As a director, Sean Penn has always chased the ineffable. But the films (The Indian Runner, The Crossing Guard and The Pledge), while fascinating for their moody, unconventional texture, have always fallen a tad short of satisfying. Though you were grateful for the experience of watching them, there was always something closed off about their anguish, as if Penn couldn’t trust the viewer enough to let them get on his wavelength. They were the films of an artist who wanted us to feel his pain, but wasn’t sure if he was comfortable with us understanding it.

As a director, Sean Penn has always chased the ineffable. But the films (The Indian Runner, The Crossing Guard and The Pledge), while fascinating for their moody, unconventional texture, have always fallen a tad short of satisfying. Though you were grateful for the experience of watching them, there was always something closed off about their anguish, as if Penn couldn’t trust the viewer enough to let them get on his wavelength. They were the films of an artist who wanted us to feel his pain, but wasn’t sure if he was comfortable with us understanding it.

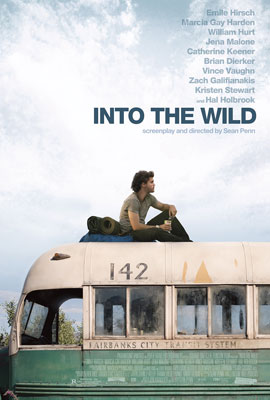

This won’t be a problem with Into the Wild, a big-hearted adaptation of Jon Krakauer’s best-selling tome about the impulsive rite of passage that ultimately claimed the life of young Chris McCandless, who, after nearly two years on the road, ventured north to Alaska and never ventured out – at least, not physically. This is where Krakauer ends, and Penn begins. Perhaps only someone as fearlessly compassionate as Penn – and whatever you think of the man’s political convictions, you cannot doubt that he cares deeply for his fellow man – could solve the enigma of McCandless. Rather than criticize the young man for his recklessness, Penn tethers it to the wanderlust that exists in all of us, and, through McCandless, we experience the purest form of that journey when its pull is at its strongest. This isn’t a post-college jaunt through Europe or a summer spent following a jam band; this is a trip to the core of oneself, an attempt to learn who we are and earn that identity.

There will be those who resist the sacrificial beauty of McCandless’s death (I even hesitate describing it as such, but that’s how it hit me), but listening to my friends and reading the reactions from folks online, I’m confident that there will be just as many who connect to it, who see something galvanic in it. And the copycat twentysomethings who head for Slab City, who trample the Alaskan wilderness seeking the same experience will get it all wrong; Into the Wild is about finding your own path and listening to your own muse. That might sound sickeningly idealistic, but Penn’s film knocks one back to a sort of unspoiled, youthful state; cynicism has no place in his universe.

After years of struggling to find his voice as a filmmaker, it’s nice to hear Penn talk openly and confidently about his process, as he did at a press conference held last week at the Beverly Hills Four Seasons. Though there was a flash of the old anger when one journalist questioned the wisdom of McCandless’s fatal foray into the Alaskan wilderness, Penn’s ire had more to do with the attitude being expressed, i.e. that McCandless was somehow endangering the lives of others by daring to figure out and survive the harshness of that environment without the requisite knowledge or preparedness. Other than that, he was in terrific spirits – though some of that joy was undoubtedly due to the unexpected presence of Pearl Jam frontman Eddie Vedder, whose soundtrack is an indispensable element of the film.

Q: You’ve made three films about men trying to escape their past. What continues to draw you that theme?

Penn: I could probably give you a very long-winded answer that had some truth to it, but I would say that the basic nature of it is not very analytical in terms of what brings me to [that theme]. Its probably first and foremost about being a man who is trying to come to terms with his past.

Q: Sean, can you discuss the significance of the Sharon Olds poem that you incorporated into the narration?

Penn: Yeah, I’d read that poem some years before. It really stuck with me, and it got me into reading her stuff. It really made an impression on me. She’s a great writer.

I’m in a lucky club. I had a very supportive, loving family. But 92.6% of my friends throughout growing up and today didn’t have that. It seemed so acute. So when I started to write, [Olds’s] poem had been in my head for about five years. But the book had been there for ten years. And when I started writing [the screenplay], I got to page three, and that poem just jacked me. It was a way in to something early in the picture. And then I very quickly wanted to make sure I could use it if I was going to go on down that road. So I called my partner, Art Linson. We had bought the rights to the book together. I said, "We can spend a little more money. Let’s get in touch with this poet, Sharon Olds, and see if we can get the rights to [her poem]. And, as long as she is a women and a great writer, I might just like to see if we can hook in and get her consultation on the narration when we’re in post-production." I’d written the narration already, but I knew I was going to want a woman’s touch. And *that* woman’s if I could get it. So we made an overall deal with Sharon, I finished the script, and then came back to it in the end. I had recorded all of my original narration with Jena [Malone] prior to shooting. Then I got Jena and Carine McCandless and Sharon Olds and myself in a recording studio in San Francisco, and we did our kind of final spin-around off of what I had written in the first place. And we just got it to be better, kind of more from a woman’s voice.

Q: Chris didn’t seem to have a very well thought out exit strategy once he got to Alaska. I was wondering if you see any parallels to what’s happened to America’s foreign policy?

Penn: No, I don’t see a parallel in that way because Chris wasn’t putting any babies at risk. I think that intention counts for a lot, and I don’t think ours can compete in the level of purity. But, also, I don’t know that I entirely agree; there is no exit strategy from Mother Nature if she doesn’t want you to have one. You can go to any length you want. The degree to which he wanted to challenge himself is the degree to which he made a stripped-down trip, and I think that the exit that was necessary was an exit from inauthenticity. Then you’re going to see if you can handle the rest – if you get the luck and good fortune to do so.

Q: Sean and Eddie, can you talk a bit about your collaborative process?

Penn: I’ll start and hand it off to [Eddie]. We go back quite a ways; I guess back to Dead Man Walking. It may be a little before that in a backstage kind of way. I’m forty-seven, so there’s not too much music that comes after ’68 that doesn’t feel like it’s been done before. And then comes his voice. His voice sat me down – as a songwriter as well as just a singer. There was that and, of course, I was predisposed to want him to like me when we met. And it didn’t work out too well the first time. (Laughs) But then as it went along, I just felt a kind of creative connection. Or at least aspired to it. I even asked him to play the lead in a movie that I’d written at one point. Maybe he’ll you about that. But on [Into the Wild], I’d written the script to be, in part, told by song, so I’d left out narrative in those transitional sequences knowing just the seed of what I needed from the songs to close those gaps. It was about halfway through shooting, really, and through Emile’s performance, that I started feeling that this is Eddie’s voice. This was the musical soul, the voice of what Emile was bringing. So I asked, and I’ll let him take it from here.

Eddie Vedder: First of all, don’t feel like you need to ask me questions; I’m just happy to be sitting this close to whom I consider not just a great human, but a master at what he does, in all the things he does. (Indicating the front row of journalists:) Those are pretty good seats, but this one’s even better. I couldn’t turn down that opportunity.

Um, where did we leave off?

Penn: We left off at when I called you.

Vedder: Yeah. I think if you go back to the poet… Sean had some resources. And people call him back immediately because of the amount of respect he’s earned over the years. I was just another one of those calls and immediately I responded, and said goodbye to what I thought was going to be a vacation after doing a long stretch with the band. Our friendship is incredibly important to me. We’ve had some really memorable times, whether it’s running rapids or having coffee – and it’s amazing how those things with Sean can be really similar. (Laughter) But to work with Sean… that’s where you get into the good stuff, you know, beyond "Hey, how’re you doin’ and how’s the family?" The work is really where it gets exciting. And it was a real gift. I’m really glad that he heard my voice in all of that.

Q: Have either of you ever felt a call to the wild? A call to get away from the bustle of the city?

Penn: I think I can say "Yes", and I think [Eddie] would tell you the same to varying degrees, in different ways. That’s one of the things that made me so interested about this story. I’ve been wrong about these perceptions before, but the way I made this movie movie is that it’s true of everybody in this room and everybody outside this room, too. This is a very universal thing, this wanderlust.

Vedder: For me, if I’m not on tour or if I’m not in the studio or something, I’m out in nature somewhere, usually near some kind of ocean. Playing music has afforded me that; it’s not lost on me that it’s a tremendous opportunity to be able to spend your life surrounded by nature. I will say, though, that I have a three-year-old daughter now. I’m glad I did things in my twenties that were more reckless, because at some point you realize you have a responsibility beyond yourself and your need for adrenaline. I’m still looking for bigger waves, and I feel I can jump up a few more feet before I go back to the longboard. But I’m glad I did that stuff at the time. And for people who see this movie… if they haven’t done that in their life, I think it’s going to hit them pretty hard.

Q: Sean, why did you want to dramatize Chris McCandless’s story?

Penn: I read the book when it came out. I read it twice in a row. And I started trying to get the rights to it the next day. The impression that Jon Krakauer’s book made on me and that Chris McCandless’s story made on me was the movie that I made. That’s what I read – and then was embellished by my collaborators later. But the structure, the skeleton of this thing… Jon had me seventy-five percent towards the movie that you saw already, and then I had twenty-five percent of making cinematic what he had made in literature. I could answer this question in boring length, but I think the movie should answer it for me. This is what I intended to make. This is the movie. It would be very fair for somebody to criticize something they didn’t like in the movie, or that they felt more intelligent than, or more heartfelt than. But it would be factually wrong for them to say that I hadn’t succeeded in telling the story as I intended. So I would say that I feel very complete in that it answers [your question] for me.

Q: What particularly struck me was Chris’s destruction of his former self. Can you talk about that, and also how you decided to cast Hal Holbrook as Ron Franz?

Penn: I’ll start from the beginning and work back. Hal Holbrook was someone I’d done one of my first television movies with when I was eighteen or nineteen. He’d made such a strong impression on me, and a lasting one in terms of what being an actor was. Despite that there’s no such thing as a better actor than Hal, there’s something inherently moving about the integrity in the man. I had wanted to work with Hal on all kinds of things, and I snuck his name into the ears of directors along the years that I was working with. I tried to think of things to maybe direct him in. So when this fit, it just fit. I called him up, and the extent of my direction was pretty much "action" and "cut". Hal Holbrook made that performance, and he’s great.

As for the first part of your question, there’s a thing Eddie said last night about "healthy rebellion." The way that Walt McCandless described his son to me was that Chris didn’t want to burn down the building, he just dismissed it. I don’t think he wanted to burn down Chris McCandless in terms of where he’d started and the fraudulence he thought he was carrying on his back; I think he just wanted to dismiss it. In most ways, Chris was a young man who, way ahead of his time, knew who he was and just had to find a place that would accept him. Once he did that, he would have the muscles to offer something back to a community, to a family, to a woman, to whomever. And it was always on that basis that I approached him.

Q: Sean, I loved your "Metaphor-Off" with Steven Colbert. I was wondering if you had any new metaphors that you might use to describe this film.

Penn: Again, I’m having separation anxiety on this movie. I’ve never had that before. I always like to have at least ten people who relate to my movies, and I always had to be the tenth on the [last three movies], so I could never let them go. This one is more of what I like to say is "everybody’s movie". It was when I started it, and it was before I started it. Chris’s gift is too generous for me to claim it. I just would like for it to answer for itself every time it can.

Q: Eddie, the music industry has changed so much. I remember the days when Ticketmaster was the big problem. What is your sense of the music industry now?

Vedder: I think as of two weeks ago, Ticketmaster is now gone. (Laughter) So there’s something about longevity; it’s nice to outlast something as big and giant and powerful as that.

But the answer to this is a three or four hour discussion at the end of which there’s just as many new questions as there are answers. It’s a bit strange for me that people are weighing in on the new record, and yet it’s not for sale. They’ve all downloaded it. As an artist, the problem of not selling records, if that’s what we’re talking about, is that you always used to figure that people weren’t buying your records because they didn’t like them. I agree with that, too. And that could be the case. But a lot of people are getting their music without having to pay for it. It’s only $12.00. I ordered eggs at a little restaurant in Seattle yesterday, and that was $9.50. I’m thinking, "You can’t spend an extra two bucks for a record that I put my heart and soul into?" I think the problem is that yoiu’re going to have to charge more for tickets, which is something we’ve always been reluctant to do. It’s either that, or you’re going to have to start accepting sponsorships, or start selling your music to Viagra commercials and supporting things like artificial erections. (Laughter) As an artist, that puts you in an interesting position, and I don’t know what we’re going to do. But I’m glad we gave money away when we did, when it came in from making records. But it’s a little different now.

Q: Sean, I want to get a sense of your process in deciding how objective you could be. The movie won me over, and I really cared for Chris. But then I looked into his story, and I found an essay by a park ranger who said what he did wasn’t exactly daring, but stupid. And I found the more I looked into it, the more I agreed with that. There was a hand-operated tram a mile away from the point where he tried to cross the river, and any decent map that any hiker might carry around with them would’ve shown this. It seems like he picked and chose what he wanted to leave behind of society. He went out there without an axe, but he did take a rifle with a telescopic sight. I’d like to get your sense of how objective you could be, and did you make a conscious effort to not romanticize Chris?

Penn: I don’t know how objective a person who wears a brown shirt and a patch on their shoulder and follows instructions all day [can be], so I’m not all that interested in what the park rangers have to say. I accept that there is an automatic instinct to judge those you envy and who have more courage than you do, and I think that, while he rides around on his four-wheeler on a CB radio getting fat, Chris McCandless has gone 113 days fucking alone in the most unforgiving wilderness that god ever created. You just go out there and take a look at it sometime. This is a guy that wanted to challenge himself in a way that for us to judge would be just ridiculous. When I buy a Nikon camera, I have no tolerance for the instructions; I’m ready to make some mistakes using it and get some bad pictures back until I’ve figured it out for myself. And I guarantee that if you do it that way, by the time you learn it, you learn it better than any instructions will tell you. If that’s what he wanted to do… he could have also put the rifle away and come out with a bow and arrow. He could have gone out there naked in the woods. You go out there and you challenge yourself the way that you want to challenge yourself. But I think that this isn’t about whether there was more equipment to be bought at Patagonia; it’s about somebody who had a will that is so uncommon today, a lack of addiction to comfort that is so uncommon and is so necessary to become common, or humankind doesn’t survive the next century. I’m just not willing to participate in it. I welcome anybody’s criticism, and they can discuss it in that way or any way that they want to about Chris McCandless as I always have myself. But I would caution you on listening to people in uniforms on this issue.

Q: But [the park ranger] is the guy who has to go in and rescue kids like Chris. You say he’s getting fat riding around on his four-wheeler, but he’s the guy who has to go out there to rescue people like the Coast Guard does sailors.

Penn: But you just told me the guy said he wasn’t in any hazardous condition. What’s the big deal of driving his four-wheeler out and rescuing him then? He didn’t bring anybody into hazard with what he was doing. We don’t live our lives to avoid bureaucratic mandates of what your job description is to go in and do something or *don’t* do something. Put it on yourself. You’re going to sit there and tell me… you’ve got children?

Q: Yes, I do.

Penn: You never corrupted them or fucked them up in any way with any of your shit? There’s no such thing as that, right? Alright. So who’s a bigger fuck-up: Chris McCandless for hurting himself or you for hurting your kids? I mean, we’ve all got our shit – and me too, by the way. I’m not attacking you. I’m just saying that the point of this thing is the heroism of this will and this courage that this young man had. And all the rest of it is somebody else’s folly for me.

Q: Eddie, you mentioned your daughter Olivia earlier. What kind of advice would you give her if, in twenty years, she tells you she wants to go on a journey like Chris McCandless did?

Vedder: Well, the initial reaction is to send a security guard along to stay fifty yards away and keep an eye on her at all times. I know that no matter what I do… and already she’s been provided a life of traveling. I didn’t get to New York City until I was twenty-five or Europe until I was twenty-six; she’s been to all of these places six or seven times. She’s already beyond me in terms of her comfortability around other people. So with all that, even though I think she’s going to have a great upbringing, and I’m trying to break any chain of negative parenting that I might’ve survived… I know that she’s going to go through a time when she has to assert her independence. And I’m going to have to just encourage that.

Q: Sean, has the McCandless family shared their feelings on the film?

Penn: Yes. I can’t go to the point of disclosing private conversations with them. I mean, this was an incredibly selfless and brave thing in my view for them to allow his story to be shared, but at the end of the day I’m always aware that if you take away all of the flaws of the family, you’ve still got two parents who are watching the story of their lost child they loved dying. So this is not a pleasant experience for them. But I hope that it will be a healing one, and I know that they’re very supportive of it. It’s one of the trickiest things involved in making a movie like this; it’s the double-edged sword of making speculations about someone you didn’t know… and about being trusted in the hands of his parents on such a triumphant but difficult story. These are people I consider friends of mine, and I have a great respect for [these] very intelligent, very caring people. I did have their help throughout, and I would call it a partnership [especially] with Carine, Chris’s sister.

Q: Sean, what qualities did you find in Emile that made you trust him with this role.

Penn: He’s got a love talent. You used to be able to get some pretty intriguing brooders out of the young generation, or whatever that was. But today you get the clever and the witty and the sexy and the charming, or the this and that… but none of those things happened to be the proper tool for this kid. I needed somebody who had a talent and a mug and a will – and also to photograph somebody going from boy to man, catching somebody on that cusp. So it was all those things that Emile had, and I don’t know another who has that.

Q: Why did you decide to depict the brother-sister bond so strongly despite the fact that he never wrote home during his journey?

Penn: Because I knew it to be so from the letters that he had written her previously from memory, letters that are not copied in either the movie or the book, things that remain private. But it’s not an idle claim that she, in my view, represents what the relationship was. I think that the answer is in the film. I think that she answers it in the narration. But it seems to me that that was the closest I could get to the truth of what that relationship was.

Q: What would you like the audience to take from this movie?

Penn: Whatever they want. Good or bad.

Into the Wild is currently playing in limited release. It begins expanding across the country this Friday, September 28th.