X-O Manowar #1 (Valiant, $3.99)

by Graig Kent

I’m old. It doesn’t seem that long ago to me (20 years!) that I was picking up the first issue of X-O Manowar the first time around (20 years ago!)… and not just X-O, but Harbinger, Magnus Robot Fighter, Eternal Warrior, Archer and Armstrong, and the rest of the line (20 years ago!). I wasn’t a fanatic, but I had series that I liked and followed monthly, and others I would occasionally pick up (usually involving a guest star from one of the books I was collecting… this was 20 years ago). Valiant emerged at the same time as Image (20 years ago), in a time when the pictures were the main draw to a comic, specifically flashy and hyper-stylized art, and artists like Rob Liefeld, Jim Lee and Todd McFarlane were becoming ridiculous rock star-like celebrities within the industry (20 years ago!). Valiant’s take was different (20 years ago), focused more on story, and a house-style of staid art that serviced the story instead of overshadowing it. At a time when Spawn and X-Men and the Death of Superman were selling millions copies an issue (20 years ago!) and collectors started flooding the markets after news reports of the value of comic as collectibles (also 20 years ago) , Valiant, despite its lackluster art and unrecognizable characters, managed to draw in the collector with a series of innovative variant covers and customer incentives, as well as establish a connection with the fans in a pre-internet age by trying to invest them directly in their new universe, just one of many that popped up at that time (20 YEARS AGO!). Valiant’s goal was to make collectible comics that were also worth reading before being bagged and boarded and long-box stowed. They succeeded, for a time.

As we know, and us old-timers continue to discuss ad nauseum, the market bottomed out. New universes floundered and collapsed in on themselves quickly. Valiant, to its credit, was one of the last to go. After a Hail Mary throw from the video game publisher Acclaim (which didn’t totally air ball but certainly didn’t make the basket) attempting to invigorate the line with hot writers like Garth Ennis, video game tie-ins, Magic: The Gathering licensed books, and a few critically adored series like Quantum and Woody, Valiant and its characters folded for good in 1999.

Just like in the stories, comic characters never die, they just get reborn over and over again. As long as there’s potential to make a buck (no matter how proven some properties are at doing little else but lose money) no comic character will stay dormant for too long. So, like the proverbial phoenix from the ashes, 20 years later (20 YEARS!) Valiant is reborn, starting with X-O Manowar.

X-O is perhaps not the most recognizable concept from the Valiant line (I struggle to think what might actually be their most recognizable concept), but it’s the easiest to market, the simplest of set-ups and probably their most charming concept: think of a barbarian finding a suit of alien battle armor, Conan meets Iron Man.

The first issue – relaunching the series, the character, the universe and the line – comes to us from the creator of the Surrogates, Robert Venditti and long-time Conan artist Cary Nord. If you’re familiar with either of their works, it’s an appealing combination when put beside the pitch. The end result is a well written, nicely illustrated book that unfortunately present only a portion of the origin story of Aric the Visigoth, as he an his band of Roman-opposing warriors are abducted aboard the spider-aliens vessel. To what end? Unknown, but these hard warriors are not going to be defeated and enslaved so easily.

While the book is freely accessible, violent but not gratuitously so, and charmingly straightforward, it’s frustratingly slight for the four-dollar price tag. I think only with certain characters, like a Spider-Man or Superman, can you drag out a revised origin story over multiple months where it’s the differences in the little details that make it fresh. At this stage, most comic book series which choose to use their first issue or story arc to introduce the character at their beginnings need to do so by getting to the payoff immediately. You can’t tease at this point, especially not given the expense of comics and the investment the reader has to make. Double it up. Present the first 40 pages in an over-sized #1 and make sure you get to the money shot. It’s alluded that Aric is going to take the spider-aliens’ technology from the and shove it up the Roman’s b-holes, but we need him to get his hands on that tech and see what he’s actually able to do with it. For all the good Venditti has done in establishing the story (and it’s very well paced), it’s lacking the payoff an inaugural book like this needs.

Meanwhile, as a former reader of Valiant, and having re-read much of my collection in recent years, I can say that the old books don’t hold up so well. They’re not terrible but they lack a lot of pinache and feel pretty dated. Like a higher-budget remake of a film that was good for its time, X-O Manowar shows its deserving of re-treatment, but at the same time, as a former reader it feels like it sticks closely enough to the story of old that deja vu is everpresent. I should clarify that it doesn’t necessarily seem aimed at the reader of old, but instead new readers, however, demographics have shown that the bulk of the superhero comic buyers are people who would have been there the first time around, so I kind of wonder what the point is. That said, origin stories are so tedious and cliche that it is what comes after that will really measure the success of the relaunch and whether it’s worthy of your time (and money). I find it hard to recommend as is, but it just may be worth a closer look in trade.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Dial H ($2.99, DC)

Dial H ($2.99, DC)

by D. S. Randlett

I love China Mieville. His work usually isn’t perfect, but it’s almost always ambitious, almost always honest. Most know him for Perdido Street Station, which is probably his most “typical” book in terms of its narrative, but it still remains an impressive feat of world building. His follow up, The Scar, is one of my favorite genre novels. It took what made Perdido Street Station so refreshing and added a sense of intimacy with its characters and focus in its narrative that is unusual in fantasy, as well as a very strong thematic throughline that is perhaps more unusual in the genre still. Mieville has established himself as not only an imaginative maestro of new worlds, but also as a writer with something to say about the world. His fantasies, when at their best, seek not to provide an escape for the reader, but rather a means of engaging.

Mieville’s flirted with comic books for a some time now, being in talks to pen Swamp Thing at one point. There was also a rather intriguing rejected pitch that he did for Marvel called Scrap Iron Man, about a group of people who have been laid off from a Stark Industries plant who use their knowhow to create the first unionized superhero: Scrap Iron Man. The series was rejected, likely because Iron Man was rising to the height of his popularity at the time, and it just wouldn’t do to have Tony Stark presented as a villain, much less a one percenter. What was so exciting about that pitch to me wasn’t so much the inversion of the Iron Man concept, but the fact that Mieville seemed to be a talented writer who was going to stick to his point of view. Point of view, whether it’s from a Marxist like Mieville or anyone else, laid at the heart of superheroes for quite some time. When the time comes to cross pollinate with other media, though, point of view in superhero comics is usually an early casualty.

All the same, Mieville’s first foray into ongoing comics is here. Luckily, the corner he’s staking out in the new DCU seems to be very much his own. For one, Mieville’s imagination is obviously intact, and the Dial H concept is perfect for him. Fans of Mieville’s Bas-Lag cycle will be familiar his ability to dream up with new forms for consciousness to inhabit, and the first new superhero that we see in this series is very reminiscent of that aesthetic: Boy Chimney is a manifestation of smog belching murder, and the rendition by the book’s artist, Mateus Santolouco is pure nightmare fuel. Later in the book, there’s a superhero whose power is to make people relive their saddest memories and collapse in sobbing heaps. Part of the appeal of the original Dial H for Hero was seeing what random heroes we’d be presented with, and Mieville gets that.

The story itself is rather good. The Dial H concept is classic Z-list DC fare. In the original we had a teenager named Robby Reed who would use the magical H-dial to turn into a random hero to stop whatever Crisis threatened Littleville, Colorado. Here, the concept is much the same, and we’re still in Littleville, but that’s about where the similarities end, and where Mieville’s point of view comes in.

Our protagonist is a man named Nelson, and he’s no longer at the top of his game. Neither is Littleville. Nelson, as we find out in the book’s opening had a job once, a wife once, athletic ability once, and an inner life once. This is mirrored in Littleville, which has the look of a Middle American city that’s gone bust. Nelson himself is now obese, and from the looks of it a several pack a day habit. Instead of getting his life back together, he’s determined that what he needs is “a little distraction.” When he witnesses one of his friends being attacked, he escapes into a payphone and frantically dials 911. Except that isn’t what he dials. The wrong number ends up turning him into the aforementioned Boy Chimney.

Nelson is the direst sort of person that you hear about on the news in America: obese and poor. Mieville seems to be using him to explore his interest in class warfare concepts. Instead of the socialist populism flirted with in the first issues of Grant Morrison’s Action Comics run, Mieville is dealing with ideas of alienation and the coping mechanisms that American culture has invented to deal with it. It’s not an inherently political theme, but Mieville puts it in a class context that’s hard to ignore. Mieville’s far from preachy in his themes, but they do give the story some much needed teeth and intelligence. For those uninterested in such discourse, worry not. The story functions quite well simply as a yarn, but those looking for more will be well satisfied.

The art by Mateus Santaluoco takes some getting used to, but it’s worth it. At first I was a bit put off by the way the faces were drawn, but was soon won over by the rendering of the stories more outlandish elements. Santaluoco also effectively captures the confusion of Nelson’s changes. Instead of heroic and awesome, these events feel perverse and scary. It’s an inversion of the classic superhero. There, the transformation is an expression of the profoundest self, here it’s an invasion and a violation.

Dial H is a solid new entry in the New 52 canon. The Horror/Superhero segment of the DCU has been on a roll, and this is no exception.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

FURY MAX #1 (Marvel, $3.99)

By Jeb D.

Last week, I was tweaking Marvel’s decision to align the Nick Fury of the Marvel Universe with Sam Jackson’s film portrayal, opining that this would clear the way for Garth Ennis to bring back the hard-drinking, hard-living, foul-mouthed bastard he and Darick Robertson introduced into Marvel Knights/MAX continuity (if such a thing exists), and that he later deployed to good effect in the Punisher MAX series. Well, Ennis is back, Punisher artist Goran Parlov is back, Fury is back, and… it may not be quite what readers were expecting.

The year is 1954. Nick Fury has been ousted from active military service for insubordination (whoda thunk?), though of course he (and we) know that’s just a cover for his penchant for uncomfortable truth-telling. Now CIA station chief, in a sidewalk cafe in French Indo-China (what will later be known as Vietnam), he indoctrinates a fresh-faced young CIA officer into the perilous situation of the undermanned French forces. The moral difficulty presented by their purpose in Indochina being that of occupation is a problem for the diplomats, not Fury: he goes where he’s sent, and does his job. Along the way, there are weasly bureaucrats, ass-covering officers, a seriously dangerous femme fatale… and soldiers.

Ennis’ respect for the professional who puts his ass on the line for someone else’s agenda is profound: just like, say, Richard Sharpe, Ennis’ Fury occupies the line that separates the real fighting man from the privileged dandy who thinks nothing of sending men into situations where he wouldn’t be caught dead (so to speak) himself. Fury doesn’t hold the French soldiers responsible for the questionable decisions that put them in the line of fire. Ennis does a particularly good job of showing us where that perspective comes from: the comic is introduced by a montage sequence with a present-day Fury, bottle in hand, grimly relating the tale with an air of bitter cynicism: this book is clearly going to be about how a war hero begins to question the methods and motivations behind the decisions that turned him loose on what were presumed to be his country’s enemies.

If all this sounds a bit sober and didactic for the opening salvo of the latest Ennis MAX outing… well, it is. Ennis can’t help but be informed by more than a half century of fallout from Western imperialism in Southeast Asia, but his history lesson is never glib or overly modern, and the attitudes and perspectives with which he paints the characters and setting ring true. The shadings he brings to the post-WW2 Fury, only just beginning to sense what a lifetime of duplicitous service will mean, are carried off with an easy expertise that few of Ennis’ contemporaries could hope to match.

Parlov’s work with Ennis is always capable, never flashy, and with the help of Lee Loughridge’s coloring, he brings a touch of Milt Caniff to the setting.

If you were hoping for ‘splode and savagery from the latest Fury MAX series, you might have to wait an issue or two; if you want to read a comic that has sharp dialogue, a strong sense of history, and intelligent observations about the nature of warfare in its Coldest guise, you can dive right in.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Smallville: Season 11 #1 (DC, $3.99)

Smallville: Season 11 #1 (DC, $3.99)

by Graig Kent

For the longest time I wanted nothing to do with Smallville. I’m sure there are many longtime comic geeks like me who felt exactly the same. A teen-skewing dramatization of Superman’s dramatic teenage years from a network that specialized in teen drama… a Dawson’s Creek with superpowers, especially one that was intentionally avoiding the whole superhero angle of the show in favor of, well, teen angst and teen romance? Pass.

Of course, like I’m sure many of my fellow longtime comic geeks, I would tune in from time to time whenever I caught wind that they were introducing another DC character into the mix. A Bart Allen here, a Cyborg there, an Arthur Curry and the like. Minor dalliances which, more often than not (well, always actually) confirmed just how corny and under-budgeted the show was and how little we were actually missing.

For all its negative traits, the questionable acting, the choppy direction, the overplayed love triangles, the show actually started growing its audience in its final years as it finally caved and gave into its four-color roots. Oliver Queen/Green Arrow joined the cast (as a substitute for the unavailable Bruce Wayne/Batman role) as did Lois, and Supergirl, and there was the move out of Smallville to Metropolis, and Jimmy Olson and hints at a Justice League. By the time its final two seasons rolled around, Smallville was more a superhero show steeped in nighttime soap operatic. It was never actually good, but it was ambitious. It teased the comic geeks with enough tights and superpowers to keep us interested to the point that for seasons 9 and 10 I was a weekly viewer. One Geoff Johns-scribed episode brought in the JSA, another Booster Gold and Blue Beetle. There were ongoing storylines involving Amanda Waller, played by Pam Grier no less (that unfortunately fizzled badly), and Slade Wilson (another fizzle), and the sloppily-handled final season arc which squared Clark off against Darkseid (which was a mess). It was as painful to watch as it was fun, the show suffered from many things, the wooden acting of Tom Welling was chief among them, but at the same time Erica Durance nailed it as a tough, saucy, confident yet vulnerable Lois Lane (becoming my favorite live-action Lois ever). So for all the bad there was some cheeky goodness.

When it was over, it was well past its prime, taking ten years and 200+ episodes to make a man out of Superman was perhaps five years and a hundred episodes too many. In the final episode, though, they did finally get him there (a mid-30’s Welling wasn’t really as cut as he used to be and didn’t quite fill out the recycled Superman Returns costume to any impressive degree). Just as Superman’s career was beginning, dovetailing somewhat into a more faithful DCU (Byrne-era) interpretation of the character, the show ended. Had it continued on television, we would have had something a slight cut above the 90’s Lois and Clark series, but still not doing the character any justice with a modest budget and an ever disinterested lead. So it makes perfect sense to capitalize upon the “Season” structure of licensed ongoing-series, made popular by Buffy The Vampire Slayer, and turn Smallville into a comic book. There’s no budget, so anything can happen, the actors don’t age so flashbacks and flash forwards can be handled with ease, and the performances are in the hands of artists and in the minds of the reader.

What’s more, the series is in great hands. Brian Q. Miller – a writer for the show – is in charge, and so he knows the voices of the characters and understand the rhythm of the show in an experienced way. As well, he has the much beloved (pre-New 52) Batgirl series under his belt, which is a good sign that the man knows how to structure a comic book yarn and create endearing, lively characters upon the page.

In this extra-sized first issue (sad that we now consider a 30-page story “extra-sized”), there’s no mistaking the feel of being back in Smallville. Miller recaptures Chloe, Ollie, and Lois exactly as they were when we left them. He imbues Clark with more charm, personality and confidence than Welling ever played him with, and is given some leniency to rebuild Lex (following the events of the final season) and to highlight the immediate impact Superman has had on the world since his coming out. Millar wastes no time making use of the freedom of comic books without veering too drastically outside the Smallville wheelhouse by having Superman save a space station. It’s not super flashy, but its effective in easing the reader back into Smallville without shocking them by being too comic-booky from the onset (perhaps learning from the folly of Buffy Season 8).

The art from Pere Perez is effective, but tries too hard to capture the likenesses of the actors that it feels inorganic and inconsistent. There seems to be a lot of effort spent on those likenesses and it takes away from the rest of the panel, the pages and the book overall. From past exposure, I know Perez is a solid cartoonist and hopefully he can quickly establish his own take on the characters that allows him to render them quickly, consistently and effectively so that he can focus more on finer details and more refined pages.

Smallville fans will be pleased. I hesitate to call myself a Smallville fan, but I too am pleased. If you enjoyed the TV series, specifically in its later seasons, it’s a must read.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

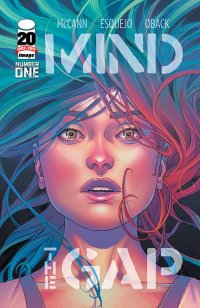

Mind The Gap #1 ($2.99, Image)

By D. S. Randlett

The first issue of Mind the Gap has a lot going for it. The art by Rodin Esquejo and Sonia Oback is great, and it features a decent enough story by Jim McCann with characters that have a certain whiff of reality that most first issues seem to lack. Here, we’re introduced to Elle Peterssen, who experiences the story disconnected from her body in a coma dreamworld. She’s been attacked on a subway platform, and it seems that her circumstances are part of a much larger and quite sinister game. We also meet her friends and her family, who experience the story in the waking world.

It’s an interesting concept, and it has the makings of a compelling paranormal mystery. But that’s precisely what makes this first issue hard to recommend on anything besides the merits of its technical competence. We meet a lot of characters here, but are given very few reasons to care about them beyond their relationship to the protagonist. I don’t know about you, but I need more to latch onto than “boyfriend” to establish a sense of connection with the story. As we’re in a mystery here, there are some aces that are intentionally being kept up the magician’s sleeve. This would be fine, but I felt like I was waiting for a reveal instead of being seduced into the story.

Mind the Gap isn’t at all bad, it just has a case of severe first-issue-itis. It certainly has a lot of merits that make it worth recommending. Like I said, the art is quite well done, and the characters are well written (even if a bit opaque at this point). There’s just a pallor of “not yet” hanging over the whole thing.

I have a feeling that when issue #4 is out, this will be a book that I eagerly await every month. But not yet.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

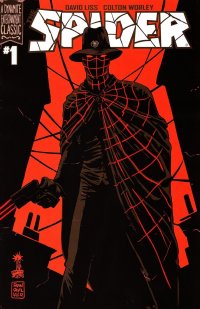

The Spider #1 (Dynamite, $3.99)

The Spider #1 (Dynamite, $3.99)

By Jeb D.

Contemporary readers could be forgiven for assuming that Dynamite’s grabbing of the license for The Spider was simply a way of preventing some other publisher from taking some of the bloom of their recently-launched Garth Ennis series of The Shadow: if there’s gonna be two gun-toting avengers in black cloak and slouch hat on the shelves, Dynamite might as well scoop up all the resultant bucks. It’s to the credit of writer David Liss and artist Colton Worley that it comes off slightly better than that.

The Spider, as you might imagine, was created (in 1933) as an instant knockoff of The Shadow; author Harry Steeger lacked Shadow creator Walter Gibson’s knack for the poetic, frenetic stream-of-consciousness, and The Spider’s stories resemble conventional hard-boiled detective novels more than Gibson’s Shadow pulps do (though he shares Gibson’s penchant for outré villains). And just as there are always music fans who want to tell you that, say, the Dave Clark Five or Merseybeats were somehow “purer” Brit-rock than The Beatles, or that the horseplay of the Ritz Brothers was superior to the genius of frère Marx, there’s a school of thought that says that The Spider’s less imaginative tough-guy routine (The Spider, rather like The Punisher, takes it for granted that we all already know what evil lurks in the hearts of men, and that the man who steps across that line has taken full responsibility for his actions, and will pay accordingly) is more of the “real deal” than The Shadow.

This is not the place to try and settle that debate (or just how many elements of The Spider later wound up on The Shadow’s radio series), but there’s no question that for a comic writer to take on The Spider in the wake of a just-launched Shadow series in the expert hands of Garth Ennis would seem creatively suicidal, and I give Liss props for stepping up. He takes one sidestep by updating the setting to a version of the present day, though with mixed results (these days, it’s evidently standard to toss a couple of blimps into your city skyline to signal that this isn’t exactly “our” world, but the significance of that isn’t immediately clear).

Millionaire and burned-out war vet Richard Wentworth carries on his crime-busting activities as The Spider with the secret help of his one-time fiance Nita Van Sloan (who originally preceded the pulp version of The Shadow’s Margo Lane), and an uncomfortable relationship with police detective Joe Hilt who (shades of Daredevil) is convinced that “freelance consultant” Wentworth is The Spider, but can’t prove it. This is pretty classic pulp stuff, and the mystery that Wentworth is helping to investigate is appropriately grisly.

The need to hit the classic marks as the story proceeds can make some of the “updating” feel awkward: tossing in references to cell phones, Russian gangsters, and anti-immigrant intolerance doesn’t do much to distract from the predictability of the story structure (am I the only one that never again wants to see an alley mugging carried out by thugs out of Central Casting?). On the other hand, Liss has taken the time to reimagine the characters themselves, so that their backstories and relationships are interesting and effective, though the info dump tends toward the plain and overtalky. The action may feel like warmed-over Shadow, but the background it’s playing against has been well thought out.

Worley performs a sort of straddling act, bringing noir shadings to the modern setting. For the most part, he succeeds (though his figure work can be inconsistent), and there is some imaginative layout work in the action scenes, but either he or Dynamite have made some odd choices regarding colors and registration, because faces and clothing sometimes seem to pop off the background like 2-dimensional cutouts; not a deal-breaker, but definitely distracting.

If you’re going to buy one new Dynamite comic series about a pulp-magazine avenger mowing down his enemies with a matched pair of automatics… well, it won’t be this one. But if the wait between installments of Ennis’ Shadow series feel too long, you could do worse than hook up with this latest incarnation of the Master of Men.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars