One of the things that hasn’t been talked about too much in the release of Rango is that it’s ILM’s first animated feature. The look of the film is one of the film’s many highlights – it’s gorgeous –and ILM put their own spin on the CG animated genre. It’s also fair also to say I was excited to talk to Visual Effects Supervisor Tim Alexander and Animation Director Hal Hickel as simply a film fan.

One of the things that hasn’t been talked about too much in the release of Rango is that it’s ILM’s first animated feature. The look of the film is one of the film’s many highlights – it’s gorgeous –and ILM put their own spin on the CG animated genre. It’s also fair also to say I was excited to talk to Visual Effects Supervisor Tim Alexander and Animation Director Hal Hickel as simply a film fan.

Like any good film geek who grew up under the spell of Mr. Spielberg and Mr. Lucas, ILM has always been a constant good to which no work on a shitty movie could in any way dent or ding. One might have issues with The Phantom Menace or- say – Congo, but ILM is a saintly place where people like Ken Ralston, Dennis Murren, Ben Burtt and other nerd legends have become name players to film freaks. These are my people, and I was happy to show them my photographs from being in their Presidio lair, and they were geeking out when I showed them pictures of me holding the original armature for 1933’s King Kong.

Hal Hickel got his start at the Will Vinton studios, and as a former Portland Oregon native, I started by talking about that, until we segued into the movie.

It’s 2011. I say that because Pirates 3 wrapped in 2007, and this is an animated film to which the process tends to be long, when did you guys first come aboard?

HAL HICKEL: We got our first phone calls in the summer of 2007, our first visit with Gore (Verbinski) was in February of 2008, and we really didn’t start building things until August of 2008. There was a whole process of coming to an agreement with the studio, and the budget – that always happens. But that whole summer and spring we had lots of trips to talk to Gore because we were all sure we were going to be making the movie. Then in the fall we really got started in earnest with the lead characters.

Because you’ve spent the last fifteen years or so working in digital effects – but with a number of the characters now all CG – what was the evolutionary leap like to work in animation?

TIM ALEXANDER: I think in terms of the technologies we were using – the detail levels we were going for – it was pretty similar, actually. We knew we needed to hair, so we used our hair pipeline, we knew we wanted to have scattering on the characters, so we used our scattering shaders, and there was definitely a bit of work to do technology-wise in doing something on this kind of scale and this many assets – we’ve never dealt with this many characters, for one. Rigging this many characters, never done that. As well as the number of assets we had to hold, like the town, all the props – there’s like 900 – so there was a lot of work to overcome that hurdle.

The Scale more than the actual thing itself.

ALEXANDER: Yeah.

HICKEL: There were some creative process differences. For instance our layout group at ILM – up until now, the focus of that group is they get live action footage and they match-move the cameras. The match move the shot with the real scene, and they create a virtual camera with a virtual lens that’s got the same camera move and lens so when we create our digital character it gets rendered with the same perspective. That’s the main focus of their group. Well, in this film there is no live action footage. It’s the process of translating the two dimensional storyboards, because this film was put up on story reels as animatics just like any other animated film. And that part of the process was pretty conventional. The Layout group’s job is to translate that two dimensional drawing into a three dimensional scene and that’s a very different job than what our guys were used to doing. Just the idea of working on things as a whole sequence was new. When I would turn a sequence over to animators on a live action film rarely was it possible to get all the animation up and running at once because there were always shots where you were waiting for the miniature elements that had to get pre-comped together with the live action, and only then can put the animated creature in or whatever. Live action’s more of a Frankenstein approach – there’s so many elements coming in from different places – where with an animated film it’s all CG, and it’s always all CG -that doesn’t change – so when I would hand a sequence over to the animators we would say “okay two weeks from now you need to have all you shots at least up to rough blocking, or whatever the date was. And that way we could see the entire scene as rough blocking instead of “well that shot’s not started yet” or “that shots rough, and that shot’s further along. We wanted to get everything up to a certain level, show it to Gore, work over the whole sequence as one piece and get the animation up and then final them and hand them off to the next department. That was a different way of working than normal.

ALEXANDER: I think too that another big difference was psychological. We were involved with the filmmaking process early and so involved with it, and we were doing everything. I think – at least for me and for the crew – it was just being there every day and making big decisions about how the film is going to look and flow – those kinds of things were very different for us. And that’s totally separate from the technology. We were just leveraging stuff we already had, but we had to really figure how we were going to make the whole film. All of a sudden we were directors of photography, and all of a sudden we had all these different jobs that we’d never really done before.

Often with animated films the animators will pitch sequences and ideas. You were working with Gore and John Logan, so was the screenplay a little bit more locked down when you came in or was it flexible?

HICKEL: Well, we were definitely meeting with Gore at the very beginning, so the process of getting the film up on story reels was happening down here (ILM is in San Fransisco, Gore’s offices are in Los Angeles where the interview took place), that went on for about a year, and they really developed the story of the film in traditional animated fashion, which is to say it was a story group, there were drawing as much as they were writing. There was writing, there was drawing and it was working back and forth. Rather than – say – John Logan writing an entire screenplay “Okay, screenplay’s done now start making drawings” it was more the animated film approach, where the story group were contributing lots of ideas, and Jim (James Ward Byrkit) and Gore were with them every day… To be honest I don’t know how John joined that process and contributed a draft, I don’t know. In any case, by the time the film was up on story reels and we were beginning to animate, it was pretty locked down. Stuff did continue to evolve, but not in major ways. It wasn’t like “oh we’re re-writing the third act, hold on!” it was more just tweaking and amplifying or muting certain things.

But then on all levels of the creative process there’s room for input.

HICKEL: Yeah, so – circle back – there was tons of room for contribution from the animators, from all the artists working on the film, but I would say the large framework of the scenes and the movie itself wasn’t constantly fluctuating. So there was tons of room to come up with business or make suggestions “wouldn’t it be funny if he did this?”Or “How about that?” It wasn’t locked down to that degree, and Gore’s very collaborative, so that wasn’t a problem. He’s that great mix of a director who’s collaborative and open, but has a strong vision. There are some guys who are collaborative and open because they don’t have a firm goal in mind, and you end up wandering around a lot, too many cooks in the kitchen and so forth. Gore’s open, but he’s always got a strong drive to something that he’s got locked into his head, which is super helpful.

With this film, is ILM going to start pursuing more animation? Is this the beginning?

ALEXANDER: I hope so, I really loved the experience, I’ve joked that it’s going to be hard to go back to live action now because I enjoyed it so much. Getting back into plate photography and explosions, it’s a whole different mindset. I hope we will pursue more animated films, definitely.

HICKEL: It was a good experience for the company, so as long as the right project comes along at the right time. There’s lots of decisions like “well, we’re already booked fifteen projects, we can’t…” But right project right time, absolutely. One of my many fears going into this at the beginning, because we’re all way out of our comfort zone… I had worked on Toy Story, but I was just an animator, I didn’t have to worry about the big picture, none of us had made an animated feature before – including Gore, Crash (McCreey), Jim, none of us. So we were all well out of our comfort zone. And I worried, I lay awake at night worrying “what if we just completely crash and burn and we take the company down with us?” You know what I mean? Visual effects is not a wide margin business. But that turned out not to be the case, and so I’m hopeful we will be making more animated features.

Was this born out of Gore’s experience with Pirates?

HICKEL : I remember him saying during the crazy circus of shooting two and three back to back “I’d like to do..” but I think he’d been thinking of it even before that. I think he thought it would be a nice thing to do, but in the middle of that this thought crystallized in his mind – cause those films had such insane logistics – “We’ve got a sailing ship that has come down through the Panama canal, and make it over to the Bahamas by this date if there’s no typhoons, and moving whole armies of peoples to the Bahamas and to the Caribbean and back and all this, I think he thought “I could stay local, I’d have this neat little creative world where I don’t have to worry about logistics and things.” I think he learned once he was into it that it would kick his butt in ways he didn’t realize. They all did, actually. But I think going into it that was one of the attractions.

Arm muscles versus leg muscles. (they laugh). It’s funny, I interviewed Jon Knoll for Pirates 3, and he talked about how you will never work on a film bigger than Pirates 3, and I think he’s probably right the way things are changing.

HICKEL: It seems unlikely.

Were there a lot of situations on this film where you kept tinkering with a character’s look?

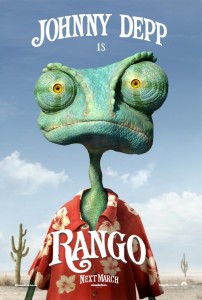

ALEXANDER: Rango – because he’s in pretty much every shot in the film – definitely was a long process in coming up with what he should look like. What his eye bags should look like, what color should they be, how deep the tiles are on his skin, how etc. I mean, Rango was a really big process. Beans (Isla Fisher’s character) was really difficult, it was hard to find her because Gore wanted people to like her but he didn’t want her to be classically pretty. He wanted her to be almost a tomboy – she’s been out there, she’s rough but you’ve got to love her, and that design process was really hard. But then there were other characters that went through no problem. I feel like Priscilla (Abigail Breslin’s character) came quick –

HICKEL: Yeah, she was one straight out of the box. “She’s working, that’s great” but Rango – you look at him – and you think “Oh it’s a green lizard in a red Hawaiian shirt” but if you really look at him in the film there’s so many turquoise-y blues, jade greens in there, plus these warmer yellowy colors in there, and there’s a salmon color on the inside of his lips that comes in. Boy, it was so tricky. It’s not just getting him right and that’s it, you have to put him in a night scene, and then maybe it’s like “oh, that’s weird.”

ALEXANDER: The sequence when Jake (the rattlesnake, played by Bill Nighy) is our most saturated and colorful environment cause it’s that sort of fiery red, sunset sky, and his color went “wooo” on us, so we really had to optimize his color for that sequence

Because Rango is a chameleon there’s a couple of moments where he uses it, did you guys play with that outside of those sequences?

ALEXANDER: Not really, Gore had a really distinct color in mind for Rango, and when he wasn’t that color he would tell us and make sure we got back to that color. And would always depend on what scene you were in and how that color’s perceived in the background, but there was a really distinct green that Gore liked and if it wasn’t there, we made sure we locked into that. So the chameleon color thing we only really used twice.

HICKEL: It’s funny because there are a couple of things about him being a chameleon that we thought we’d end up using a bit more in the film, like his eyes going in different directions. But it just ended up not being organic – we would have had to create a specific gag for it. We kept our eye open for good opportunities, but every time it felt too self-conscious. Every now and then we would separate his eyes a little bit in the timing, but beyond that the opportunity never came up to just hit that. Same thing with the color changing, it was useful, and it fit in the scenes we used it in, but beyond that it felt forced to shoehorn it in again. It didn’t seem necessary. The other thing was the tongue thing that chameleons do, and we actually only had that once, but when we were doing the audio sessions for the saloon sequence there was always a gag where he starts walking around the saloon all tough and he takes a guy’s toothpick, and Johnny said “why doesn’t he use his chameleon tongue?” and so we thought that was brilliant and that made it in, but we had another idea that his tail would get caught in the saloon’s swinging door when he comes through, and we had that in, and at a certain point Gore felt it was interfering with the awkward moment of him coming in

Putting a hat on a hat.

HICKEL: We liked the sound of the doors swinging through after he came in – it just sold the moment a little better. We don’t end up using him as this funny chameleon.

You mentioned The Shakiest Gun of the West as a reference point, watching the film, Chinatown is definitely in there, there’s a lot of Leone and Eastwood, you’ve got some Apocalypse Now, maybe some Star Wars, Raiders of the Lost Ark… was that always part of the game plan, was there anything you were happy to pay homage to?

ALEXANDER: Definitely, one of my favorite is the desert walk sequence where comes through that mirage, and that’s an homage to Lawrence of Arabia. I think there were some conscious ones, definitely the mayor character.

HICKEL: Well, it’s funny that people said to me the canyon chase is similar to the trench run scene in Star Wars and of course there’s an obvious similarity there, but I don’t remember Gore ever even one time referencing that movie to me. Or “these bats have to come in like the tie fighters.” Never uttered. Obviously there’s a similarity there, and I’m sure if you asked him he’d say “oh yeah, it’s a great sequence, why not?” but then other things – like the mayor – is definitely an homage, and the Chinatown stuff is not unintentional. I mean, Once Upon a Time in the West was referenced I don’t know how many times. Or the lighting from There Will Be Blood or things like that. But other things were jut soaked up.

Just growing up in the Lucas/Spielberg era.

HICKEL: Exactly.

I asked Gore about this, you have the actors for reference, but you also have the animators for reference. The animators tend to not be as good at acting.

ALEXANDER: It’s a different process

Was there ever a sense of having to tell them “guys, um, you’re not..”

ALEXANDER: Absolutely

HICKEL: Usually the purpose of the videos the animators shoot has a slightly difference purpose than what an actor might be trying to do on camera. For one thing, the animators tend to be less aware of the camera so they set it up just to record, while actors are very aware of their relationship to the camera, and their good sides and things like that. For the animators it’s a quick working document, or a sketch – generally for kinetics. Sometimes actual acting, what their face is going through, but it’s almost a more mechanical approach than being in the moment. I mean I’m sure there are plenty of animators who are actual actors, they do it as well. For me, when I animate a shot, I’m not an actor, I get a little bit self-conscious in front of the camera, so it’s just a working document. Whereas the stuff we were getting from the recording session… those are actors, they do this for a living. My point is that neither Gore nor I would see the videos the animators would shoot, we would just see the results in the shot, and frequently in the beginning of the process it was a little over amped, or bouncy, we were applying all the same rules about squash and stretch and all those things, we just needed to dampen them down to get the more natural, quiet version of the performances. It was just a learning curve to go through. And the animators just want to make things move.

You’ve talked about the film being dusty and making it dirty, does that then become a new program for animation like Massive, or is that just something you have to apply?

ALEXANDER: It’s both. For the town Dirt, the guy who was the head of the effects department actually created simulation that could almost run at real time, so that any of the technical directors who happened to be rendering the town – they could render a pass with the dust in town, so out of the box you would get dust any where you looked. That was definitely something we could package up and apply to tons of shot. But there are other things like when they’re riding on their road-runners, and you see the dust plumes coming off the back? Those are shot specific, and can takes weeks to pile through, so it was a combination of those two.

And with that our interview came to an end as we geeked out about nerd stuff. Rango opens Friday.