You can’t stop Ellen Page. She’s already a Toronto Fest vet, having appeared in films selected for the ’02, ’04 and ’05 festivals. In addition to this experimental teen runaway drama remix, Page appeared at Toronto this year in Juno (reviewed right here) and The Stone Angel. I hear she also spent a couple days working the Intercontinental concierge desk for college credit, and I’d swear that one of the mannequins in the Roots store was actually her as well.

You can’t stop Ellen Page. She’s already a Toronto Fest vet, having appeared in films selected for the ’02, ’04 and ’05 festivals. In addition to this experimental teen runaway drama remix, Page appeared at Toronto this year in Juno (reviewed right here) and The Stone Angel. I hear she also spent a couple days working the Intercontinental concierge desk for college credit, and I’d swear that one of the mannequins in the Roots store was actually her as well.

Bruce McDonald is also a festival vet, and one of the better-known semi-underground Canadian filmmakers. His work introduced me to Don McKellar in 1991 when I saw Highway 61 and he took up permanent residence in my ‘list of directors whose work I’ll always see’ when he was involved with McKellar’s television show Twitch City. He’s languished mostly in television ever since (Degrassi: The Next Generation, ftw) with intermittent feature output only thinly living up to his early potential.

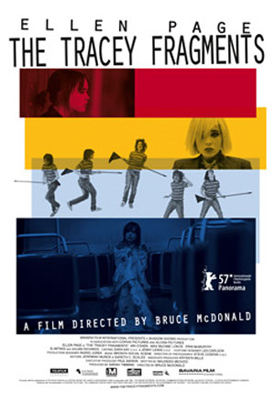

The Tracey Fragments, based on the novel by Maureen Medved, isn’t the film that’s going to bring him back to any sort of pseudo-prominence. Starring Page as the title character, the film is the most splintered of several self-consciously post-modern flicks that populated Toronto this year. (Diary of the Dead, Redacted, My Winnipeg) It’s part DeStijl, part public service announcement; black lines break the screen into blocks, but the content is grey and cold and too often plainly didactic.

This image from the film only begins to communicate how broken-up the visual storytelling is. Inset windows fade in and out constantly; single shots are allowed to take charge of the entire frame, but rarely. The design is not without purpose; Tracey’s mind is typically teenage (as I remember being, anyway) which means swirling with a mix of truth, fantasy and fiction.

We’re introduced to Tracey Berkowitz as she huddles in a seat at the back of a public bus, swaddled in a shower curtain. Fragments of story are tossed around, each disconnected but obviously pointing to some central trauma or upset. We see Tracey’s family, the little brother that barks like a dog, and Billy Zero, the stylish rocker boyfriend Tracey insists loves her.

Tracey’s life is as raw as the film’s storytelling. Fellow students call her ‘it’. Boys shun or harass. While her brother Sonny is cheerful and follows his sister like the puppy he pretends to be, her parents are at times expressionless and silent, then braying and overbearing in their attempt to manage her life.

They’re also the film’s weakest links. Ari Cohen as Mr. Berkowitz and an actress whose name I can’t dig up as the mother are too arch, too obviously putting on a show. I could never find any credibility in either performance, whether they were meant to be legit descriptions of the couple or exaggerated fever-dream impressions emanating from Tracey.

Mom and pop try to ground her, and insist upon counseling sessions with a female therapist who, entertainingly but too pointedly cast by McDonald, is actor Julian Richings in drag. Naturally Tracey runs away, though it takes the disappearance of her brother and destruction of her central fantasy to precipitate the act.

In disassociative but often effective image/verse, Tracey spins a tale of an outcast high schooler who’s rescued from mediocrity by the new kid in school. But that’s not quite how it is. There are implications of abuse and/or rape. The intrusion of skeevy Lance (from Toronto, he always says) casts a pall over Tracey’s tale of love with Billy Zero. Some of her story is too obviously intended to shock ("He put his cock in me and told me he loved me," explains the teen) while family dinner settings could be recast as television ads warning parents of the dangers of ignoring their children.

Through it all is Page, earnestly putting herself forward as this broken, lost little girl. It’s almost a one-woman show. Oddly, while her performance isn’t variable at all — she’s remarkably solid and consistent — it feels as fractured as the movie it’s in. That’s in part because her particular brand of eager hysterics and chin-jutting emphasis is overused. There’s entirely too much opportunity for Page to show how psychically battered Tracey is, and very few chances for her to be a kid.

Obviously McDonald is to blame there more than anyone, and I can’t help but imagine The Tracey Fragments as a stronger, more balanced piece if the same techniques used to splatter the girl’s horrors onto the screen were used to bring out those passing, fanciful moments of teenage bliss, as well. We see brief fantasies of love and fame, but these play like psychotic retreats, not innocent daydreams.

(From what I can tell, the original novel is almost like Hubert Selby applied to a teenage girl, in which case the adaptation is certainly accurate. I can’t say that makes it more effective, however.)

There’s a lot I admire about this movie. It’s adventurous and unafraid and when McDonald’s technique and Page’s come together, the result is deeply unnerving and melancholy. When the mixture doesn’t gel, the mix is just morose. McDonald’s best work is imbued with a rock and roll spirit — Iggy Pop and Chuck Berry translated into a circle of off-center characters. But even Iggy’s darkest, most enraged lyrics have a flash of humor and life that’s missing from too much of this story.