Sometimes a horse comes out of the gate strong and dominates the track for the first few laps but then, suddenly and tragically, a leg goes – just buckles and snaps – and the horse is down, the rider is thrown, and their race is over. This same thing happens to Anthony Minghella’s Breaking and Entering, a movie that begins so strongly as to make the awfulness of the final act and a half stand out in stark relief. Breaking and Entering is a movie that actually deflates as it goes along, leaving the cast standing in the ruins gamely trying to go on.

Sometimes a horse comes out of the gate strong and dominates the track for the first few laps but then, suddenly and tragically, a leg goes – just buckles and snaps – and the horse is down, the rider is thrown, and their race is over. This same thing happens to Anthony Minghella’s Breaking and Entering, a movie that begins so strongly as to make the awfulness of the final act and a half stand out in stark relief. Breaking and Entering is a movie that actually deflates as it goes along, leaving the cast standing in the ruins gamely trying to go on.

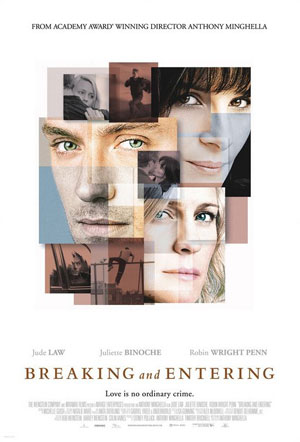

Jude Law is an architect who has just moved his offices to a tougher neighborhood in London; he and partner Martin Freeman are environmentally minded, and they are building a massive development that will reshape this neighborhood. Things are going well at work, but at home things are tougher: Law’s been living with Robin Wright Penn, playing a half-Swede/half-American and her daughter, a mildly autistic gymnast. The girl won’t sleep, is endlessly difficult and Penn finds herself trapped in a life she never exactly bargained for.

Meanwhile a Serbian criminal gang haunts the firm’s new neighborhood. A couple of parkour kids work for them, improbably racing across the cityscape and getting into buildings into unusual ways. The new architecture firm – all glass and steel and plasma TVs and Macs – proves to be an irresistible target, and they break in and clean the place out. And then they do it again.

At this point Minghella has me. The do-gooder gentrifier versus the immigrant criminals who maybe aren’t that nasty (the parkour kids, anyway) is the sort of modern moral grey zone that movies like Crash insist on oversimplifying. He makes things more interesting by having Freeman interested in one of the cleaning staff – an immigrant herself who comes under suspicion by the police because the robbers used an access code to turn off the building alarm. The characters are intriguingly sketched, as is the environment. There’s an atmosphere of gentle dread that’s intriguing, and things continue to get better as Freeman and Law stake out their office at night and meet a mouthy Eastern European hooker played by Vera Farmiga in a terrific performance.

But then Minghella throws it all away – Law sees the parkour boys breaking in and chases one of them all the way home… and falls in love with his mother. Juliette Binoche is the mother, and while it’s fairly easy to imagine why Law would want to get it on with her – she’s gorgeous, even without make-up – it’s impossible to see how he falls in love. His problem with Penn is that she has been so depressed, but Binoche makes her seem positively high-spirited in comparison. Binoche and the son escaped Serbia during the civil war, but she left her husband behind, and he was murdered. She hates England and hates what her son is becoming. In a lot of ways she’s the exact same as Penn, except that we hear about how joyful Penn was at the beginning of the relationship; outside of one scene at a playground we never get that from Binoche.

And just like that the movie crashes to a halt as this affair takes over. All of the interesting background characters fade away and we’re dealing almost only with this unbelievable union. The movie then turns into a minor thriller, but it never has the wherewithal to go down that path; finally it turns into a sermon on reconciliation, and it feels just as phony as a homily from a defrocked priest.

The affair is so clumsily grafted onto the scenario that it feels as though Minghella was just clearing out his unused ideas drawer, and some of the writing makes it seem like he was using first drafts. At one point near the end Jude Law actually says – out loud! – that perhaps his fondness for metaphors is itself a metaphor. Unless you’re about to break the fourth wall, that kind of dialogue is inexcusable, but it’s all over the place in the last act as Minghella must have his characters reach emotional conclusions quickly and without too much messy screen time. In the final reels the long-forgotten secondary characters dutifully return, but all the shine is off them. Martin Freeman’s character, who is, as every Freeman character is, so enjoyable, has had an entire storyline happen offscreen, and you can’t help but suspect that it’s more organic than what happened with Law and Binoche. Ray Winstone is a cop who barely had time to register before being shuffled off for the majority of the film, and he returns at the end to tie everything up like the hand of narrative closure reaching down from the heavens.

Anthony Minghella is, without doubt, a great filmmaker, and the idea of him finally coming back to an original script so many years after Truly, Madly, Deeply, was an exciting prospect. Which is what makes Breaking and Entering doubly crushing – if it had begun poorly I would have been able to adapt to its badness more quickly, but as it is, watching the movie is like having a lovely drive and suddenly driving into an endless chasm.