Hollywood loves a good franchise. The movie-going public does too. Horror, action, comedy, sci-fi, western, no genre is safe. And any film, no matter how seemingly stand-alone, conclusive, or inappropriate to sequel, could generate an expansive franchise. They are legion. We are surrounded. But a champion has risen from the rabble to defend us. Me. I have donned my sweats and taken up cinema’s gauntlet. Don’t try this at home. I am a professional.

Let’s be buddies on the Facebookz!

The Franchise: Hellraiser — concerning a supernatural puzzle box (and those humans foolish/unlucky enough to solve it) that opens a doorway to the hellish dimension of Pinhead, the most prominent member of the Cenobites, powerful beings who desire human souls for sadomasochistic experiments. Adapted from Clive Barker’s novella The Hellbound Heart, the franchise spans nine films, from 1987 to 2011.

The Installment: Hellraiser (1987)

The Story:

We begin with Frank Cotton (Sean Chapman), a handsome ne’er-do-well, purchasing a fancy puzzle box from an anonymous Asian man, Gremlins-style. Later, while staying in the attic of his dead parents’ unoccupied home, Frank solves the puzzle box, which summons the Cenobites to whisk him off to a world of “experience beyond limits; pain and pleasure, indivisible.” Not long after, Frank’s nebbish brother Larry (Andrew Robinson) and his bitchy wife Julia (Clare Higgins) move into the house. Julia, we learn, had a steamy affair with Frank before marrying Larry, and has been secretly obsessed with him ever since. When Larry injures himself and bleeds onto the attic floor, Frank is magically reborn, though only partially reformed. Frank plays on Julia’s infatuation and convinces her to bring him victims, so as to make him whole again. Things are going smoothly for the twisted lovers until Larry’s daughter Kirsty (Ashley Laurence) discovers their secret, steals the puzzle box, and has a run-in of her own with the Cenobites.

What Works:

Even great horror movies are often clunky or messy, due to limited budget or limited experience or limited talent or sometimes all of the above. But where they generally succeed (when they succeed) is in the idea department. Horror fans are the most forgiving of serious cinefiles — a forgivingness that tends to be dismissively seen as a lack of taste by those who aren’t into the genre. Some fans are admittedly seeking mindless gore for its own sake, but I think the greater percentage are drawn to the ideas present in these films. In this regard Hellraiser is a phenomenal success. It is a masterstroke of concept and powerful imagery that defiantly steamrolls its many flaws.

Conceptually, the two big successes of Hellraiser – which fairly deserves to share credit with The Hellbound Heart, considering that Barker wrote the novella with the express purpose of turning it into a directing vehicle for himself – are the puzzle box and the Cenobites.

Hellraiser is sort of the zenith or accumulation of Barker’s interests at this time, coming off his seminal Books of Blood collections. And the puzzle box (or Lament Configuration) finds Barker exploring one of his favorite early devices — an object/ritual that opens a doorway or Faustianly binds one to the supernatural. Most similar is his short story “The Inhuman Condition,” in which a knot-loving man untangles an elaborately knotted piece of string only to discover that doing so unleashes a horde of demons. The Hellraiser puzzle box is that idea perfected. There is something wickedly romantic about a puzzle that destroys you if you solve it — it is a timeless, mythic idea. And having Frank seek the puzzle box out, knowing (mostly) what is in store for him, gives the set-up of the film an Icarus by way of Lovecraft flavor. Which makes sense, as Barker has always been a sexier (or pervier) Lovecraft. Herein lies the power and appeal of Hellraiser. Horror in the 80’s featured plenty of sexy ladies, but the films were rarely ever sexy themselves. Conversely, while Hellraiser lacks the typical skinny-dipping scenes and buxom underwear clad co-eds, it has a pervasive sexiness emanating from its core. It may sound goofy, but subconsciously the puzzle box represents this. The puzzle box’s “prize” is simultaneously alluring and horrifying — like the film itself.

The puzzle box may be the subconscious core of the film, but the Cenobites are what you walk away immediately thinking about. The most marvelous thing about the characters is that they aren’t the villains of the film (Frank and Julia are). They aren’t even villains in general. Pinhead tells us that the Cenobites are known to some as angels, and to others as demons, which very succinctly positions them as an amoral force. If you’re into their special brand of sadomasochism and body modification, then they’re probably groovy pals. Even for those who fear them, they are more like repo men than maniacs. You may view them as an adversary if they’re after you, but they’re really just fulfilling their end of a deal. And unlike Freddy or Jason, we learn they can easily be bargained with. There is a rationality to the danger in Hellraiser. The Cenobites have their own code and rules. You have to respect them on some level. They aren’t just popping over to Earth to kill drunk teenagers. Cenobite is an actual word (though it sounds rather stupid and made up), referring to a member of a monastic community. Knowing this contextualizes them in a different way. They believe in something, a higher something, and are more or less indifferent to our world. Oddly enough, it is almost more unsettling that they don’t want to simply kill us for standard villainous reasons (revenge, craziness, etc), but rather to take us/themselves to a transcendent plane of unimaginable sensation (both Barker and Lovecraft love writing about things no one can imagine). Most movie monsters just want to eat you or stab you in the face.

As anyone who has seen his drawings knows, Barker is a skilled artist. So it isn’t a surprise that the imagery of the Cenobites is just as powerful as their schtick. In real life, extreme body modification is captivating because those who partake in it do so honestly — meaning, they aren’t doing it to gross you out. Like any kind of cultural body modifications (from tribal neck elongations down to adorable butterfly tattoos on your ankle), the people who engage in the practice think it makes them look better, or brings them closer to something. Barker has described the Cenobites’ look as “repulsive glamor.” Freddy was disfigured by his enemies. The Cenobites disguised themselves, and presumably they think they look hot. Grotesque sexiness. Kinkiness too. All that leather, and their weapon of choice: hooked chains. Everything about the Cenobites is gold, and anytime they are on screen the movie nails it.

All that said, objectively the biggest single success of Hellraiser is of course Pinhead. Every horror franchise needs a figurehead. Yet Pinhead was never supposed to be that. Not much of a character in Hellbound Heart – the Cenobite leader was The Engineer (more on him later) – he was expanded upon for the film, presumably because his design looked so awesome. Yet on paper he isn’t much more impressive than he was in the book. Boringly named “Lead Cenobite,” he has some cool lines, but is a mostly passive character with only a few scenes. Frank and Julia are the meaty roles here. Yet Pinhead’s design is so mesmerizingly heinous and instantly iconic that his image is fried into your brain pretty much the moment you first see him. And Doug Bradley elevates the character to a level deserving of that image. In Hellbound Heart the character says very little and is described as being somewhat hyper and having a high, girlish voice. It is hard to imagine where this franchise would’ve gone (if it went anywhere) if Barker had kept that take on the character. Bradley makes Pinhead regal, almost stodgy; he has the proper air and rigid posture of a British military officer. His monotone and aloof delivery gives each of his meager number of lines immense power. It also makes his fleeting moments of levity all the better — sort of Dracula meets Spock. It isn’t surprising that Pinhead captivated audiences and immediately became the centerpiece of the advertising and later the franchise itself. He is the runaway hit of the film.

Though Pinhead’s awesomeness tends to overwhelm people’s memories of the film, the A-plot, the Frank and Julia storyline, is nonetheless the marrow of the narrative. And a great one at that. Horror movies about really awful people are always fun to watch, and you sort of root for Frank and Julia in a twisted way — at least as far as wanting to see them further the story by reconstituting Frank. The section of the film where Julia is bringing home sad, average looking men (who all seem to feebly note that they’ve never had a one-night stand before), and bashing their heads in with a hammer so Frank can absorb them, is the most successful portion of the story. I particularly like the farcical moment when Larry has arrived home early and Julia is trying to hide a partially devoured corpse before he reaches the top of the stairs. Julia is a wonderfully detestable character, even more so because she’s so pathetic — it is obvious from the get-go that Frank is playing her to get what he wants. She also has fucking crasy-ass 80’s hair. Frank is an unusual villain. He is the driving force of the film, yet for most of the film’s run-time he is too weak to do anything himself. He is also driven entirely by fear (of getting caught by the Cenobites again), which is a unique motivation for a villain. All the special FX related to Frank are amazing. His rebirth scene – in which a few drops of blood cause Frank’s skeleton to inversely reform out of the floorboards – is one of cinema’s best practical FX set-pieces, right up there with American Werewolf in London and The Thing. And the slow evolution of Frank from that skeleton to an increasingly re-fleshed man is gross and excellent. The look of Frank – skinless, moist deep-red muscles over bone, wearing a suit and leaving blood stains on his collar – is almost as iconic as Pinhead.

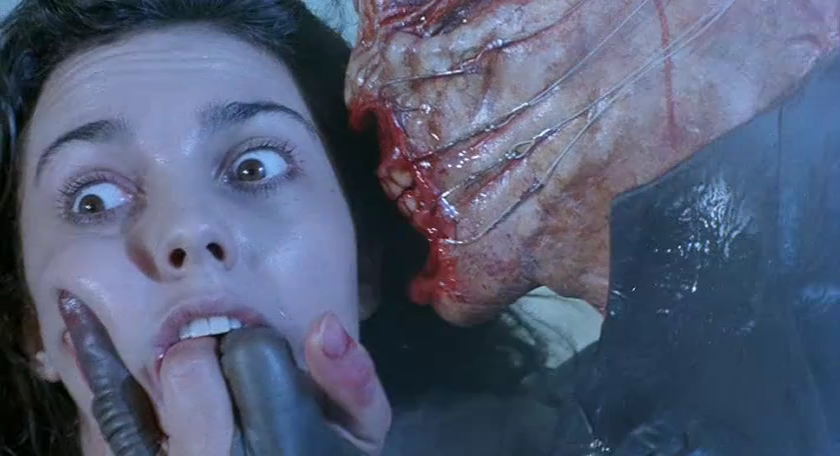

Barker is an expert horror storyteller (duh) and a great visualizer. So the film is littered with indelible images and great gross little bits — like the mysterious homeless man eating live crickets at Kirsty’s pet store, or Frank carving the skin off a rat while watching Larry and Julia in bed, or a tiny heart beating beneath the floor boards. And I have no idea why he does it, but I love that the Teeth Chattering Cenobite’s first move when subduing Kirsty is to jam two of his fingers in her mouth. What a simplistically repulsive thing for a monster to do. Perv.

What Doesn’t Work:

Barker may be a great narrative storyteller and visualizer, but strangely that doesn’t add up to making him a great filmmaker. Hellraiser is a very uneven film and in a sense it works despite itself.

For one thing, the casting is subpar. Doug Bradley is great, but that was something of a lucky accident — Barker let Bradley choose which character he wanted to play, giving him a choice between Lead Cenobite and one of the movers who appear early in the film. Clare Higgins as Julia is the only lead I actually like. The success of Andrew Robinson’s Larry depends on how you read the character, I suppose. Robinson is always smarmy and creepy, and here he is too perfect as the kind of ineffectual and borderline unlikable husband that would drive his wife into his brother’s arms — he is such a little bitch when he cuts himself on a nail that I immediately disconnected with the character. I wanted Julia to betray him. But Julia is a villain. We aren’t supposed to side with her reasoning. Or are we? While aspects of this are interesting for the story, ultimately it is bad news because it lessens the dramatic impact of Larry’s misfortunes in the film. Hell, I wanted something bad to happen to him, and much sooner than it does. The only portion of the film where Robinson seems appropriate is when he is playing Frank (wearing Larry’s skin). Here he is great. And one of three actors to play Frank. Sean Chapman plays human Frank, presumably just cause Barker liked the way he looks, because Oliver Smith plays monster Frank. Smith also dubs over all of Chapman’s dialogue, very noticeably. Smith has a cool voice, but I’m not sure why they didn’t just get one guy to play both versions of Frank and save portions of the film from feeling like an old Italian movie. It’s not like Chapman is impossibly handsome or anything.

Ashley Laurence isn’t terrible as Kirsty, so much as just kinda forgettable. Which isn’t entirely her fault. For the majority of the film, Julia is the central character. And like I said, these sections of the film really work. Then, as the film progresses, Kirsty enters, serving the more typical and wildly less entertaining role of a young horror heroine. This focus shift is the exact sort of thing that works just fine in a book, but generally makes a film feel emotionally nebulous. The film needed either more or less of Kirsty. As is, I didn’t care about the character because I didn’t know much about her. Her few early scenes are wasted on a pointless romantic subplot with the film’s most worthless character, Steve (Robert Hines). Steve serves no point whatsoever and Hines is anti-charming. In his first scene – during a dinner party – when Kirsty says she can’t drink anymore or she won’t be able to stand up, Steve says “So lie down” with a rapey non-flirting smirk. Right in front of her dad! And Larry smiles, like it was charming! In Hellbound Heart Kirsty was a friend of Larry’s, who clearly has some feelings for him. This worked better within the structure of the story. Making Kirsty the daughter and giving her a romantic interest would’ve worked much better if the story had been told from her perspective. But it isn’t. Not until midway through the film.

The nebulous shift over to Kirsty is most acutely felt during the climax, where it forced Barker to make some poor choices. Once Frank, our true villain, is dead, the movie should be over. But this young-daughter version of Kirsty is here to make Hellraiser a little more accessible, so Barker (or someone) clearly felt that the movie needed something more cinematic as a closer. In the book the Cenobites come take Frank and then peace-out, the Engineer handing Kirsty the puzzle box as they leave. In Hellraiser Barker has the Cenobites welsh on their agreement with Kirsty (to let her go if she delivers Frank to them), and try to capture her. A chase ensues. The Engineer does show up, but now Kirsty shoots him with the puzzle box, sending the Cenobites back to their world or whatever. Huh? This ending undoes everything that was cool about the Cenobites, and their code of conduct. Why did they welsh? Why can the puzzle box be turned into a quasi-laser-weapon? Then there is a nonsensical epilogue where Kirsty and Steve try to destroy the puzzle box by throwing it in a fire, but the hobo who ate live crickets in Kirsty’s pet store shows up, grabs the box and transforms into a retarded-looking cow-skull-demon-thing and flies away.

Speaking of retarded-looking things. The FX in Hellraiser are just as uneven as the film itself. Frank and the Cenobites look amazing, but the Engineer (or whatever he’s technically called in the film) is incredibly terrible and cheesy looking. This thing…

And that’s actually a pretty decent pic of it. The two times we see this Pepto Bismol monstrosity completely pulled me out of the film, as we transitioned from fairly realistic horror to a schlocky Corman-esque creature feature. Most of the flesh-ripping FX are oddly subpar too, though those are far more forgivable. But still odd considering the high quality of most of the make-up work. The film also features a bit too much lowgrade hand-animated electrical FX.

The film has a weird flow at times, and some questionable hiccups in its own logic. In the book Kirsty is only able to solve the puzzle box because it has some of Frank’s bloody finger prints on it, allowing her to see the normally invisible seams. Possibly this was still running through Barker’s head, but it is never visualized or spoken of in the film. As is, the puzzle box comes off as incredibly easy to solve. Which destroys a lot of its coolness. Not to mention suspense.

Overall Body Count: 6.

Souls Torn Apart By Cenobites: 1 — though technically they kill Frank twice.

Best Kill: Frank’s second death. After accidentally revealing himself to the Cenobites, Frank is seized by countless chained hooks from every direction. As he makes eye contact with a terrified Kirsty, he licks his lips, then says “Jesus wept,” before being promptly torn apart. It’s awesome.

Best Cenobite That Isn’t Pinhead: I’ve always been partial to the Teeth Chattering Cenobite.

Best Badass Pinhead Line: To Kirsty, as a threat if she deceives them. “We’ll tear your soul apart!”

Best Whimsical Pinhead Line: To Kirsty, when she starts weeping. “No tears please. It is a waste of good suffering.”

Most Unpleasant Moment: Surprisingly, of all the horrible shit that happens in the film, that part that gets me most is the Hitchcockian editing as Larry’s hand keeps jerking closer and closer to a nail that we just know he’s going to tear open the back of his hand on while moving a couch.

Should There Have Been a Sequel: Hell yes. (pun intended)

Up Next: Hellbound: Hellraiser II

previous franchises battled

Critters

Death Wish

Leprechaun

Phantasm

Planet of the Apes

Police Academy

Rambo

Tremors