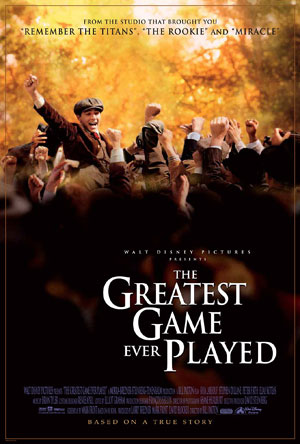

Golf is a boring game. Bill Paxton knows this, and so he spices his golf film, The Greatest Game Ever Played, up with plenty of CGI madness. You know you’re in for something a little outside a standard golf film when, in the opening scene, the camera pans across the thatched roof of a shanty and you hear a “Whoooooooosh!” noise. From there we enter a world where we get golf club POVs, a close up examination of the relationship between a ladybug and a golf ball in flight and the most crashing booms and loud thwacks since Bad Boys II.

Golf is a boring game. Bill Paxton knows this, and so he spices his golf film, The Greatest Game Ever Played, up with plenty of CGI madness. You know you’re in for something a little outside a standard golf film when, in the opening scene, the camera pans across the thatched roof of a shanty and you hear a “Whoooooooosh!” noise. From there we enter a world where we get golf club POVs, a close up examination of the relationship between a ladybug and a golf ball in flight and the most crashing booms and loud thwacks since Bad Boys II.

It’s almost enough to make golf interesting. In the end the CGI sort of just focuses your attention on how boring the game really is, though, because you become so hyper-aware of the attempts to make the game seem X-TREME! Where golf gets interesting, and what makes the movie work, is where it becomes a game about a man against himself. It’s the mountain climbing of small ball games.

Shia LaBeouf (whose name I believe means “Afraid of the Beef”) is Francis Ouimet, a golf caddy at an exclusive Boston golf course and club. He lives across the street with his two embarrassing stereotypical parents – Elias Koteas plays the dad with a French accent not even Pepe Le Pew could stomach. Francis loves the game of golf and starts playing on his school team, getting some renown. Enough renown that two sketchy (and I mean that as “hastily drawn,” not as in “perverts.” That would have been a very interesting film indeed) characters – members of the club – see potential in young Francis, and they break through class barriers to get him in to the Caddy 5000.

Dad hates the idea. It’s not a profession, you can’t feed your family on golf wages. After losing the Caddy Ultimate, Francis kowtows to his dad’s wishes and quits playing. But soon the US Open – which is “Open” to all players – comes to the club, and Francis finds himself back in the game, with a ten year old wise ass caddy at his side, and playing against Harry Vardon, his one-time golf hero.

Vardon is the opponent, but he’s not the nemesis. In fact, Vardon comes from a background very similar to Francis, and while he’s the most successful golfer on Earth, he still hasn’t found the respect from the upper class that he craves. It’s that class barrier that Paxton and screenwriter Mark Frost want to examine, and it’s almost an interesting thing to look at.

Almost because golf is the most inherently elitist sport there is. You can’t just go out on the street with your friends and play some rounds of golf. You need a big course, which is expensive. You need a number of clubs, which are expensive. Why is basketball the most popular sport for poor kids? Because it’s the easiest to play in an urban setting. Even baseball has been translated into an urban street sport with stickball. But golf is forever the game of the suburbs. And that’s not even taking into account the basic shittiness of a game that gobbles up that much land, which could either be used to house people or to create a public green area.

After a while the whole conceit of Francis opening this sport up to the common man just becomes tiresome, as any look at the popular culture will tell that it’s just not true. Hell, look how long it took to just get a black guy in the game. Ouimet may have played a great game of golf, but the ramifications were minor.

Of course if the class war stuff doesn’t work for you, there’s always the reliable tearjerker of the boy who wants his dad’s approval. You can probably see where that one’s going in this film. That’s one of the biggest problems with The Greatest Game Ever Played – it’s like a series of clichés strung together. After watching Walk the Line, the Johnny Cash biopic, it dawned on me that any musician biopic will likely end up being a samey rehash of that genre – sports films are really the same way. There are very few variables in a sports movie, and the real tension in them is figuring out will the hero win or will he lose and learn a valuable lesson about trying your best? You can usually tell the answer within fifteen minutes of the opening.

Where Greatest Game breaks the mold, though, is in showing us the game as Francis against himself. His own worst enemy is his nerves. I guess in some ways this is the equivalent of a cripple guy sports movie, even though Francis is in no way crippled. But those stories have the protagonist not mainly competing with others but against his bad legs or whatever. Still, I found the film most fascinating in the stretches where Francis has to just overcome his own problems.

Paxton tries a little too hard with some of the slam bang golf stuff, but he has made a very beautiful movie. It’s lush, and cinematographer Shane Hurlbut has found a way to make the film look both old fashioned and modern. Paxton’s a gifted filmmaker for sure, but he’s not doing much original here.

Shia LaBeouf has a turn of the century look about him, and he’s surprisingly OK in the role. I have always found him mildly irritating, but here he tamps down his Disney Channel instincts and plays Francis with a lot of quiet dignity. Greatest Game feels like his first step into a larger, more adult world.

Greatest Game is the kind of movie that is calculated to get a tear out of you. It’s not a bad film, but it’s not a terribly good one either. It manages to be surprisingly entertaining for a golf movie, but otherwise it has nothing new going on.