never happened. Then I came up with this idea of a busker and an immigrant in a musical. I wanted to do something that would get this musical thing out of my system. I love music, and I would stop writing scripts to play on the piano for three or four hours; I’d waste three or four hours of my day just playing Billy Joel songs on the piano.

Glen, how did you start?

Hansard: It started very suddenly in that my uncle, who was a very charismatic character – he’s my mother’s brother, and she comes from a family of 13 kids and he was one of the younger brothers. He was this amazing guy, all the girls thought he was good looking and he had great hair. He was kind of a hero of all of ours as young boys, and at one point in our lives he disappears. My mother said, ‘He’s gone away.’ It turned out he had taken a car and driven it across Europe filled with something illegal and gone to prison in Turkey for a couple of years. His guitar got left at our house, and my mother had to keep stopping me from taking it out because it was a nice guitar, a Gibson Hummingbird. Then she thought after a year of slapping my wrist and putting the guitar away that, since my uncle was a huge Leonard Cohen fan, to teach me Bird on a Wire. Then when he comes through the airport, with all the family to greet him, there will be his nephew on the guitar playing a song, like saying he’s been a good influence on the family. That was how it started, I learned to play Bird on a Wire on the guitar. I was about I suppose 9, 10. I went to the airport, he came through the arrivals hall and the first thing he said, ‘What happened to my fuckin’ guitar?’ It had been wrecked. I had been dragging it around the flat. I didn’t have any idea that you keep this thing precious.

But then he took me into his band and I played music with him. But at the same time, my school teacher advised me to leave school at 13 and to become a street musician. He said the best place to start your career is on the bottom rung. I learned to play a few chords from my uncle, but being a street musician was my education.

John, what gave you the confidence that Glen could act?

Carney: I originally wanted Cillian Murphy for the role – I know Cillian, and he can sing. He’s quite a good singer. I thought I’d do the usual thing where you get a good actor who can half sing and train that voice, but then it became clear to everybody on the film that we should do it the other way around, that we should get somebody who could really sing and half act and I’ll trust that I would be able to do something magical with that. I didn’t have to do much – I’ve known Glen for a long time, and directing a non-actor is knowing them and getting to understand their personality and putting them in a situation where they’re comfortable and can bring this character to life.

Glen, what gave you confidence?

Carney: He didn’t have any. He said, ‘If I’m rubbish, just sack me on the first day.’

Hansard: I was terrified, for a few reasons. I didn’t want to suck for [John’s] sake, and I didn’t want to suck for my own. I’m a reasonably confident person behind a guitar, but in front of a camera is a whole other ball game. I needed him to tell me the truth – are we rubbish, are we going to pull it off, is it going to work? Because if it isn’t, let’s just pack it in.

When Cillian pulled out, or whatever happened with Cillian, I suddenly felt that John was just jumping on the nearest person to him, and that if he really wanted me to play this role he would have asked me at the beginning, and maybe I’m the rebound. But then again, at the same time it made a lot of sense – I’m very close to Mara, I’m close to John, so this was something I was doing with me mates. This wasn’t like The Commitments, which was Alan Parker and there were loads of people between you and him – that was a very obscure scenario, which I never felt like I would go back to at all. But with John it was, let’s just do it.

John, how did you approach making a musical?

Carney: In the top ten of my favorite films I would put Guys & Dolls and Singing in the Rain and A Star Is Born. They’re films that, if it’s a Sunday morning and I’m staying in because it’s rainy, I’ll stick in Singing in the Rain or the scene between Marlon Brando and Jean Simmons in Guys & Dolls, just to hear a song. It’s like putting on album, except that you sit back and watch these great scenes. So about ten percent of the great musicals in the world I would rate very highly, while the rest I just hate. I’m not a big musical guy, I kind of like certain ones. I wanted to make a modern day musical, but how do you do that? How will you make a younger audience that doesn’t like people breaking into song sit back and watch a film and leave it having watched eight or nine songs in their entirety. It quickly became clear to me that the tools would be that I would shoot it on tape, I would use non-actors and I would make it a small little story. The story was really secondary, in a way, to the tone of the project. It was always something I wanted to do and make a film where you leave the cinema not aware that you watched all those songs; it didn’t feel like, ‘Aw, here’s another song.’

Can you guys talk about the relationship between the script and the songs, how they evolved?

Carney: It was a very collaborative process. I liked being able to work with the songwriter of the musical. In the classic musicals, the songs were already there, and you couldn’t really touch it and you wrote a story around these songs. I liked that I knew Glen and I could communicate with him and say, what do you think about this as a theme, and he would mull it over and come back with a lyric or a title, or with a song that he had written ages ago. It was very much a song here, a scene here, and we would bounce off ideas with the skeleton of the story in place – guy meets girl, he’s broken hearted, she’s this, they come together.

Hansard: John would say, ‘I need a song called. Once,’ or ‘I need a song for when Mara walks down the street, and it’s the only part of the film where we’ll suspend reality and I’m going to hire a crane it’s going to cost five grand so we better get it fuckin’ right. Mara’s going to walk down the street and we’re going to have a musical moment so we need a song that’s very strong and has a beat.’ Things like that, where we were acting during the day and at night time going back to the flat where we were staying and picking up a guitar and saying, ‘OK, he needs a song like this.’ It was a very creative time, we’d finish in the evening and then pick up the guitars and work on the songs.

How different is the music in your head from the music that you do with your band?

Hansard: The beauty of it is that they’re the same. Some of the songs that are in the film are actually on the Frames record. I just wrote a bunch of songs, which is what I do, and then for the film John wanted specific songs, which is what I do. John has made the point before that if someone doesn’t like the film, it’s probably because they don’t like the songs. And that’s cool. John says, ‘That gets me off the hook!’

Carney: But that’s how a musical should be at the end of the day, isn’t it? The only musicals I hate are the ones where I hate the music.

Markéta, how do you know them?

Irglová: I met Glen first, about five or six years ago. He came over with his band, The Frames, to my country, and my dad was helping the band with the gig. We had a party at my house and sang songs around the fire, and Glen found out I could sing and play the piano; the next day they had a gig and he got me up on stage to sing a song with them, and that was the beginning of whatever musical relationship we have together. We’ve been playing together ever since. I met John two or three years ago; I knew his last film, so I knew who he was, then Glen called me up and told me about this project and would I be interested in doing it.

Are you planning on doing a solo album?

Carney: That’s a great idea!

Irglová: I do write songs, and the idea of making an album is nice, but that being said, my songs are down – they’re depressing! I don’t know even know if I want to go on with a career as a musician, but I would love the idea of the album being there as a document of this period of my life, so I could I say I did that, but I just haven’t had enough time. I’m still in school, by the way, so I’m doing a lot of things at the same time.

Carney: It’s so great working with Mara because she’s so unlike other actors – I love working with people who are going to give you their all in a film and it’s not just for their reel and they’re not going to do another film another month afterwards. I like the idea of a film set being like a family, where you’re involved in something really intense. And I like that they’re both non-actors because that means I’ve got them forever and they’ll never do anything other than my film!

Hansard: For me it’s beautiful – whatever else happens, John has documented a time in me and Mara’s history and the music I’ve written. In a few years I can show it to my kids and say, ‘Hey, your dad was in a film years ago.’ That’s the beauty of it, that’s the moment that’s more important than all the rest of it. At the end of the day, when all this evaporates, when all the ink is dry, hopefully in twenty years the film will have aged well and I can take it off the shelf and tell my kids, ‘There’s your dad when he looked good and had hair.’

John, was there ever a point when you wished you had shot on a higher grade video or on film?

Carney: It’s different tools for different stories. Every young filmmaker – some people call me a young filmmaker, and I love it – every young filmmaker wants to shoot on 35, and it’s ridiculous in some ways because you’re going to spend all your money on 35 and you’re going to bring the circus into town with buses and cables and all that stuff. There are some stories that need different approaches. This is a very intimate project, and the feeling that you shouldn’t be watching what you’re watching is part of the story. The footage of the woman Glen watches on the lap top, that’s my girlfriend, and that’s footage of seven years of our relationship with all the rude bits cut out. I wanted the film to feel intimate, and it is a film that friends made – we made it to be with friends, not to be here promoting it, and everything else that has happened has been a bonus. And DV was always the way to make it for that reason – to keep it cheap.

Hansard: Plus because me and Mara aren’t actors, there was a lot of footage that needed to be shot to get us right, and if you were doing it on film it would cost quite a lot. I was all about doing it as a black and white 16mm.

Carney: There’s no point in being beautiful for this film – let the music and the performances be beautiful.