There’s a lot that’s great about Everything is Illuminated, but one of the things that struck me is that this is the auspicious directorial debut for an actor. Liev Schreiber didn’t just direct this adaptation of Jonathan Safran Foer’s critically acclaimed novel, he wrote the screenplay, yet this movie isn’t filled with actorly moments. In a story about a Jewish American’s trip to Ukraine to find the woman who saved his grandfather from the Nazis you might expect to find many moments where emotions could be milked, giving the leads big scenes to play. But Schreiber doesn’t do that, and instead has made a film that is restrained and ultimately poetic in its simplicity.

There’s a lot that’s great about Everything is Illuminated, but one of the things that struck me is that this is the auspicious directorial debut for an actor. Liev Schreiber didn’t just direct this adaptation of Jonathan Safran Foer’s critically acclaimed novel, he wrote the screenplay, yet this movie isn’t filled with actorly moments. In a story about a Jewish American’s trip to Ukraine to find the woman who saved his grandfather from the Nazis you might expect to find many moments where emotions could be milked, giving the leads big scenes to play. But Schreiber doesn’t do that, and instead has made a film that is restrained and ultimately poetic in its simplicity.

The American returning to the homeland happens to be named Jonathan Safran Foer, a young writer who obsessively collects items relating to his family. In Ukraine he is guided by a bizarre trio – Alex, a young man who loves American culture and Negroes, Alex’s grandfather, a gruff old man who believes he is blind (he is, of course, the driver), and Sammy Davis Junior Junior, the “officious seeing eye bitch” for Alex’s grandfather, a dog that is deranged but “so, so playful.” The three journey to Trachimbrod, a town that does not appear on any map, to find a woman who Foer only knows of through a yellowed photograph with an inscription that he is assumes is by his grandfather.

Schreiber finds the perfect tone for this film, a tone that I find very Jewish. It’s wistful and sad, yet very funny. There are heartbreaking moments that moved me to tears and there are hilarious moments that had me laughing over lines of dialogue, but mostly the film kept me quietly enraptured, often with a grin on my face. The trip isn’t filled with incident – most of the time is spent in a tiny Eastern European car – but Schreiber keeps it from being dull with that tone, and with the interaction between these strange characters and a light sprinkling of delightful detail. He achieves an almost magical-realist feel in the film, without ever actually going into fantasy.

At the heart of the story is this search – a very rigid search, as Alex says – that ends in answers and personal discoveries. But around that swirls so many things that I can’t even begin to write about them without making this review intolerably long. Jonathan is one of the few young Americans Alex has known, and the understanding of American culture Alex has, informed by hip hop and Michael Jackson, has no place for this strange outsider, this bug-eyed vegetarian in a country where sausage is on every plate. Grandfather is of the WWII generation, and he must come to grips with his own secrets from the time of the Holocaust, and Alex must come to understand his people’s role in the persecution of the Jews. Jonathan, meanwhile, searches for connections to his heritage and finds it in a fairly unlikely place.

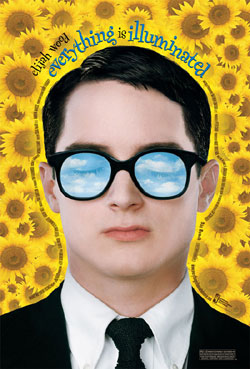

Elijah Wood has spent the years after The Lord of the Rings taking on roles that might distance him from Frodo. I suspect it isn’t from a dislike of those films, but rather from being aware that he’s a hairbreadth from being typecast forever. Here he finds the role that should make people see him as an actor, and not just Frodo in a different setting. Wood has huge, expressive eyes which made him a favorite of teen girls for years and which he used to truly create the soul of Frodo. Here these eyes are magnified to absurd proportions behind massive spectacles, and they’re used to the opposite effect. Jonathan is an observer, shielded behind the glasses, always separate from what he’s looking at.

Elijah Wood has spent the years after The Lord of the Rings taking on roles that might distance him from Frodo. I suspect it isn’t from a dislike of those films, but rather from being aware that he’s a hairbreadth from being typecast forever. Here he finds the role that should make people see him as an actor, and not just Frodo in a different setting. Wood has huge, expressive eyes which made him a favorite of teen girls for years and which he used to truly create the soul of Frodo. Here these eyes are magnified to absurd proportions behind massive spectacles, and they’re used to the opposite effect. Jonathan is an observer, shielded behind the glasses, always separate from what he’s looking at.

It’s a tough role. Jonathan is inscrutable at best. He’s the proverbial stranger in a strange land, surrounded by people who don’t understand him (although it seems pretty obvious that people not understanding him is a regular part of his life), either as a person or even on a simple language level. Jonathan is the character who initiates this journey, but he may not be the one with the most to learn at the end. Wood is a good enough actor to bring us through Jonathan’s distance and strangeness and make us care about him, and to want to understand him better.

Wood’s job isn’t made any easier by Eugene Hutz. The lead singer of the band Gogol Bordello, a real Ukrainian, makes his acting debut here, and he steals every scene he’s in, which is the vast majority of them. Alex is given to malapropisms, completely mangling the English language, and in lesser hands this would get tiresome (and it does, in the book. I loved the film so much I picked up the novel and found that by page three I had had quite enough of Alex’s narration), but Hutz imbues Alex with so much depth and humanity that you’re feeling bad about laughing at him while you can’t help but laugh at him. Alex is the opposite of Jonathan, a motor mouth who claims to be good with the ladies and a fine dancer, but he’s really the same as Jonathan.

Boris Leskin is Grandfather. Leskin has been working in Eastern European and Soviet film since the 50s, and his craggy face shows every day of his life. He’s a joy here, a nasty old man who is spending the final years of his life wallowing in self pity. He’s completely acerbic, and also quietly sad. It’s his series of understandings, his illuminations, that were the most moving for me. And which culminated in a scene that I am dying to write about here, but can’t. It’s been a long time since I have so much wanted to discuss the meanings of a scene in a film.

Fans of the novel may be disappointed to learn that Schreiber has cut a whole storyline, a fantasy bit about the life of a shtetl in Ukraine a few hundred years ago. When I saw the film I hadn’t read the book, and the shtetl scenes weren’t missed. After having read the book I can say that they still aren’t. Schreiber has found the heart of the material and animated it like a benevolent golem. He has also crafted a movie that looks great. While Ukraine may be a bleak and grey country, cinematographer Matthew Libatique finds the shabby beauty in so many places. And there’s one moment, where the characters come upon a house set deep in a field of sunflowers, that is breathtaking. In front of the house is a number of white sheets hanging on clotheslines, and as the wind blows them back and forth I momentarily thought they were dancers.

After the end of WWII my grandfather’s army unit visited one of the closed concentration  camp, helping in the clean-up effort. He died last year, one of the many people of his generation, the generation who were first hand witnesses to the Shoah, who are gone. Very soon there will be no one alive who was there when these things were happening. Everything is Illuminated is a Holocaust movie as coda to that generation, a film about the way things pass between generations. It’s a movie that at first seems to be only a little bit about the Holocaust, but by the end makes you understand how everything that has come before really is about it.

camp, helping in the clean-up effort. He died last year, one of the many people of his generation, the generation who were first hand witnesses to the Shoah, who are gone. Very soon there will be no one alive who was there when these things were happening. Everything is Illuminated is a Holocaust movie as coda to that generation, a film about the way things pass between generations. It’s a movie that at first seems to be only a little bit about the Holocaust, but by the end makes you understand how everything that has come before really is about it.

I’ve heard people describe the film as precious. I don’t know if I could disagree with that – it’s too self-conscious and too aware of its own narrative not to be. Other people have described it as a low rent Wes Anderson film, which is a stunningly incorrect reading of the movie. Quite simply, Everything is Illuminated is a wonderful film, a moving film, and a funny film. It’s not a movie that will make a huge splash this year, I suspect, but is a movie that people will look back on in twenty years and wonder if we knew how lucky we were to be around when someone was making movies like this.

9.3 out of 10