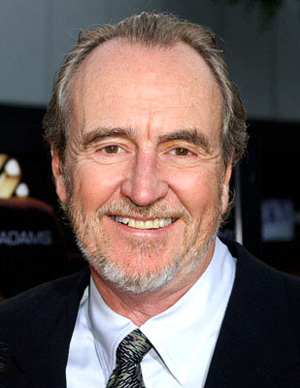

Even legends can fall on hard times. The last few years hadn’t been very kind to Wes Craven, until 2005’s Red Eye reminded people that he was a director who could matter. Over the years he really has mattered – not only has his Nightmare on Elm Street become one of the fixtures of the modern horror imagination, his early films are high points in the 70s exploitation world. Last House on the Left and The Hills Have Eyes have remained justly infamous for their bleak, edgy qualities. They’re the kinds of films that it seemed like Craven himself killed off with his horror-spoof Scream films.

But the genre has proven it won’t die so easily, and Craven is actually working to bring it back. He hand-picked High Tension director Alexandre Aja to helm the remake of his seminal Hills Have Eyes, the movie that introduced the cranium of Michael Berryman to the world at large. It’s a remake that I think is fantastic.

Earlier this week I had a chance to talk with Craven on the phone. He had a lot to say, not just about where he’s been, but where he’s going. In fact his own future – one outside of the confines of the horror genre – is something obviously very much on his mind.

Q: The Hills Have Eyes is a remake of one of your earlier films – does it bother you to compare the two? They’re so different just in the resources Alex had available versus what you had. Is it fair to compare the two films?

Craven: All’s fair in love and war. It doesn’t bother me; certainly it was actually fascinating for me to watch somebody do essentially the same material, although Alex added a great deal of story that wasn’t in the original. Just to watch how somebody’s mind approaches characters and structure and so forth on the same material but very differently.

Q: I’m assuming you’re very happy with what he came up with.

Craven: Absolutely. He made a great film, and very powerful and really fascinating world of the Atomic Village as I call it, is really beautiful and haunting.

Q: He’s part of a new wave of filmmakers who are returning to the stuff that you were doing early on in your career, some really brutal and nasty films. What do you think of the return to more grindhouse elements?

Craven: There’s a certain brutal honesty to it, and perhaps a reaction to Republican strictures right now. Beyond that, I don’t know – I suppose in some ways it’s a tribute and in some way’s it’s a reaction to the post-modern deconstruction of the genre, a return to the roots. It feel appropriate to the fans.

Q: Last House on the Left, if you watched it today, is still disturbing, is still difficult. Are you the same person – could you make a film like that again?

Q: Last House on the Left, if you watched it today, is still disturbing, is still difficult. Are you the same person – could you make a film like that again?

Craven: I don’t think I would want to, at least certainly not that film. It is a very difficult film. I watched it recently when we did commentary – Sean Cunningham and myself – for it, and it remained disturbing. So I don’t think so. I think filmmakers go through arcs of development that make those early films not something you want to go back to. Not sad that you made, or embarrassed of, but it’s part of a whole character arc for the directors.

Q: Where is your arc at now? I know you’ve been working to move beyond the horror genre and you’ve had success in the past year with a suspense film.

Craven: I think there has been, with the popularity of horror, there’s been a broadening awareness of me. I think the fact that the early films are now being considered by adults who were teenagers when they saw it and they liked it then and they’re looking at them with a less prejudiced eye than critics did in the 70s, it makes the whole thing more legit. So that’s interesting.

Myself, I just started to feel constricted after the end of Scream. I felt like it would be interesting to try some different things, and Red Eye was a real pleasure because it had elements of comedy and elements of romance. I was aware that I was a person who didn’t just go to horror films. I have very many interests, and it was fun to do something outside the box for myself. Right now I’m writing a magic show – Macabre Magick – for Las Vegas, for a large theater. I was approached by the man who did the original Riverdance, which is of course very middle-brow, very public. But he wants to do something based on a stage play that was in Dublin by a magician that was quite bloody. I’m just looking to expand myself working off the base I’ve built, but also I think people are starting to realize that I’m a director who can be funny and do things about people in more normal circumstances. To me it’s interesting to do that for a while.

Q: Is the idea that you’re doing a Vegas show as weird to you as it is to me?

Craven: [laughs] Yeah, absolutely. I hope I don’t end up like Wayne Newton with my Vegas show. But if it’s really cutting edge, I think it can be fun.

Q: You’ve become a brand name, with “Wes Craven’s” appearing in front of a lot of films. Is that your seal of approval? How do you control that?

Q: You’ve become a brand name, with “Wes Craven’s” appearing in front of a lot of films. Is that your seal of approval? How do you control that?

Craven: It’s been a tricky thing to control. When we were in our deal with Dimension films, it sort of had been slapped on more by the studio than by myself on projects that might or might not have been the greatest of films. I’m not going to get particular, but I think that was getting a little too sloppy. We’re being very careful about it now, which is one of the reasons we’re doing something we could produce and handle ourselves. With The Hills Have Eyes there was virtually no interference from the studio, only support.

I think it’s good to be a brand name in some ways, and in some ways in the past it’s made it difficult to get material that’s anything away from that, if you know what I mean. But over however many decades, people have gradually begun to realize that the people who make horror films are not monsters and have other sensibilities too. Just like Raimi went on to do something much more popular than his early horror films, and Peter Jackson went on to do something quite different from his early one or two horror films. I think I can, so that’s what I want to do with it. I’m sure on my grave, or in my obituary, it’ll say, ‘He’s still remembered most for creating Freddy Krueger,’ or something like that.

Q: Speaking of your time at Dimension, I have read that it was difficult for you and that there were problems. What did you learn from dealing with the Weinsteins and with Cursed?

Craven: I learned that you can never count on anything. There were times at that studio when we got really fantastic support, like with the Scream films, and then things seem to go awry within the studio. I don’t know whether it was the stress of going through their “divorce” or whatever, but something got all skewed. There was a lot of changing of minds at the last minute, or changing of minds when we were well into a picture – pulling the plug on a picture we were ready to shoot, Pulse, and then pulling the plug twice on Cursed and completely revamping it. That sort of stuff is really difficult, so I guess in some ways I learned of the difficulty of a long term housekeeping with a studio.

The most important thing I learned is that you have to keep working. If something happened that wasn’t quite pleasant, or a film wasn’t what you hoped it would be, you just have to move on. After Cursed I was almost ready to retire and then I did Red Eye and it saved my ass. Even though the two films kind of overlapped, so I was really tapped out. [laughs] I was pretty damn tired after three years on Cursed! But I made a pretty damn good film, I think, and it changed a lot of things.

You have to treat it as something you do as a professional. If art or inspiration creeps in, that’s great, you’re always looking for that, but you keep working and keep honing your chops and hopefully develop a little more.

Q: You said that Fox didn’t give Hills a hard time, but I guess the MPAA did want some stuff cut. In terms of your experience over the years, do you think the MPAA is more permissive or less permissive with what you can get away with?

Q: You said that Fox didn’t give Hills a hard time, but I guess the MPAA did want some stuff cut. In terms of your experience over the years, do you think the MPAA is more permissive or less permissive with what you can get away with?

Craven: I have never been able to figure out any consistency with the MPAA whatsoever. You can make a film yourself that gets censored heavily and then you go to a theater and you see something that you’re astonished got an R. I think the whole way the thing is set up almost prevents consistency. There are almost random groups of people, and the only qualification I think is that they’re parents. Even within one picture you might get a totally different group of people that sees your cut after you’ve tried to follow their notes. So they might have a totally different set of priorities. It’s very, very frustrating. One never knows going in there whether they’re going to cut your film to pieces, or whether they’ll say –

They said on the original Scream, there were two or three submissions where they said we had to cut the entire last scene, in the kitchen. It was too bloody, you can’t have two kids stabbing each other. Then Bob Weinstein called them up and said it’s a spoof, and I swear to God the next day we got an R. Oh, it’s that arbitrary?

There’s a very interesting film that I’ve heard people describe at festivals called This Film Is Not Yet Rated, which is about the MPAA. I’m really anxious to see it because I’m told it blows the lid off that whole fiasco.

Q: I’ve heard that’s a great film. A couple of weeks ago I was talking to Wayne Kramer, who is featured in the movie, and he told me that you can’t plead precedent to them, which is amazing.

Q: I’ve heard that’s a great film. A couple of weeks ago I was talking to Wayne Kramer, who is featured in the movie, and he told me that you can’t plead precedent to them, which is amazing.

Craven: On Deadly Friend we had a scene where a nasty old lady gets her head knocked off with a basketball. The actual scene as it was originally cut was fabulous, she was running around the room like a chicken with its head cut off for ten, fifteen seconds. It was bizarre and wonderful and they cut the shit out of it. So I compiled what we called our “Decapitation Compilation,” all the films that I knew of that had decapitations in them that had an R, and sent it to them. They immediately sent it back saying they just base it on what they feel in the room at the time. And we had like 8 or 10 films in there, like the Omen where the guy gets his head cut off by the sheet of glass, and it didn’t matter to them. There is no precedent you can look at. There is no consistency. And because they’ve been pressured legally they won’t even say anything very specific about what you have to cut – mostly what you get is a note. They’ll tell you, ‘This part of the movie, between footage 300 and 650, is too intense so cut down the intensity.’ You look at them like, that’s what I’m doing, I’m trying to make an intense scene. And they say, ‘Yeah, but it’s too intense and if a child should happen to walk in the theater it might damage him.’ What child? It’s the phantom child! It’s very difficult, especially as a filmmaker in this genre. It’s the last few moments of your making of this particular film and you’re crunched for time and money and suddenly you have to stop what this group of people think, and you have to change it. You’re already in your mix so every change is gruesomely complicated. It goes on and on.

Q: One place where the MPAA can’t control you is Showtime, and I’ve heard that you might be doing an episode in the second season of Masters of Horror. Is this true?

Craven: It’s a possibility. I certainly don’t want to give the idea that I definitely am, because I’m working on a lot of things that are more my own, frankly. It would be nice to go in with that group of guys, all of whom I know, but I’m not sure whether I’ll be able to do that or want to. It’ll depend on a lot of factors. To this point I was working and didn’t have time to do it. I’m not sure it’s the best thing or not, frankly so.

Q: I’ll tell you from a fan point of view, we’d love to see it. And the guys who I’ve talked to who have done it all seemed to have a great time.

Craven: I’m sure of that. Mick is a great guy and he tells me they have complete freedom and so forth. If possible, I’ll do it. If I can find the script.