Batman #0, Batman and Robin #0 and Frankenstein #0 (DC, $2.99 – $3.99)

By Graig Kent

I wasn’t planning on picking up any “Zero” titles from DC this month. After the onslaught of the New 52 over the past year I really though I could use a break, and the fact that the stories this month in a sense would be stand-alone, quasi-origin stories, taking part outside of whatever ongoing plots were taking place in each series seemed as ideal a time as any. Of course, that thought was a fallacy. Slap Grant Morrison’s name on a book and I’m going to buy it, so Action Comics #0 was a must, so there was the first exception that broke open the floodgates.

I am trying to break myself of my completist tendencies, but Batman #0, with both series writer Scott Snyder and Greg Capullo on board, made it hard to justify omitting from the series run. I didn’t need another Batman Origin Story, and thankfully Snyder and Capullo didn’t deliver one. What they did deliver was a Batman tale that seemed, in part at least, inspired by the Christopher Nolan Bat-universe. Taking place early in Batman’s career (in fact pre-Batman, but post-Bruce Wayne sabbatical), Bruce has infiltrated the Red Hood Five, a quintet of homicidal bank robbers. It doesn’t go well. People die. Bruce is almost killed, The police get involved. Bruce barely escapes with his life (on a bike reminiscent of the Batpod). He and Alfred have set up shop not in a cave under Wayne Manor, but in a place not unlike from the bunker in The Dark Knight where the duo are still building the Batman and his infrastructure. A visit from Lieutenant Gordon puts on display their relationship, simultaneously awkward yet comfortable in its early stages. As happy as I was to see Scott Snyder be able to carry on his pre-New 52 Batman storytelling into post-New 52 Batman stories without much interference, still a part of me thinks that perhaps really starting from scratch with Bruce — as Grant Morrison is doing with Clark Kent in Action Comics, showing the birth of the hero, rather than the established hero — would have been the better way to go, with Snyder at the helm. Snyder here continues to prove that he has as solid a handle on the Bat-universe as any writer, and he will no doubt go down as one of the greats, and if Capullo hangs on for even half as long as he did on Spawn he will doubtlessly be one of the premiere Bat-illustrators of all time.

As much as Snyder’s lead story validated my purchase, it was writer James Tynion IV’s back-up story that was the reward, a deceptively simple story that in one fell swoop establishes the origin story for the Batsignal, affirms the relationship between Gordon and Batman, establishes many corners of Gotham and the city’s need for vigilantes, and plants the seed for Barbara Gordon, Tim Drake, Dick Grayson and Jason Todd all to become part of Batman’s entourage. Tynion’s 8-page story gives 2 pages to each character, all Paul Thomas Anderson-style connected thematically/emotionally without being intertwined… all that’s missing is an Aimee Mann soundtrack. It’s a flat out brilliant 8-pages of myth building, and Tynion is able to do more with each character in 2 pages than what some writers are capable of doing with them on entire runs. I’m unfamiliar with Tynion’s work previously but if this is a sample of what he’s capable of, he’s got superstar written all over him.

As much as Snyder’s lead story validated my purchase, it was writer James Tynion IV’s back-up story that was the reward, a deceptively simple story that in one fell swoop establishes the origin story for the Batsignal, affirms the relationship between Gordon and Batman, establishes many corners of Gotham and the city’s need for vigilantes, and plants the seed for Barbara Gordon, Tim Drake, Dick Grayson and Jason Todd all to become part of Batman’s entourage. Tynion’s 8-page story gives 2 pages to each character, all Paul Thomas Anderson-style connected thematically/emotionally without being intertwined… all that’s missing is an Aimee Mann soundtrack. It’s a flat out brilliant 8-pages of myth building, and Tynion is able to do more with each character in 2 pages than what some writers are capable of doing with them on entire runs. I’m unfamiliar with Tynion’s work previously but if this is a sample of what he’s capable of, he’s got superstar written all over him.

If you thought a Bat-sidekick was missing from Tynion’s bunch, that’s because Damian’s path to sidekickery a) doesn’t fit in the same way Babs, Tim, Dick and Jason’s do and b) is instead told in Batman and Robin #0. I have to admit that when Grant Morrison introduced Damian (a half dozen years ago now!) into the Bat-universe proper, I hated the little shit, both conceptually and story-wise. Eventually I did get his purpose, giving Bruce an heir and a sidekick that served to challenge the status quo, not just of the Bat-books at the time, but of the whole concept of what a “sidekick” is and what the Batman and Robin dynamic should be. Through Morrison’s run on the original, pre-New 52 Batman and Robin he actually became a draw for me, a character whose motivations interested me and whose lack of humour and self-awareness are actually quite endearing when pitted against the other supporting Bat-cast like Alfred and the formerly-Robins.

This zero issue serves as explanation as to how this de-aged Batman, who only appeared on the scene roughly “six years ago” (in “current” DCU continuity, whatever that means), can have a 10-year-old son, something that had been answered previously, and briefly in dialogue in one of the Bat-books of the last year (I’ll hazard a guess it was Morrison’s call in a recent Batman Incorporated). Moreover Batman and Robin series writer Peter Tomasi uses it to show, albeit somewhat briefly, exactly what kind of mother Talia Al Ghul was to her son, and what sort of trials she put him through to make him the dead-eyed, cold-blooded, remorseless bastard we’ve all come to know and love. Tomasi does skillfully weave in Damian’s curiosity about his father as a driving motivator to his character, which goes a long way in defining him as we’ve seen him to date. It’s a bit of a breezy tale that is told more visually than with words, virtually a 20-page montage, but it’s a definite showcase for Pat Gleason who has fulfilled his promise as an artist, and more importantly a storyteller since his early days on Image’s Noble Causes a decade ago. He handles action scenes with a technical precision, masterful orchestration, while handling the emotional component of the story with equal, if not more skill. His toddler Damian could still use a little refinement, but even compared to the beginning of his run with Tomasi on Batman and Robin, his illustrations of children has strengthened immeasurably.

Batman and Robin #0 could be considered the origin of a monster, and while Frankenstein: Agent of S.H.A.D.E #0 does  delve into the monster’s origin, it’s more the tale of the humanity inside the monster. Matt Kindt distills the character’s birth into a scant three pages, but they’re very effective in establishing this world’s Victor Frankenstein as the monster in human guise and ultimately pitting the creature and his maker against one another to show exactly how different they are. Narrated from the perspective of S.H.A.D.E’s Father Time, there’s a full assessment of Frankenstein, the mad doctor and hints at the longevity of S.H.A.D.E as a secret organization. Kindt delves into Frank’s emotional core in this one and, for the first time since he took over the series from Jeff Lemire on issue 9, just what kind of grasp he has on the character. It’s safe to say that Frankenstein is truly his now.

delve into the monster’s origin, it’s more the tale of the humanity inside the monster. Matt Kindt distills the character’s birth into a scant three pages, but they’re very effective in establishing this world’s Victor Frankenstein as the monster in human guise and ultimately pitting the creature and his maker against one another to show exactly how different they are. Narrated from the perspective of S.H.A.D.E’s Father Time, there’s a full assessment of Frankenstein, the mad doctor and hints at the longevity of S.H.A.D.E as a secret organization. Kindt delves into Frank’s emotional core in this one and, for the first time since he took over the series from Jeff Lemire on issue 9, just what kind of grasp he has on the character. It’s safe to say that Frankenstein is truly his now.

I have been up and down on Alberto Ponticelli’s work since the beginning of the series. I wasn’t a fan at first, the lines were rough and uneven, and the work just seemed sloppy, but by issue #6 I recognized the stylistic choices that Ponticelli had made, that it was no reflection on his abilities as a draughtsman or artist, and it had grown on me. Then they brought in an inker (Ponticelli had been inking his own work to start), and it definitely changed his style, reducing the amount of lines busying up the page, but also stealing away much of those very same stylistic choices he was making as an artist. Somewhere in the month between issue #12 and this zero issue, inker Wayne Faucher has learned how to stop fighting against Ponticelli’s style and instead work with it. No longer is the inker attempting to clean up Ponticelli’s designs, but now he’s genuinely embellishing his work, and the first page is a macabre glory to behold while the second page is a visual feast of arcane turn-of-the-(20th)-century super-science and fantastic technology. This is probably the best the book has looked all series.

Overall, given the quality of these books, particularly as done-in-one books, the zero issues may actually be a high point of the New 52 so far, a genuinely accessible starting point for new readers to hop on in a manner the new #1s didn’t quite manage to accomplish en masse.

All three: Rating: Out of a Possible 5 Stars

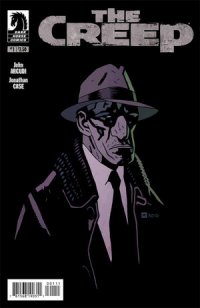

The Creep #1 ($3.50, Dark Horse)

The Creep #1 ($3.50, Dark Horse)

by D.S. Randlett (@dsrandlett)

I gave the “zero issue” of this series a rave review a while back, and nothing’s really changed. One has to wonder why the issues are numbered the way that they are, as this feels like a definite second issue. Not that it should matter, because you really should have read The Creep #0. And if you haven’t, get on it. I know that it’s usually proper critic decorum to save the evaluation of a given work until the last paragraph, but I feel like this simply needs to be said: The Creep, two issues in, might be the single best comic book in existence right now. Why does this out of left field suburban noir from a couple of non A-list creators merit such praise? For one, it’s everything that the book does differently that sets it apart. For many decades comic books have relied on a sense of momentum. Grant Morrison’s book Supergods has a great section about Action Comics #1. In context, he’s talking about the effect of Superman on pop culture, but Superman brought with him a narrative style that changed the way we read comic books. This was a character that moved with great speed, and Siegel and Schuster constructed their storytelling to keep up with him. Reading that section, it hit me that this sense of superhuman movement has seeped its way into the way comic books tell most stories. Anymore, it’s just how comic books work. There are exceptions, of course, but the “need for speed” has become so ingrained into the comic book creator’s lexicon that many who seek to hit different emotional notes than the need for story momentum allows for often end up meeting it halfway instead of fully liberating themselves from it. The Creep has managed to break free of this speed trap, and it does so through an emphasis on its main character, Oxel. It’s a rare thing in a detective story to have the detective truly be the center of the story. I know that it’s an old saw that in mystery fiction, that what the investigator is truly investigating is him or her self. But mystery writers very rarely pull that off successfully. Character in comic books is often told and not shown (thought bubbles, narration boxes, etc.), but Arcudi’s script for The Creep eschews such mechanisms and allows the comic book format to explore character in a way that I haven’t ever quite seen before. There’s a scene in The Creep #1 that takes place on the Manhattan subway that’s more reminiscent of a show like Louie than any comic book. Oxel is riding the train to his apartment, and thinking about his case, and finds himself staring at a young gay man who takes offense. We’ve all been here in some respect, lost in thought and unknowingly staring at somebody in a way that creeps them out. The way Arcudi and artist Jonathan Case render this scene is very naturalistic, and it lets all parties involved express themselves. There’s a clarity of character here that’s rare in any medium, and it comes through the willful sacrifice of “comic book momentum.” There are some pretty heavy themes at play. The most obvious is the effects of suicide on families and the people that they know, but this is a nascent idea as far as the book’s concerned at this point, and will be more developed in time. Possibly more interesting is the series’ exploration of Oxel’s outsider status. He suffers from a disease called Acromegaly (Arcudi has gone on record saying that he based Oxel on Rondo Hatton), and it shows. He’s rather monstrous, and it would seem quite weak. The story involves an old flame from before Oxel was stricken with the disease whose son has committed suicide, and her mere calling upon him reminds Oxel of his old life. The story is just as much about Oxel finally coming to terms with the end of his old life as it is “solving” his ex’s son’s suicide, and in a way Oxel is in the perfect place to understand the suicide. After all, the beginning of his deformity represents a sort of death. He’s passed through the curtain, in a way, and it lends the story an interesting perspective. Just read it already.

Rating: Out of a Possible 5 Stars

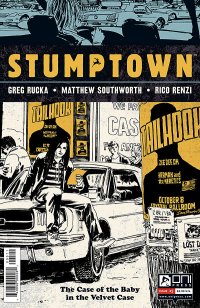

Stumptown Volume 2, #1 (Oni Press, $3.99)

by Graig Kent

It’s been exactly 2 years since the first Stumptown mini-series folded, and while I can’t say I’ve missed it nor felt any recurring sense of longing for the series, I’m delighted to see it back on the stands. Greg Rucka is one of the preeminent writer of female characters in comics today, most notably with Queen and Country and Batwoman. While his Portland-based private detective Dex Parios may not be as immediate a character as Tara Chace, or as striking as Kate Kane, she’s uniquely her own from frame one, and this first issue of the second volume of the series establishes her perfectly whether you’re new or being reintroduced.

Stumptown is one of Portland’s nicknames, and if, like me, your primary exposure to Oregon’s largest city is the comically exaggerated one found in Fred Armisen and Carrie Brownstein’s sketch program Portlandia, then you may be surprised to find the city in the comic is still somewhat familiar (or perhaps not). There’s a definite vibe that Portland seems to give off, and while Portlandia takes it to hilarious extremes, Rucka scales it back to everyday levels, perhaps with a drizzle more of darkness.

The case Dex finds herself involved in this series (“The Case of the Baby in the Velvet Case”) seems a simple one, as the lead guitarist of a famous (and fictional) Portland band hires her to find a missing beloved guitar. Like any great detective series, the case isn’t all it appears to be, and more players start piling into the situation, including a gang of skinheads and federal agents. This is more T.V.-style detective series than cinema-style detective series, but I think that’s by plan, making it more accessible, requiring less cleverness, if you will, and more solid storytelling and characterization.

I was left impressed with Matthew Southworth’s work after the first volume, which I recall being bold with his line weight and not afraid of shadows, but not ala Mignola, nor any attempt to push Stumptown into noir stylings. Instead, alongside a superb attention to detail (just check out that car Dex sits on on the cover) Southworth brought Portland to life in the pages. He does so again here, but this time his work is more open, with the lines much looser and the shading being left to the colorist. Unfortunately the best description of Rico Renzi’s colors I can come up with is muddy. I don’t know if there was a printing error but the colors make the pages look fuzzy or washed out and generally unappealing to look at. It’s a shame because in black-and-white or duo-tone (like on the cover) I think Southworth’s work is incredible.

Rating: Out of a Possible 5 Stars

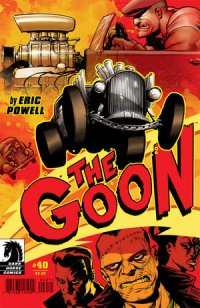

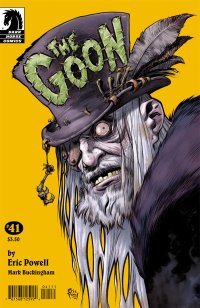

The Goon #40-41 (Dark Horse, $3.50)

The Goon #40-41 (Dark Horse, $3.50)

By Adam Prosser

The Goon’s been away, more or less, for a while now. Sure, there have been a handful of issues, but since “Goon Year”—in which creator Eric Powell published an issue a month along with the standalone graphic novel “Chinatown and the Mystery of Mr. Wicker”—things have been quiet on the Goon front, with only a handful of issues in several years. But lately things have picked up for the series, and these latest two issues, published relatively close together, seem to indicate that the series is picking up steam again.

They also provide an interesting representative sample of what the series has evolved into. The Goon used to be an absolutely hilarious comic, possibly the funniest on the stands, and also carried with it a sense of endless, reckless invention. The Goon’s world was one in which anything could happen, and usually would, in as surreal and violent a way possible. However, something’s happened to the series that’s happened to a lot of comics: it found its niche and started focusing more on the most prominent elements and characters. The series was still frequently bizarre and insane, but it had a more specific, and often more serious, story to tell. As a result, the comic started to become easier to pin down, which isn’t a bad thing, per se, but it has led to something of a change in tone; stylistically, the book’s tilted away from “Warner Brothers cartoon” and more towards “EC Comic”.

Or at least, it had. Some of the recent issues have been pretty berserk, to be sure, like issue #39’s satire of the superhero industry…but that issue landed with a bit of a thud for me, since most of the points being made were pretty obvious. I’m happy to report, however, that issue #40 was one of the funniest and most “classic” Goon issues we’ve seen in years, telling a tale of Goon and Frankie’s younger days, when they took advantage of a brief Prohibition in their nameless town (rather reminiscent of that Simpsons episode) to become moonshiners and rum-runners. This leads, somehow, to a series of drag races, one against a rival hillbilly clan and another against a mutant swamp ape, with art for the latter clearly inspired by Ed “Big Daddy” Roth. The issue shows the book returning to its roots as a book for Powell to experiment like crazy and appropriate from whatever artist or cultural influence he feels like that particular week.

And then, abruptly, the next issue veers right back into “Goon Year” territory, with what’s possibly the most “Tales from the  Crypt”-esque issue Powell’s done yet. We hear a series of stories, many of them condensed into a page or two, from The Nameless Man, The Zombie Priest, currently down on his luck, living in the gutter, and forced to subsist on minor acts of hedge magic (which always rebound horrifically on the customers, of course). The contrast between this issue and the last really highlighted what’s changed about Powell’s work for me: there’s a real sense of anger running throughout some issues now. During Goon Year that mostly meant the series’ tragic, film-noir elements came to the fore, with discussions of the Goon’s doomed destiny and the way his town destroys everyone who lives there, but lately it’s seemingly driven more by real-world events; issue #37, in particular, functioned as a paean to unions and a middle finger aimed at rapacious capitalism, and there’s a sequence in this issue that’s even more overt about it. That’s not to say the book has become politically preachy, or even political at all in any overt way, but it’s clearly being affected by what’s on Powell’s mind right now. Which makes sense, really: this book was always a brain-dump by a fantastically created talent. It’s hardly surprising that he’d want to use it to give us a piece of his mind.

Crypt”-esque issue Powell’s done yet. We hear a series of stories, many of them condensed into a page or two, from The Nameless Man, The Zombie Priest, currently down on his luck, living in the gutter, and forced to subsist on minor acts of hedge magic (which always rebound horrifically on the customers, of course). The contrast between this issue and the last really highlighted what’s changed about Powell’s work for me: there’s a real sense of anger running throughout some issues now. During Goon Year that mostly meant the series’ tragic, film-noir elements came to the fore, with discussions of the Goon’s doomed destiny and the way his town destroys everyone who lives there, but lately it’s seemingly driven more by real-world events; issue #37, in particular, functioned as a paean to unions and a middle finger aimed at rapacious capitalism, and there’s a sequence in this issue that’s even more overt about it. That’s not to say the book has become politically preachy, or even political at all in any overt way, but it’s clearly being affected by what’s on Powell’s mind right now. Which makes sense, really: this book was always a brain-dump by a fantastically created talent. It’s hardly surprising that he’d want to use it to give us a piece of his mind.

Issue #40: Rating: Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Issue #41: Rating: Out of a Possible 5 Stars

The Massive #4 [Dark Horse, $3.50]

The Massive #4 [Dark Horse, $3.50]

by Graig Kent

I keep thinking I should be bored with The Massive, except when I’m reading it. The series started with the premise of a world that has gone Topsy-turvy since “The Crash” happened (as rapid succession of natural events that destabilized the entire global infrastructure), centering on an environmental organization called Ninth Wave and their flagship the Kapital and its key crew members. The maguffin of the series is The Massive, another Ninth Wave ship that has gone missing, but over the past four issues, the crew of the Kapital don’t seem all that put out by its loss. Oh, they’re looking for it, but there’s no real sense of urgency to the quest, especially when they keep diverging to places like Hong Kong and Somalia. Action is on the menu, but it buried on there, between salads and soups. It’s not writer Brian Wood’s top priority. Without strong action set pieces, what does Wood use to draw in his reader? World building and character development? Well, yes, actually, and it’s something he’s damn good at.

The world building in the series, is what I’m most impressed with. Wood has decimated the planet, but not in simplified form, like your typical zombie apocalypse or whathaveyou. Instead Wood approaches the new world order from all angles, looking at commerce and borders, technology and infrastructure, governments and organized crime and many other strands that form the complex web of global society. Wood isn’t interested in a simplified world, he wants this new world to be as complex to navigate as the old one. Through the book’s central story as well as keenly designed and deftly orchestrated backmatter Wood really weaves a post-apocalyptic society that never actually went through an apocalypse. It may wind up a total Libertarian fantasy, but we’re only four issues deep so far, so I guess we’ll see.

Rating: Out of a Possible 5 Stars